Key facts about 'the puritan. . . threat'

- 'Puritanism Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.' can be taken to mean a lot of things, but it can generally be defined in the seventeenth century as the belief that the Church of England needed further reform.

- Puritans were committed to living in as 'godly' a fashion as possible, following closely the word of the Scriptures and translating that into behaviour and actions.

- They often saw themselves as a people apart, as members of the 'elect' destined to have a place in heaven.

- This separation and their emphasis on further reform could be seen as challenging the structures of society, the Church of England, and the monarchy.

- Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I were all wary of puritans and introduced various policies to curb puritan enthusiasm.

- However, Elizabeth and James had more political sense than Charles and sought a middle way.

- Charles made it obvious that he preferred anti-Calvinist rites and beliefs, and so forced moderate puritans into more extreme positions.

- The way the individual monarchs and their bishops responded to puritans therefore determined the level of threat posed by puritans.

People you need to know

- Charles I - son of James I, and king of England from 1625 until his execution for treason by the Rump of parliament in 1649

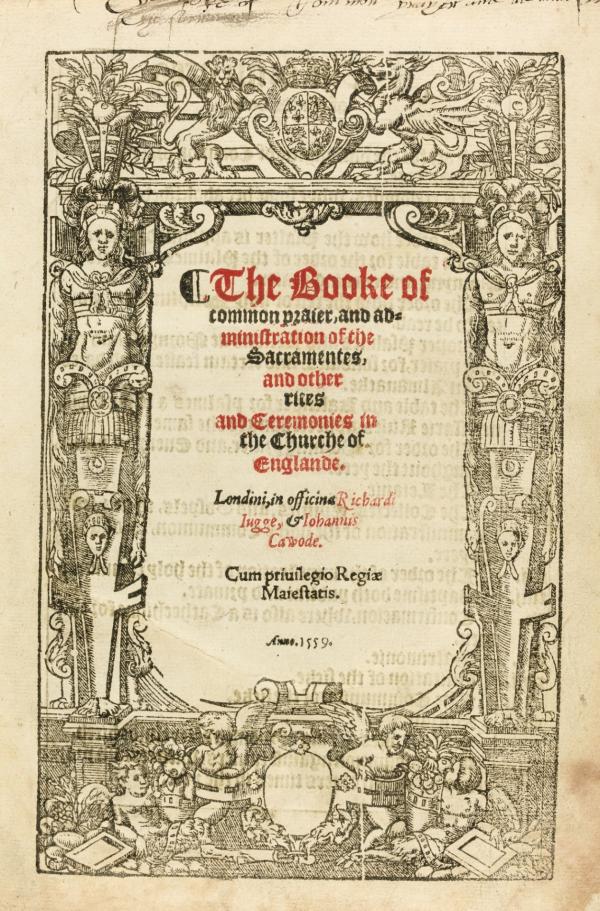

- Elizabeth I - daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and queen of England from 1558 until 1603. Through her religious settlement she reintroduced protestantism to England following the reign of her Catholic half-sister, Mary I.

- James I - king of England from 1603 until 1625, and also James VI of Scotland (from 1567, after the deposition of his Catholic mother, Mary Queen of Scots, by a group of protestant nobles).

- William Laud - Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633 until his execution in 1645. With help from Charles, he introduced a more ritualised and uniform version of Christianity to the Church of England, and questioned elements of Calvinist theory. His version of Christianity is often referred to as Laudianism.

Most historians now agree that there was no puritan . . . threat, either to the Church of England or to the state, in the early seventeenth century, and nor were the civil wars of the middle of the century a puritan revolution. But to those living in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the threat - or the promise - of puritan dominance seemed real. After all, Anglicanism was a new religion, open to attacks from both sides; the power and position of the Church of England seemed precarious and in need of strong defence. A myth was built up and perpetuated by historiography that showed puritans as a dangerous group, seeking to turn the world upside down, to destroy the sacred position of the monarch as head of the church, and to question all divine-right authority. Ultimately, it was this very need to protect the established church, rather than either Catholicism or puritanism Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed., that was its greatest threat. It was the fears of its most vehement supporters that challenged the church’s stability in the short-term, and which turned potential allies into enemies.

