Key facts about the death of Queen Elizabeth I

- Elizabeth I died on 24 March 1603, after an illness seemingly caused by political and personal sorrows.

- Until her last hours, Elizabeth had named no heir to the throne of England.

- Despite this, many had looked to the king of Scotland, James VI, as the best choice of heir.

- Elizabeth supposedly gave her blessing to James VI before her death.

- James I was proclaimed king of England on 24 March 1603 and was notified of it two days later.

People you need to know

- Sir Robert Carey - courtier and son of a first cousin of Elizabeth I.

- Sir Robert Cecil - younger son of Elizabeth I's foremost politician, Lord Burghley (d. 1598), and Secretary of State for England.

- Elizabeth I - queen of England from November 1558 until March 1603.

- Sir John Harington - courtier, author, and godson of Elizabeth I.

- Katherine Howard, countess of Nottingham - sister of Robert Carey and close companion of Elizabeth I.

- James VI and I - king of Scotland from 1567 and of England from 1603. First of the English Stuart kings.

In the early hours of 24 March 1603, on what was then the eve of the new year, Queen Elizabeth I died quietly in her palace at Richmond.  For those living through those hours of her final decline, it was a time of fear as well as of hope. Many statesmen had grown up knowing only her rule, and change was not always something to be welcomed: a new monarch would mean new favourites, new appointments, and, potentially, new enemies. But more than this, there was a deep uncertainty about the state of the kingdom. The Virgin Queen throughout her years had steadfastly refused to name her successor: she had seen the dangers inherent in a named heir, who could become the focus of plots, sedition, and disharmony in the realm, and on paper there was no shortage of pretenders. To the very end, the queen had protected her own position at the expense of a potential future civil war.

For those living through those hours of her final decline, it was a time of fear as well as of hope. Many statesmen had grown up knowing only her rule, and change was not always something to be welcomed: a new monarch would mean new favourites, new appointments, and, potentially, new enemies. But more than this, there was a deep uncertainty about the state of the kingdom. The Virgin Queen throughout her years had steadfastly refused to name her successor: she had seen the dangers inherent in a named heir, who could become the focus of plots, sedition, and disharmony in the realm, and on paper there was no shortage of pretenders. To the very end, the queen had protected her own position at the expense of a potential future civil war.

The ageing queen

The turn of the century showed no hint that Elizabeth was in her final years. She was ageing, of course, but still in excellent health: she could ride for 10 miles at a time, went on progresses – although perhaps not as extensive as they used to be – and in 1601 was recorded as dancing the difficult and energetic galliard for the visiting Italian duke of Bracciano, Virginio Orsini. Her mind as well as her body was still in good shape: in 1597 she had taken great delight in giving a tactless Polish ambassador a sound dressing down, in completely unprepared yet still perfect Latin, while in 1601 she gave her famous ‘Golden Speech’ to grateful members of parliament.

Yet all was not well in the state of England. In February 1601 Elizabeth’s former favourite, the earl of Essex, rose against her, leaving her with no choice but to execute him. The Irish wars were dragging on and although the ‘arch-traitor’ Hugh O’Neill earl of Tyrone, was slowly being brought to heel, Elizabeth chafed at the idea of coming to terms with him. What’s more, the rebellion in Ireland, combined with the on-going war with Spain, was costing a fortune in both money – it was estimated that the cost of the war in Ireland alone was £300,000 per annum – and lives.  This in turn put a strain on the population, and thus on Elizabeth’s relationship with her people. And all around her, people were dying. The former inner circle of confidants and councillors had, by 1602, almost all gone. The earl of Leicester had died in 1588, Francis Walsingham in 1590, Christopher Hatton in 1591, and Lord Burghley in 1598. With the old guard went the carefully constructed balance in the court and the privy council. Clear factions emerged among the young bloods vying for power and favour and, when disappointed, they started to look elsewhere. Despite any talk of the succession being quickly quashed, the old sun was setting, and people had started casting their eyes to the light of a rising sun.

This in turn put a strain on the population, and thus on Elizabeth’s relationship with her people. And all around her, people were dying. The former inner circle of confidants and councillors had, by 1602, almost all gone. The earl of Leicester had died in 1588, Francis Walsingham in 1590, Christopher Hatton in 1591, and Lord Burghley in 1598. With the old guard went the carefully constructed balance in the court and the privy council. Clear factions emerged among the young bloods vying for power and favour and, when disappointed, they started to look elsewhere. Despite any talk of the succession being quickly quashed, the old sun was setting, and people had started casting their eyes to the light of a rising sun.

