Key facts about late Tudor and early Stuart parliaments

- Many historians have traced the causes of the Civil War to parliaments behaviour under Elizabeth I and James I

- Even before Charles I, parliaments could cause problems for their monarchs

- Particular flash points were taxation and religion

- Parliament was concerned to protect its liberties, especially its freedom of speech

- Monarchs were equally concerned to protect their prerogative: their right to determine law and direct parliament

- The monarch needed considerable skill, and good privy councillors - who often sat in parliament - to manage parliament

- Elizabeth I was much better at managing parliament than her successors

- James I and Charles I brought a new style of monarchy and a belief in the divine right of kings to England

- James had the skills to adapt his style to that of the English, but Charles refused to go against his beliefs

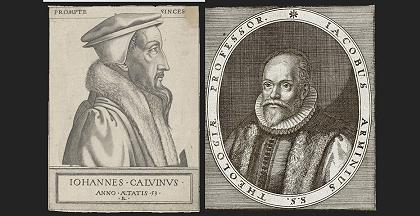

People you need to know

- Charles I - second son of James I, who reigned from 1625 until his execution on the orders of the Rump Parliament in 1649.

- Elizabeth I - last of the Tudor dynasty, who reigned from 1558 until 1603, and who died childless.

- James I - and VI of Scotland, first of the Stuart dynasty in England, who reigned from 1603 until 1625.

- William Laud - bishop and later archbishop of Canterbury under Charles I, who favoured the episcopacy and 'Popish' ritual elements of religious practice.

- Richard Montagu - cleric and prelate who was known for his controversial religious writings in the 1620s.

- John Pym - parliamentarian and leader of the Long Parliament, prominent in his criticism of Charles I.

- George Villiers - first duke of Buckingham, favourite of James and Charles, murdered in 1628.

- Peter Wentworth - outspoken member of parliament during the reign of Elizabeth, who eventually died in prison in 1597.

- Thomas Wentworth - first earl of Strafford and lord lieutenant of Ireland, who was impeached and executed in 1641, much to Charles' chagrin.

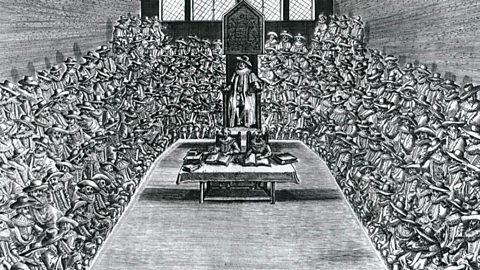

Early modern political theory held that the king-in-parliament was supreme. The king, through his prerogative, directed the law and summoned and dissolved parliament, and parliament, protected by its privileges and liberties, gave consent, supply, and advice. But by 1642, king and parliament were at war. The causes of this breakdown have attracted some of the most interesting, and controversial, debates in recent scholarship. Explanations are numerous, but they all must, at some point, consider the role of parliament. That by the early 1640s parliament’s relationship with the king had become so oppositional it was unworkable is obvious: the Grand Remonstrance provides clear evidence that parliament was no longer willing to work with the king. What is less obvious is how it came to be so: had there been a ‘high road to civil war’, evident in the increasingly adversarial parliaments of Elizabeth I and James I, and the development of a formal counterweight to government? Or were the relationships between the monarchs and their parliaments more amenable; was the collapse of relations the result of a series of unfortunate events and personality clashes?

evident in the increasingly adversarial parliaments of Elizabeth I and James I, and the development of a formal counterweight to government? Or were the relationships between the monarchs and their parliaments more amenable; was the collapse of relations the result of a series of unfortunate events and personality clashes?

Parliamentary problems

Every parliament between 1559 and 1629 opposed certain policies or pushed, against the monarch’s wishes, for certain outcomes. Across the three monarchs, similar themes of contention in religion and finance emerged, but there was also underlying tension between the royal prerogative and the liberties of parliament. Under a knowledgeable, experienced, and emotionally-aware monarch, balance was maintained, but under an inadequate monarch, such as Charles, more serious conflict emerged.

A 'Puritan Choir'?