. . . threat, either to the Church of England or to the state, in the early seventeenth century, and nor were the civil wars of the middle of the century a puritan revolution. But to those living in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the threat - or the promise - of puritan dominance seemed real. After all, Anglicanism was a new religion, open to attacks from both sides; the power and position of the Church of England seemed precarious and in need of strong defence. A myth was built up and perpetuated by historiography that showed puritans as a dangerous group, seeking to turn the world upside down, to destroy the sacred position of the monarch as head of the church, and to question all divine-right authority. Ultimately, it was this very need to protect the established church, rather than either Catholicism or puritanism Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed., that was its greatest threat. It was the fears of its most vehement supporters that challenged the church’s stability in the short-term, and which turned potential allies into enemies.

Inside or outside? Puritans and the established church

Puritanism was, and is, a nebulous concept. At its most restrictive, it applies to those with reformist views who sat outside the established church. But most puritans chose to reform the church from within, and it was only in the 1630s, when further reformation had failed, that more groups separated. Despite this, investigators saw sectarianism everywhere. Groups meeting to discuss a sermon were considered dangerous conventicles, and pamphlets listed the range of social as well as religious norms broken by separatists. But puritanism was wider than the nonconforming sects, and so should its definition be. Although disagreeing on many points, and changing over time, as a group puritans were fervent in their beliefs, heavily reliant on scripture, committed to further reformation and translating the word of God into the actions and behaviour of everyday life. It is this extremity of belief, and this inner certainty, that separated puritans from their contemporaries, and it is this definition that will be used here.

General puritan commitment to the church contributed to its stability, helping to fortify it against the perceived threat of Roman Catholicism. At the start of Elizabeth I’s reign, Marian exiles flocked back to England, with many taking positions in the new church despite their reservations over the nature of the compromise it represented. For these former exiles, the conservatism of the Elizabethan regime was a concern, as it encouraged the retention of vestments. . . . . and rites that, to those used to continental practice, smacked of popery. John Jewel wrote to the continental divine Peter Martyr ‘that it is idly and scurrilously said … that as heretofore Christ was cast out by his enemies, so he is now kept out by his friends.’ Martyr, for his part, urged the returned exiles ‘not to withdraw yourself from the function offered you’, for 'if you sit at the helm of the church, there is a hope that many things may be corrected’.

Martyr, for his part, urged the returned exiles ‘not to withdraw yourself from the function offered you’, for 'if you sit at the helm of the church, there is a hope that many things may be corrected’. Disagreement over adiaphora and the remnants of ‘popishness’ could destabilise the church, as evidenced by the Vestiarian Controversy, but it also contributed to the via media that was to characterise it. The appointment of moderate puritan bishops continued into James I’s reign, to the point where, in Nicholas Tyacke’s opinion, the assimilation of puritanism had been so successful that ‘society [was] steeped in Calvinist theology’.

Disagreement over adiaphora and the remnants of ‘popishness’ could destabilise the church, as evidenced by the Vestiarian Controversy, but it also contributed to the via media that was to characterise it. The appointment of moderate puritan bishops continued into James I’s reign, to the point where, in Nicholas Tyacke’s opinion, the assimilation of puritanism had been so successful that ‘society [was] steeped in Calvinist theology’. There is little sense, then, in declaring a puritan threat to the Church of England, when many moderate puritans were working for it. Furthermore, even the ‘hotter sort’, upon entering the episcopacy, cooled when confronted with the difficulties of church governance and finance, and their own hopes of career progression.

There is little sense, then, in declaring a puritan threat to the Church of England, when many moderate puritans were working for it. Furthermore, even the ‘hotter sort’, upon entering the episcopacy, cooled when confronted with the difficulties of church governance and finance, and their own hopes of career progression.