By December 1602, in the forty-fifth year of Elizabeth’s reign, the toll had started to show on the queen. At Christmas that year, her godson, Sir John Harington, visited her and wrote his impressions in a letter to his wife. ‘Oure deare Queene, my royale godmother, and this state's natural mother, dothe now bear shew of human infirmitie’:

I was not unheedfull to feede her humoure, and reade some verses, whereat she smilede once, and was pleasede to saie; 'When thou doste feele creepinge tyme at thye gate, these fooleries will please thee lesse; I am paste [sic] my relishe for suche matters: thou seeste my bodilie meate dothe not suite me well; I have eaten but one ill tastede cake since yesternighte.’

Terminal decline

Perhaps the final straw was the death of the queen’s close companion, Katherine Howard countess of Nottingham, on 24 February 1603. A close kinswoman of the queen, she had joined the Lady Elizabeth’s household when still a child, and shortly after Elizabeth’s accession she became a maid of honour. For 44 years, Howard had served Elizabeth, gaining ever more in importance as the older generation died. Now, with Howard’s death, Elizabeth lost her last connection to her youth. As one intercepted letter to Venice reported,

The Queen … hath seemed to take her death very heavily, remaining ever since in a deep melancholy, with conceit of her own death, and complaineth of many infirmities suddenly to have overtaken her, as impostumation in her head, aches in her bones, and continued cold in her legs, besides notable decay in judgment and memory, insomuch as she cannot attend to any discourses of government and state … so as none of the Council, but the Secretary, dare come in her presence.

The queen’s condition steadily worsened. She kept to her rooms and refused to go to bed, believing, if she were to do so, that she would die. Instead, she sat on cushions and refused food and the ministrations of her doctors. To add an ominous note, the historian William Camden recorded that it was around this time that she commanded the coronation ring, which she had not removed since her inauguration, ‘be filed off from her Finger, because it was so grown into the Flesh, that it could not be drawn off. Which was taken as a sad Omen, as if it portended that her Marriage with the Kingdome, contracted by that Ring, would now be dissolved.’  Her throat swelled up so she was unable to speak, instead fixing her eyes pensively ‘upon one object many howres togither’, and communicating only occasionally with the use of her hands.

Her throat swelled up so she was unable to speak, instead fixing her eyes pensively ‘upon one object many howres togither’, and communicating only occasionally with the use of her hands.  There was a brief cause for celebration around 11 March, after a ‘defluxion’ in her throat, which initially seemed almost to choke her, was cleared, but the respite was not to last long. It is possible that this torrent of foul matter was triggered by abscesses in her throat and mouth bursting, caused by what Leanda de Lisle has diagnosed as Ludwig’s Angina and not helped by Elizabeth’s sweet tooth and rotting teeth.

There was a brief cause for celebration around 11 March, after a ‘defluxion’ in her throat, which initially seemed almost to choke her, was cleared, but the respite was not to last long. It is possible that this torrent of foul matter was triggered by abscesses in her throat and mouth bursting, caused by what Leanda de Lisle has diagnosed as Ludwig’s Angina and not helped by Elizabeth’s sweet tooth and rotting teeth.  If de Lisle is correct, then in the absence of antibiotics this would almost certainly have proved fatal.

If de Lisle is correct, then in the absence of antibiotics this would almost certainly have proved fatal.

Final days

By 17 March it was becoming clear that the queen would make no permanent recovery, and preparations were made for the transfer of power. The nobility, sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character. , sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character. , sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character. were called to court and the palace guard was doubled; malcontents – especially some notable Catholic recusants – were committed to prison or sent to the Low Countries; the defences of London were strengthened, stockpiles of wheat were checked, and Elizabeth’s jewels were stored for safe-keeping in the Tower; the border areas were put on high alert; and those pretenders resident in England, most notably the English-born cousin of James VI, Arbella Stuart, were put under close watch.

Of course, in retrospect none of this was needed. The machinations of Robert Cecil, secretary of state and the most important man in Elizabeth’s government, ensured there would be a smooth transition. Since the death of the earl of Essex in 1601, Cecil had been conducting a coded correspondence with James VI of Scotland, placing both the king and himself in the most advantageous position possible. By the beginning of 1603 it was being widely acknowledged, and reported, that James was sure of the English crown. Indeed, this news did little to help the queen’s health: Camden records that the French king, Henri IV, warned Elizabeth of conversations between her courtiers and the Scottish king, and Harington lamented that ‘I finde some lesse mindfull of whate they are soone to lose, than of what they may perchance hereafter get.’  Elizabeth, who had successfully avoided talk of the succession for all these years, was now suffering the fate she had feared.