The Whiggish notion of a ‘puritan revolution’ is, on the surface, convincing. Propounded by the likes of J.E. Neale, the theory holds that parliament, led by a ‘puritan choir’ became more aggressive throughout the reigns of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts, developing an organised programme of reform and pushing the boundaries of its liberties. There is no denying religious conflict existed. In 1566, 1571, 1576, 1581, 1584, 1587, and 1597, elements of the Commons moved to change church practice, often in direct defiance of Elizabeth’s command. Time and again she commanded parliament to ‘not…so much as once meddle with any such matters or causes of religion’. And time and again, parliament challenged her. When William Strickland was sequestered in 1571 for introducing a prayer book bill, the Commons argued ‘that neither in regard of the Country, which was not to be wronged, nor for the Liberty of the House, which was not to be infringed, we should permit him to be detained from us’.

And time and again, parliament challenged her. When William Strickland was sequestered in 1571 for introducing a prayer book bill, the Commons argued ‘that neither in regard of the Country, which was not to be wronged, nor for the Liberty of the House, which was not to be infringed, we should permit him to be detained from us’.

Yet under Elizabeth, conflict wasn’t unmanageable. Partially, this was because reforms were ‘a collaborative exercise between Councillors, bishops and other members of the governing class in Parliament’. Elizabeth was also determined to prevent religious differences turning into organised opposition. She knew when to admit defeat – Strickland was allowed back into the House – and how to turn grievances into positive outcomes. Nor did she allow dispute to become personal, unlike Charles. Christopher Yelverton, a puritan supporter of Strickland, became speaker of the Commons, and the radical Anthony Cope, who’d been arrested in 1587, was knighted. James, too, ‘knew when to yield, and when to stand firm; when to enforce the rules, and when to bend them’. He was so successful that John Pym considered him one of the ‘Fathers of the Church’,

Elizabeth was also determined to prevent religious differences turning into organised opposition. She knew when to admit defeat – Strickland was allowed back into the House – and how to turn grievances into positive outcomes. Nor did she allow dispute to become personal, unlike Charles. Christopher Yelverton, a puritan supporter of Strickland, became speaker of the Commons, and the radical Anthony Cope, who’d been arrested in 1587, was knighted. James, too, ‘knew when to yield, and when to stand firm; when to enforce the rules, and when to bend them’. He was so successful that John Pym considered him one of the ‘Fathers of the Church’, and the fact that the annals of parliament don’t contain more reference to religious grievances in his reign proves his skill.

and the fact that the annals of parliament don’t contain more reference to religious grievances in his reign proves his skill.

Although Charles was willing to give ground on minor points, his evident distrust of puritanism, and the appointments he made to the episcopacy set him against parliament. When the Commons raised concerns over Laud’s ‘Arminian party’ of bishops supporting the controversial cleric Richard Montagu, Charles made Montagu his chaplain, ‘whereat the Commons seemed to be much displeased.’ In 1628 Charles appointed him bishop of Chichester, and in 1633 made Laud archbishop of Canterbury. The parliamentary push for religious reform between 1559 and 1629 didn’t change. The only thing that changed was the monarch: religious disputes in the reign of Charles were more oppositional because he was more oppositional. Charles’ predecessors kept the reformist zeal in check by their willingness to walk a middle line and their refusal to take sides; Charles failed because he favoured, according to a vocal minority in parliament, the wrong side.

In 1628 Charles appointed him bishop of Chichester, and in 1633 made Laud archbishop of Canterbury. The parliamentary push for religious reform between 1559 and 1629 didn’t change. The only thing that changed was the monarch: religious disputes in the reign of Charles were more oppositional because he was more oppositional. Charles’ predecessors kept the reformist zeal in check by their willingness to walk a middle line and their refusal to take sides; Charles failed because he favoured, according to a vocal minority in parliament, the wrong side.