Presbyterianism

But those puritans not dealing with political realities were frustrated by the lack of further reform, and therefore attacked the root of their disappointment: the episcopacy. These presbyterian attacks in the first half of Elizabeth’s reign and the fate of episcopalian governance in the 1640s have been used by some to show not just the continuance, but the escalation, of puritan ‘opposition’. Under Elizabeth, the Archbishop of York Edwin Sandys wrote that bishops were considered, in Patrick Collinson’s phrase, ‘excrementum mundi’, while others observed that many ‘minds are entirely set against the bishops; for they scarcely say anything respecting them but what is painted in the blackest colours, and savours of the most perfect hatred.’ Criticism gained support because it tapped into a traditional anticlericalism matters. matters. matters. matters. matters. with a much wider reach than the core of puritan idealists, and because it used witty and satirical propaganda to highlight real problems.

Criticism gained support because it tapped into a traditional anticlericalism matters. matters. matters. matters. matters. with a much wider reach than the core of puritan idealists, and because it used witty and satirical propaganda to highlight real problems.

Yet there was no clear continuation of presbyterianism between 1590 and 1625, although minor tremors – such as the Millenary Petition – occurred. Some have argued that the pamphleteers had gone too far: their vitriol was too much for the moderates who had previously been sympathetic. But in large part it is thanks to sound management, and the removal of criticism by addressing its causes. Under James, the education and quality of the clergy improved, attempts were made to tackle pluralism and non-residence, and a light-touch approach to the enforcement of the canons enabled the puritan clergy to work within the church, with conformity encouraged rather than demanded. Even as late as 1629, some members of parliament were willing to grant that there were a few ‘among our Bishops such as are fit to be made examples for all Ages, who shine in virtue, and are firm for our Religion’.

It was not until the ascent of anti-Calvinism (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith alone that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). , provoked in part by the fear of a puritan fifth column, that presbyterianism again became a problem. But this presbyterianism was a reflection of deeper anxieties over the religious direction of the church and state. Anti-Calvinism had developed from the concern of some within the church that reform had gone too far, from questioning Calvinist doctrines such as double predestination

that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). , provoked in part by the fear of a puritan fifth column, that presbyterianism again became a problem. But this presbyterianism was a reflection of deeper anxieties over the religious direction of the church and state. Anti-Calvinism had developed from the concern of some within the church that reform had gone too far, from questioning Calvinist doctrines such as double predestination that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. , and from belief in piety through expression, ceremonialism, and beauty. This supposedly embattled minority, which has variously been termed ‘Arminian’ and ‘Laudian’, carried their persecution complex forward and into power under Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud and Charles I. As the political climate changed in the 1630s, reluctantly-conforming Calvinist clergy were removed from their positions and turned into opponents. Laud’s dogged insistence ‘that the calling of bishops is jure divino, by divine right’, and that ‘in all ages, in all places, the Church of Christ was governed by bishops, and lay elders never heard of till Calvin’s new-fangled device at Geneva’, was hardly designed to calm his opponents.

that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. , and from belief in piety through expression, ceremonialism, and beauty. This supposedly embattled minority, which has variously been termed ‘Arminian’ and ‘Laudian’, carried their persecution complex forward and into power under Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud and Charles I. As the political climate changed in the 1630s, reluctantly-conforming Calvinist clergy were removed from their positions and turned into opponents. Laud’s dogged insistence ‘that the calling of bishops is jure divino, by divine right’, and that ‘in all ages, in all places, the Church of Christ was governed by bishops, and lay elders never heard of till Calvin’s new-fangled device at Geneva’, was hardly designed to calm his opponents. In fact, it did the opposite: those whom he was attacking in this instance, William Prynne, John Bastwick, and Henry Burton, had originally accepted the Elizabethan settlement, but had become more and more worried by the direction the church was taking under Charles and Laud. Since the founding of the Church of England, puritanism as a potential threat had been weakened by divisions on everything from doctrine to forms of worship and levels of conformity. Now, it was united in its fight against the enemy within.