Elizabeth, who had successfully avoided talk of the succession for all these years, was now suffering the fate she had feared.

In the meantime, the grieving earl of Nottingham was called to Richmond to talk the queen into going to bed, to which she eventually consented. Thereafter, it was simply a case of waiting. The queen’s maids tended to her as best they could, and a select few privy councillors waited on her, trying to get a definitive answer to the succession. Their efforts were not helped by Elizabeth’s inability to speak. It was, however, reported that the queen indicated her choice of successor – James VI of Scotland – by raising her hand when his name was mentioned. This, of course, might simply have been broadcast to ease the changeover to someone on whom several members of the privy council had already decided, and reports of different variations of the ‘conversation’ do suggest some discrepancy. But James, despite theoretically being barred from the succession by Henry VIII and by being Scottish rather than English, did appear to be the best choice: he was a kinsman of Elizabeth, he was male and not Spanish, he already had a supply of future heirs, and, importantly, he was of the right religion. Furthermore, it seemed that Elizabeth had favoured him: although she had never announced anything publicly, she had granted him a pension and had not overtly discouraged his hopes.

At about 6pm on Wednesday 23 March John Whitgift, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the queen’s chaplains were called to her. On creaking knees, Whitgift knelt by her bedside,

and examined her first of her faith; and she so punctually answered all his several questions, by lifting up her eyes, and holding up her hand, as it was a comfort to all the beholders. Then the good man told her plainly what she was, and what she was to come to; and though she had been long a great Queen here upon earth, yet shortly she was to yield an account of her stewardship to the King of kings. After this he began to pray, and all that were by did answer him. After he had continued long in prayer, till the old man’s knees were weary, he blessed her, and meant to rise and leave her. The Queen made a sign with her hand. My sister … knowing her meaning, told the bishop the Queen desired he would pray still. He did so for a long half hour after, and then thought to leave her. The second time she made sign to have him continue in prayer. He did so for half an hour more, with earnest cries to God for her soul’s health, which he uttered with that fervency of spirit, as the Queen, to all our sight, much rejoiced thereat, and gave testimony to us all of her Christian and comfortable end. By this time it grew late, and every one departed, all but her women that attended her.

A few hours later, she was dead. She was 69 years old and had been queen for 44 years and four months.

The queen is dead; long live the king!

Within hours of her death, the scramble for the new king’s favour began. The former privy council attempted to control the news, locking down the palace and discussing options, but Sir Robert Carey, kinsman to Elizabeth, made the most of his opportunity.  By the time Cecil read out the proclamation announcing the news, at 10am on Thursday 24 March, Carey was already on his way to Scotland, carrying a sapphire ring that would attest to the truth of his report. In just three days he rode the almost-400 miles to Holyrood in Edinburgh, changing horses when necessary, following the route to Berwick that he had once walked in just 12 twelve days for a £2,000 bet. But perhaps making more haste than speed, at about noon on the Saturday he suffered a nasty fall in Norham, a town on the very border of Scotland. As he states in his memoirs, ‘my horse, with one of his heels, gave me a great blow on the head, that made me shed much blood. It made me so weak, that I was forced to ride a soft pace after, so that the King was newly gone to bed by the time that I knocked at the gate.’

By the time Cecil read out the proclamation announcing the news, at 10am on Thursday 24 March, Carey was already on his way to Scotland, carrying a sapphire ring that would attest to the truth of his report. In just three days he rode the almost-400 miles to Holyrood in Edinburgh, changing horses when necessary, following the route to Berwick that he had once walked in just 12 twelve days for a £2,000 bet. But perhaps making more haste than speed, at about noon on the Saturday he suffered a nasty fall in Norham, a town on the very border of Scotland. As he states in his memoirs, ‘my horse, with one of his heels, gave me a great blow on the head, that made me shed much blood. It made me so weak, that I was forced to ride a soft pace after, so that the King was newly gone to bed by the time that I knocked at the gate.’  A pleased James allowed Carey to kiss his hand before summoning doctors to tend to his bloody guest, and as further reward the following morning swore him in as a gentleman of the bedchamber. Sadly for Carey, James’s wish to honour his own Scottish nobles soon led to Carey’s demotion. Not only was his position reduced to the much less important role of gentleman of the privy chamber, but he also lost his wardenry of the Middle Marches and his estates in North Durham.