Financial wrangling

Financially, parliamentary opposition focused on two areas: redress before supply, and prerogative finance. According to Michael Graves, at no point in Elizabeth’s reign did the Commons ‘attempt to take political advantage of its initiating role by making a tax grant conditional upon prior redress of grievances.’ However, in 1571, Robert Bell stated that ‘if remedy were provided then would the subsidy be paid willingly’,

However, in 1571, Robert Bell stated that ‘if remedy were provided then would the subsidy be paid willingly’, and supply was used to influence policy. In the draft preamble to the 1566 subsidy bill, parliament – working with the privy council – held Elizabeth to her promise to marry. Although Elizabeth’s fury was enough to change the preamble, she in turn remitted a portion of the supply. By the 1620s, supply was almost always conditional upon prior redress. In 1626 it was dependent upon the removal of Buckingham, and acceptance of the Petition of Right was a necessary step to obtain supply in 1628.

and supply was used to influence policy. In the draft preamble to the 1566 subsidy bill, parliament – working with the privy council – held Elizabeth to her promise to marry. Although Elizabeth’s fury was enough to change the preamble, she in turn remitted a portion of the supply. By the 1620s, supply was almost always conditional upon prior redress. In 1626 it was dependent upon the removal of Buckingham, and acceptance of the Petition of Right was a necessary step to obtain supply in 1628.

An unwillingness to grant taxation was not a deliberate attempt by parliament to wrest power from the monarch, but reaction to a changing economic climate. By the start of the seventeenth century, with inflation soaring and income from lands and taxes falling, extraordinary revenues were needed to pay for ordinary expenses. The more economic issues bit, the more the monarch requested, and the more concerned parliament became. On average, Elizabeth petitioned for supply every three years, James (excluding his years of ‘personal rule’) two years, and Charles (again excluding Personal Rule) almost every year. Elizabethan parliamentarians granted supply because the queen lived ‘in most temperate manner, without excess either in building or other superfluous things of pleasure’,

Elizabethan parliamentarians granted supply because the queen lived ‘in most temperate manner, without excess either in building or other superfluous things of pleasure’, whereas parliament asked of James, ‘to what purpose is it for us to draw a silver stream out of the country into the royal cistern, if it shall daily run out thence by private cocks?’

whereas parliament asked of James, ‘to what purpose is it for us to draw a silver stream out of the country into the royal cistern, if it shall daily run out thence by private cocks?’ Tunnage and poundage, a traditionally-lifetime grant of customs duties, was given to Charles for just a year, disastrously forcing him to collect them on his own authority. Attempts by the Commons to control finance were not malicious attacks on the monarch. They were a reaction against increased expenditure and concern over misuse of funds, particularly by the duke of Buckingham. In 1625 every problem the Commons had with taxation was explained when they ‘fell into high Debates, alleging, that the Treasury was misemployed; that evil Counsels guided the King's Designs; that our Necessities arose through Improvidence; that they had need to Petition the King for a strait hand and better Counsel to manage his affairs’.

Tunnage and poundage, a traditionally-lifetime grant of customs duties, was given to Charles for just a year, disastrously forcing him to collect them on his own authority. Attempts by the Commons to control finance were not malicious attacks on the monarch. They were a reaction against increased expenditure and concern over misuse of funds, particularly by the duke of Buckingham. In 1625 every problem the Commons had with taxation was explained when they ‘fell into high Debates, alleging, that the Treasury was misemployed; that evil Counsels guided the King's Designs; that our Necessities arose through Improvidence; that they had need to Petition the King for a strait hand and better Counsel to manage his affairs’. If there was anything organised about this, it came as much from Buckingham’s enemies as from an organised, ‘modern’ parliamentary opposition.

If there was anything organised about this, it came as much from Buckingham’s enemies as from an organised, ‘modern’ parliamentary opposition.

Limited extraordinary revenue led to greater reliance on prerogative finance such as impositions, monopolies, forced loans, and ship money. But this was a breeding ground for conflict with parliament, and its increased use led to increased opposition. In addition to witnessing their raison d’etre diminish, and despite very few elections being contested, members were concerned for those they ‘represented’. Monopolies caused contention in the parliaments of 1597, 1601, and 1621. In 1601, William Spicer explained, ‘I speak not…either repining at her Majesty’s prerogative or misliking the reasons of her grants, but out of grief of heart to see the town wherein I serve pestered and continually vexed with the substitutes or viceregents of these monopolitans’. James side-stepped personal criticism in the 1621 monopolies scandal, but suffered opposition over impositions in almost every parliament of his reign. In 1610, parliamentary concern for ‘the ancient liberty of this kingdom and your subjects’ right of propriety of their lands and goods’, helped to stymie the Great Contract,