In fact, it did the opposite: those whom he was attacking in this instance, William Prynne, John Bastwick, and Henry Burton, had originally accepted the Elizabethan settlement, but had become more and more worried by the direction the church was taking under Charles and Laud. Since the founding of the Church of England, puritanism as a potential threat had been weakened by divisions on everything from doctrine to forms of worship and levels of conformity. Now, it was united in its fight against the enemy within.

The role of the monarch

The episcopacy was only one strand in the governance of the Church of England; the other was its supreme governor, the monarch. The church was therefore intricately linked with the state, and both were based on notions of hierarchy and obedience. To question the divine right of one, was to question the divine right of the other: as James, who had spent his time as Scottish king trying to restore the episcopacy, blurted: ‘no bishop, no king’. No wonder, then, that Elizabeth, James, and Charles were all distrustful of puritanism. Elizabeth noted ‘the fanatical humour of ... the Puritan’, and James thought it promoted ‘unprofitable, unsound, seditious and dangerous doctrines, to the scandal of the Church and disquiet of the state and present government’.

No wonder, then, that Elizabeth, James, and Charles were all distrustful of puritanism. Elizabeth noted ‘the fanatical humour of ... the Puritan’, and James thought it promoted ‘unprofitable, unsound, seditious and dangerous doctrines, to the scandal of the Church and disquiet of the state and present government’. Charles, in a proclamation parliament had originally hoped would be anti-Arminian in nature, declared ‘His utter dislike to all those, who … adventure to stirre or move any new Opinions … differing from the sound and Orthodoxall grounds of the true Religion, sincerely professed, and happily established in the Church of England’.

Charles, in a proclamation parliament had originally hoped would be anti-Arminian in nature, declared ‘His utter dislike to all those, who … adventure to stirre or move any new Opinions … differing from the sound and Orthodoxall grounds of the true Religion, sincerely professed, and happily established in the Church of England’. for the establishing of the Peace and Quiet of the Church of England', 14 June 1626, in James F. Larkin (ed.), Stuart royal proclamations. Vol. 2, Royal proclamations of King Charles I, 1625-1646 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1983), pp. 91-3. His true intent was clear when it was shortly afterwards used to prevent Calvinist debates at Cambridge University.

for the establishing of the Peace and Quiet of the Church of England', 14 June 1626, in James F. Larkin (ed.), Stuart royal proclamations. Vol. 2, Royal proclamations of King Charles I, 1625-1646 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1983), pp. 91-3. His true intent was clear when it was shortly afterwards used to prevent Calvinist debates at Cambridge University.

In a world where uniformity of religion expressed unity of state, doctrinal disputes, often preached or published in pamphlets, threatened dissension. The extra-legal ‘voluntary religion’ – the preaching, psalm-singing, fasting, household prayers, and sermon repetition favoured by puritans – theoretically opened the way for schism, and for the ill-informed masses to question government. Disharmony in religion could also provoke disharmony in the community. Richard Bancroft complained about the self-satisfied elect, who ‘condemn all others for papists’. What’s more, each monarch – Elizabeth, James, and Charles – was fiercely protective of their prerogative. When Archbishop Grindal wrote to Elizabeth that he would ‘choose rather to offend your earthly majesty, than to offend the heavenly majesty of God’, he touched a nerve.

What’s more, each monarch – Elizabeth, James, and Charles – was fiercely protective of their prerogative. When Archbishop Grindal wrote to Elizabeth that he would ‘choose rather to offend your earthly majesty, than to offend the heavenly majesty of God’, he touched a nerve. Elizabeth ‘was not prepared to tolerate either a pope of Rome or a pope who had learnt his business in Geneva.’

Elizabeth ‘was not prepared to tolerate either a pope of Rome or a pope who had learnt his business in Geneva.’ The Thirty-Nine Articles, the prohibition on prophesyings, and the Act to Retain the Queen’s Subjects in Obedience all sought to limit the perceived threat of puritanism. James considered opposition to the match between Charles and the Spanish Infanta, and thus to his desire to be Rex Pacificus, as a puritan infringement on his prerogative. Foreshadowing his son, he turned to the anti-Calvinists for support, and released his Directions to Preachers banning puritan ‘ignorant meddling with civil matters’, and preaching ‘in any popular auditory the deep points of predestination, election, reprobation, or of the universality, efficacy, resistibility or irresistibility, of God’s grace’.