A pleased James allowed Carey to kiss his hand before summoning doctors to tend to his bloody guest, and as further reward the following morning swore him in as a gentleman of the bedchamber. Sadly for Carey, James’s wish to honour his own Scottish nobles soon led to Carey’s demotion. Not only was his position reduced to the much less important role of gentleman of the privy chamber, but he also lost his wardenry of the Middle Marches and his estates in North Durham.

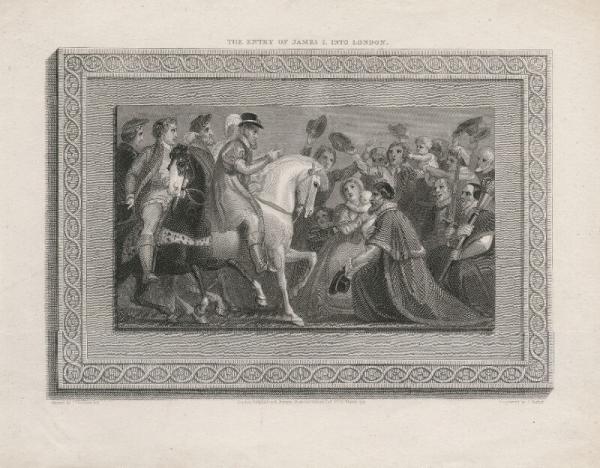

James I set out at a leisurely pace for London on 5 April 1603, his entourage swelling considerably as more English gentlemen came seeking advancement. Petitions, including the famous puritan. . . 1,000-signature Millenary Petition for further reformation of the Church of England, were presented to him, and James handed out so many knighthoods that they fell out of fashion: one account suggests that 906 men were knighted in the first four months of James’s reign alone, and included Thomas Gerard, the brother of the infamous Jesuit John Gerard.  of James I: Historical and Cultural Consequences (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), p. xiii. This was not the only action of the new king to raise eyebrows: when a young cutpurse was caught with a considerable amount of money on him at Newark, James ordered his execution there and then, without access to trial. This might have been the ‘done thing’ in Scotland (and in a very limited number of places in England), but went against almost every precedent in English law. Whatever else this showed, it was clear that England was not just entering a new reign, but a new age. The ‘golden years’ of Elizabeth, the prudent virgin queen who would become almost a goddess in popular memory, were past and, for better or worse, a different style of kingship had begun.

of James I: Historical and Cultural Consequences (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), p. xiii. This was not the only action of the new king to raise eyebrows: when a young cutpurse was caught with a considerable amount of money on him at Newark, James ordered his execution there and then, without access to trial. This might have been the ‘done thing’ in Scotland (and in a very limited number of places in England), but went against almost every precedent in English law. Whatever else this showed, it was clear that England was not just entering a new reign, but a new age. The ‘golden years’ of Elizabeth, the prudent virgin queen who would become almost a goddess in popular memory, were past and, for better or worse, a different style of kingship had begun.

Things to think about

- What caused Elizabeth's death?

- How did reports about Elizabeth's 'good death' affect her posthumous reputation?

- Was the queen right to avoid naming a successor for so long, and were her privy councillors correct in looking elsewhere before her death?

- Was it always likely that James VI of Scotland would have acceded to the English throne, and what could have happened had his way not been prepared?

- How was James's style of kingship different from Elizabeth's (if at all), and how did this affect the course of events during the seventeenth century? How did James's actions affect the later reputation of Elizabeth?

Things to do

- Although Richmond Palace no longer exists, you can still visit the site, part of which is now covered by Trumpeter's House and Sarah's Garden.

- You can visit Elizabeth I's tomb in Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey. Information can be found here.

- James VI was at Holyrood Palace when he discovered he had been declared king of England. You can find information about visiting here.

- Robert Carey rode from London to Edinburgh in about two and a half days (and walked from London to Berwick in twelve). Use Google Maps to trace the best possible route, and marvel at his horsemanship and stamina. How fast would he have been travelling to complete it in that time and how long would it take you to make to same journey?

Further reading

Books on Queen Elizabeth and too numerous to count and vary considerably in quality. However, a good place to start is Helen Castor's biography for the Penguin Monarchs series, Elizabeth I: A Study in Insecurity. For those particularly interested in Elizabeth's later years, try John Guy's Elizabeth: The Forgotten Years.

For the succession crisis and the accession of James I, the best book is probably Susan Doran's Doubtful and Dangerous: The Question of Succession in Late Elizabethan England. For those who want a cheaper, less academic account, try Leanda de Lisle's After Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth and the Coming of King James.