James side-stepped personal criticism in the 1621 monopolies scandal, but suffered opposition over impositions in almost every parliament of his reign. In 1610, parliamentary concern for ‘the ancient liberty of this kingdom and your subjects’ right of propriety of their lands and goods’, helped to stymie the Great Contract, and disputes in 1614 prompted an ultimatum from James: move on, grant supply, or parliament will be dissolved. The answer, in like tone, was ‘Till…it shall please God to ease us of these impositions wherewith the whole kingdom does groan, we cannot without wrong to our country give your Majesty that relief which we desire.’

and disputes in 1614 prompted an ultimatum from James: move on, grant supply, or parliament will be dissolved. The answer, in like tone, was ‘Till…it shall please God to ease us of these impositions wherewith the whole kingdom does groan, we cannot without wrong to our country give your Majesty that relief which we desire.’ The result was the Addled Parliament and a seven-year ‘personal rule’.

The result was the Addled Parliament and a seven-year ‘personal rule’.

Prerogative vs privilege

Each parliament defended their privileges, and each monarch their prerogatives, but it was the strength of the monarch’s defence that determined how oppositional parliament became. The Commons noted in their 1604 Apology that prerogative was ‘the chief and almost sole cause of all discontent and troublesome proceedings’. Although the Apology is a prime piece of evidence for the Whig theory, it is also a ‘neurotically defensive’

Although the Apology is a prime piece of evidence for the Whig theory, it is also a ‘neurotically defensive’ reaction to Continental trends, where, ‘The prerogatives of princes may easily and do daily grow’.

reaction to Continental trends, where, ‘The prerogatives of princes may easily and do daily grow’. This document, which was never agreed on by the House, is not the golden thread that proponents of the progression argument wish it to be, but the issues contained within were genuine.

This document, which was never agreed on by the House, is not the golden thread that proponents of the progression argument wish it to be, but the issues contained within were genuine.

Commandments defending the prerogative inevitably led to a contest over freedom of speech. James and Elizabeth both warned the Commons not to ‘argue and debate publicly of the matters far above their reach and capacity’, creating a backlash in the Commons. The perennial pain to prerogative Peter Wentworth repeatedly spoke in defence of free speech – without which parliament became ‘a very school of flattery and dissimulation’,

creating a backlash in the Commons. The perennial pain to prerogative Peter Wentworth repeatedly spoke in defence of free speech – without which parliament became ‘a very school of flattery and dissimulation’, – in 1571, 1576, and 1587, before he was sent to the Tower for good in 1593. In 1621 disagreement over Charles’ proposed marriage led to the Commons defending their ‘ancient and undoubted right’. In turn, James argued that, ‘These are unfit things to be handled in Parliament except your king should require it of you’. Parliament’s response angered James so much that he ripped their Protestation out of the Commons Journal and dissolved parliament shortly after.

– in 1571, 1576, and 1587, before he was sent to the Tower for good in 1593. In 1621 disagreement over Charles’ proposed marriage led to the Commons defending their ‘ancient and undoubted right’. In turn, James argued that, ‘These are unfit things to be handled in Parliament except your king should require it of you’. Parliament’s response angered James so much that he ripped their Protestation out of the Commons Journal and dissolved parliament shortly after.

Elizabeth and James, as well as Charles, had members arrested, but their management of those arrests was better. Although James asserted that he was ‘very free and able to punish any man’s misdemeanours in Parliament, as well during their sitting as after’, he waited until after parliament’s dissolution in 1622 to arrest the principal authors of the Protestation, and Wentworth’s arrest was based on actions outside parliament. But in 1626, Dudley Digges and John Eliot were arrested while parliament was sitting in an attempt to prevent Buckingham’s impeachment. Charles conceded after the Commons went on strike, but his ‘actions represented a practical authoritarianism that went far beyond anything his father had done, and they reflected a much more high-handed attitude towards parliamentary privilege than James had ever displayed.’

But in 1626, Dudley Digges and John Eliot were arrested while parliament was sitting in an attempt to prevent Buckingham’s impeachment. Charles conceded after the Commons went on strike, but his ‘actions represented a practical authoritarianism that went far beyond anything his father had done, and they reflected a much more high-handed attitude towards parliamentary privilege than James had ever displayed.’