The Thirty-Nine Articles, the prohibition on prophesyings, and the Act to Retain the Queen’s Subjects in Obedience all sought to limit the perceived threat of puritanism. James considered opposition to the match between Charles and the Spanish Infanta, and thus to his desire to be Rex Pacificus, as a puritan infringement on his prerogative. Foreshadowing his son, he turned to the anti-Calvinists for support, and released his Directions to Preachers banning puritan ‘ignorant meddling with civil matters’, and preaching ‘in any popular auditory the deep points of predestination, election, reprobation, or of the universality, efficacy, resistibility or irresistibility, of God’s grace’. Even before this, his promotion of sports on the Sabbath and the development of the 1604 canons, to which he ordered subscription, ensured that the extremes of Calvinism were kept in check.

Even before this, his promotion of sports on the Sabbath and the development of the 1604 canons, to which he ordered subscription, ensured that the extremes of Calvinism were kept in check.

Harsh though these measures might be – James was accused of depriving 300 pastors for their refusal to subscribe to the canons – their bark was worse than their bite. The show of conformity, rather than its essence, is what mattered to James and his predecessor. Elizabeth never formally approved Matthew Parker’s Advertisements of 1565, and the Thirty-Nine articles allowed room for a wide interpretation. James listened and responded to puritan complaints at the Hampton Court Conference, including commissioning a new translation of the Bible, altering some of the liturgical language, and attempting to improve the quality of the ministry. Nor did he enforce the canons in a sustained way: the 300 deprivations were closer to 80, and most were in the years immediately following their introduction. Both monarchs could therefore be seen as godly princes, allowing potential critics to view them in a favourable light. It gave moderate puritans the chance to stay within the church, rather than forcing them to work outside it, and divided what could otherwise have been a much more united – and therefore dangerous – puritan front.

and the Thirty-Nine articles allowed room for a wide interpretation. James listened and responded to puritan complaints at the Hampton Court Conference, including commissioning a new translation of the Bible, altering some of the liturgical language, and attempting to improve the quality of the ministry. Nor did he enforce the canons in a sustained way: the 300 deprivations were closer to 80, and most were in the years immediately following their introduction. Both monarchs could therefore be seen as godly princes, allowing potential critics to view them in a favourable light. It gave moderate puritans the chance to stay within the church, rather than forcing them to work outside it, and divided what could otherwise have been a much more united – and therefore dangerous – puritan front.

Charles, it could be argued, did not go much further than his father in promoting the agreed doctrine of the church: his Book of Sports, for example, was a reiteration of James’ 1618 Declaration of Sports. Like his father, he too saw the danger to the people, church, and state in Sabbatarianism. But, unlike his father, he enforced the 1604 canons to the letter, as he likewise did with the Thirty-Nine Articles, demanding subscription to them ‘in the literal and grammatical sense.’ Encouraged, as it was believed, by his Catholic wife and the anti-Calvinists at court, he emphasised ritual and show. But to many, the vestments and practices he insisted upon – such as the position of the communion table – felt like an encroachment of Catholic values into the English church. The puritan faith in the faith of their king was shaken.

Encouraged, as it was believed, by his Catholic wife and the anti-Calvinists at court, he emphasised ritual and show. But to many, the vestments and practices he insisted upon – such as the position of the communion table – felt like an encroachment of Catholic values into the English church. The puritan faith in the faith of their king was shaken.