A further tactic, used perhaps once by Elizabeth, more frequently by her successor, and to his absolute detriment by Charles, was the dissolution of parliament in anger. Both Elizabeth and Charles felt compelled to remind parliament they could ‘dissolve the meeting and send them home’, but only Charles threatened to fall ‘out of love with parliaments’ and ‘to use new counsels’.

but only Charles threatened to fall ‘out of love with parliaments’ and ‘to use new counsels’. In 1626, while not admitting any wrong-doing, parliament responded loyally to Charles’ threats: ‘They Beseech your most excellent Majesty to believe, that no earthly thing is so dear and precious to them, as that your Majesty should retain them in your grace and good opinion; and it is grief to them…that any misinformation, or misinterpretation, should at any time render their words or proceedings offensive to your Majesty.’

In 1626, while not admitting any wrong-doing, parliament responded loyally to Charles’ threats: ‘They Beseech your most excellent Majesty to believe, that no earthly thing is so dear and precious to them, as that your Majesty should retain them in your grace and good opinion; and it is grief to them…that any misinformation, or misinterpretation, should at any time render their words or proceedings offensive to your Majesty.’ The relationship could have been saved, but in dissolving parliament and refusing to deal with issues in a timely manner, Charles postponed the inevitable and allowed grievances to become more serious. The tunnage and poundage saga, which Paul Hunneyball uses as a showcase for the increased assertiveness of parliament, had such serious repercussions, not least in members holding the speaker in his chair until resolutions were read. But the actions of these men weren’t those of an organised opposition; they were the actions of an unheard and deeply frustrated group.

The relationship could have been saved, but in dissolving parliament and refusing to deal with issues in a timely manner, Charles postponed the inevitable and allowed grievances to become more serious. The tunnage and poundage saga, which Paul Hunneyball uses as a showcase for the increased assertiveness of parliament, had such serious repercussions, not least in members holding the speaker in his chair until resolutions were read. But the actions of these men weren’t those of an organised opposition; they were the actions of an unheard and deeply frustrated group.

Challenging Charles

The way challenge was handled was, then, essential to maintaining the balance between monarch and parliament. To James, parliament’s privileges ‘were derived from the grace and permission’ of his ancestors, and he acted accordingly. But with experience – and coaxing – his opinion softened in show if not in substance. In 1624 he likened the relationship between king and parliament to that between husband and wife: ‘as it is the husband’s part to cherish his wife, to entreat her kindly, and reconcile himself towards her, and procure her love by all means, so it is my part to do the like to my people’.

But with experience – and coaxing – his opinion softened in show if not in substance. In 1624 he likened the relationship between king and parliament to that between husband and wife: ‘as it is the husband’s part to cherish his wife, to entreat her kindly, and reconcile himself towards her, and procure her love by all means, so it is my part to do the like to my people’. Elizabeth understood the need for give-and-take, and knew that a flat-out refusal would only lead to more debate. Unlike Charles, she did not take criticism as a deliberate slur to her honour, and worked to address religious and financial grievances. Any other approach encouraged the Commons to look for precedent and demand their ancient rights. In this way a single issue could escalate into genuine opposition over the nature and role of parliament. This wasn’t parliament changing: it was the nature, understanding, and experience of the reigning monarch that changed.

Elizabeth understood the need for give-and-take, and knew that a flat-out refusal would only lead to more debate. Unlike Charles, she did not take criticism as a deliberate slur to her honour, and worked to address religious and financial grievances. Any other approach encouraged the Commons to look for precedent and demand their ancient rights. In this way a single issue could escalate into genuine opposition over the nature and role of parliament. This wasn’t parliament changing: it was the nature, understanding, and experience of the reigning monarch that changed.

Charles carried forward his father’s bad traits, but seemingly none of his good, and the escalation of opposition from parliament in the 1620s and into the 1640s was a product of this. Parliament had held great hopes for Charles, noting in 1625 ‘that since he began to reign, the Grievances are few or none…Wherefore it will be the wisdom of this House to take a course to sweeten all things between King and People’. That this entirely conciliatory approach degraded so quickly must be about more than institutional change or the assertiveness of parliament. His absolute belief in divine right continued from beginning to end: in 1629 he stated that ‘princes are not bound to give account of their actions, but to God alone’, while just days before his death he wrote ‘that no earthly power can justly call me, who am your king, in question as a delinquent’.

That this entirely conciliatory approach degraded so quickly must be about more than institutional change or the assertiveness of parliament. His absolute belief in divine right continued from beginning to end: in 1629 he stated that ‘princes are not bound to give account of their actions, but to God alone’, while just days before his death he wrote ‘that no earthly power can justly call me, who am your king, in question as a delinquent’. His stubbornness prevented him from compromising, and his reliance on favourites kept him secluded from parliament. In not being heard at a normal volume, parliament was forced to shout.

His stubbornness prevented him from compromising, and his reliance on favourites kept him secluded from parliament. In not being heard at a normal volume, parliament was forced to shout.

Although some parliamentary opposition was undoubtedly generated by privy council conflict, there was genuine opposition to Charles’ advisers. Neither Buckingham, with his ‘exorbitant power, and frequent misdoings’ nor the earl of Strafford, ‘that grand Apostate to the Commonwealth’,

nor the earl of Strafford, ‘that grand Apostate to the Commonwealth’, were trusted. In seeking their removal, parliament was attempting to establish a better relationship with Charles, and usher in a period of ‘stability, wealth, and strength, and honour’.

were trusted. In seeking their removal, parliament was attempting to establish a better relationship with Charles, and usher in a period of ‘stability, wealth, and strength, and honour’. Charles, in acting against those few ‘turbulent and ill-affected spirits’,

Charles, in acting against those few ‘turbulent and ill-affected spirits’, likewise hoped for harmony. As Russell says, ‘both sides continued to think…that unity would return automatically if mischief-makers were removed, and so increasingly desperate attempts to restore unity became the cause of further disunity.’

likewise hoped for harmony. As Russell says, ‘both sides continued to think…that unity would return automatically if mischief-makers were removed, and so increasingly desperate attempts to restore unity became the cause of further disunity.’

That it took parliament – and the rump of it at that – until 1649 to execute the king shows there was little ideology involved. This was not a war over the idea of monarchy, nor over the supremacy of parliament. It was brought about by Charles’ failure to understand the fine balance between monarchy and the estates. In an ever-increasing vicious circle, Charles and parliament reacted against each other, creating further opposition. But at any point up to the dissolution in 1629, the situation could have been saved. Utilising James’ analogy, the relationship between king and parliament was like a, very unequal, marriage. The marriage worked when both sides were willing to communicate and to compromise. As soon as this stopped, the sniping, complaining about ‘friends’, and paranoia set in. Counselling (or Councillors) could have helped the marriage get through the rocky patch of the late 1620s, but Charles’ attempt at a separation put an end to hope. Ultimately, it was the bad kingship of Charles, not an increasingly-defined sense of parliamentary self, that led to an increase in parliamentary opposition. The parliaments of Charles I were significantly more oppositional than his predecessors, but they didn’t intend to be.

Things to think about

- How far was the Civil War a result of Charles I's incompetence?

- How had parliament's attitude changed since the accession of Elizabeth I?

- What external factors contributed to parliament's change of attitude?

- How much did Charles' use of favourites alienate parliament?

- Could the needs of prerogative an liberty ever be balanced effectively?

- Was this period the birth of the modern parliament?

- Could the Civil War have been avoided?

Things to do

- A huge collection of parliamentary records, including all of the Commons and Lords journals, the Rushworth Papers and other parliamentary diaries, are available at British History Online. Conduct your own research to decide whether parliament's antagonism to the monarch increased over the period.

- The Houses of Parliament are open to visitors Monday to Saturday, and offer a range of visiting experiences, from self-guided audio tours to family tours and the chance to watch debates or committees in session. More information about visiting can be found here.

- Banqueting House is not just the place where Charles I was executed: its artwork also illustrates the Stuart monarchy's self-belief and ideology. You can find out more information about visiting and buy tickets here.

Further reading

Few recent books have been published that consider parliaments over the reigns of Elizabeth, James, and Charles. The last one to do so, and that is still useful and infinitely readable, is Conrad Russell's The Crisis Of Parliaments: English History, 1509-1660. There are many other books which consider the parliaments of the late Tudors and early Stuarts separately. The best of these are Michael Grave's Elizabethan Parliaments 1559-1601 and Robert Lockyer's The Early Stuarts: A Political History of England 1603-1642. Richard Cust provides an excellent political biography of Charles I in Charles I: A Political Life.