Tyacke overstated the Calvinism of the English church. Elizabeth and James had succeeded in creating the appearance of unity, but it was the unity of a middle way, a compromise between preaching and ceremonial, double predestination and the mercy of God. Since at least the 1590s, anti-Calvinism had existed within the church, but tensions between them had been well managed. Both sides were elevated to positions of power and had supporters within the privy council, ensuring balance between the parties. But from 1625, anti-Calvinists dominated episcopal appointments and promotions, holding four of the five key sees by 1633, and all of the clerical positions at court. ‘Arminianism’ wasn’t an innovation; it could even be argued that James favoured it towards the end of his life. But under Charles anti-Calvinism triumphed, and when those on the inside suddenly found themselves on the outside, puritanism became a threat to the church. The abrupt change in the actual, rather than theoretical, practice of the church and its governance made opponents of even moderate Calvinists. Historians such as Roger Lockyer have argued that Charles’s anti-Calvinism was not as extreme as commonly believed and instead point to Laud as ‘the greatest calamity ever visited upon the English Church’. But it was Charles, stubborn to the point of death, who oversaw the direction of the church and the appointment of favourites, and he who must take ultimate responsibility.

But it was Charles, stubborn to the point of death, who oversaw the direction of the church and the appointment of favourites, and he who must take ultimate responsibility.

Charles was not a good politician. Perhaps ‘more cleric than king’, he stood firm and favoured one side. Elizabeth carried her way with a firm hand and a gracious smile; James with a keen political awareness and a smooth tongue; Charles with a stamped foot and a sullen frown. By declaring for anti-Calvinism, Charles turned all Calvinists, no matter of what persuasion, into the enemy. The balance, so carefully constructed by his predecessors, crumbled and, when tied to problems of finance and statecraft, the Church of England became just as unstable as the rest of Charles's government. Anti-Calvinism could not have thrived in a political sense, or within the episcopacy, if Charles had not allowed it to. Neither the puritans nor Laud were responsible for the fate of the Church in the run up to the civil wars. Like so much else, the religious buck has to stop with Charles.

Elizabeth carried her way with a firm hand and a gracious smile; James with a keen political awareness and a smooth tongue; Charles with a stamped foot and a sullen frown. By declaring for anti-Calvinism, Charles turned all Calvinists, no matter of what persuasion, into the enemy. The balance, so carefully constructed by his predecessors, crumbled and, when tied to problems of finance and statecraft, the Church of England became just as unstable as the rest of Charles's government. Anti-Calvinism could not have thrived in a political sense, or within the episcopacy, if Charles had not allowed it to. Neither the puritans nor Laud were responsible for the fate of the Church in the run up to the civil wars. Like so much else, the religious buck has to stop with Charles.

Things to think about

- Was Nicholas Tyacke correct in emphasising the Calvinism of the Church of England?

- What was the level of ongoing puritan opposition to the established church and the government?

- How much of a problem did Laud present to the Church of England?

- How much did religious differences in Britain reflect, or were influenced by, religious differences in Europe?

- How successful were Elizabeth, James, and Charles in managing the puritan threat?

- How responsible was Charles for increasing the puritan threat?

Things to do

- Church architecture has been through many changes and upheavals since the seventeenth century. However, if you visit a number of churches, you will begin to see slight differences in their building styles and liturgical fittings. See if you can spot which churches and their fittings were more 'Catholic' and which were more 'Calvinist'.

- The Theological Commons provided by Princeton has a huge collection of online theological texts that you can access. They can be found here.

- Popular opinion was often expressed through 'libels' - satirical poems, jokes, and statements. A good cross-section of libels relating to this period, and to religion, can be found at Early Stuart Libels.

Further reading

There is a vast body of literature relating to puritanism in the early modern period, much of it reasonably weighty. However, within the academic books there are some that are essential reading for a thorough understanding of the subject. These include Patrick Collinson's The Reformation, and The Religion of Protestants: The Church in English Society 1559-1625, Alexandra Walsham's Charitable Hatred: Tolerance and Intolerance in England, 1500–1700, and Nicholas Tyacke's Aspects of English Protestantism, c. 1530-1700 and Anti-Calvinists: The Rise of English Arminianism c. 1590-1640.

For a more general understanding of the time, Roger Lockyer's The Early Stuarts: A Political History of England 1603-1642 is a good place to start.