Key facts about Henry VIII

- Henry VIII was king of England between 1509 and 1547

- He is mostly famous for having six wives and being remarkably fat

- He caused England’s break from Rome and oversaw the start of the English Reformation

- He is not so easy to understand as is often thought, and there are debates about his personality, his love life, his religious attitudes, and his style of government

People you need to know

- Arthur, Prince of Wales – first-born son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, who died in 1502

- cleves-stinky-and-ugly" target="_blank" title="Anne of Cleves">Anne of Cleves – Henry VIII’s fourth wife, whom he found unattractive and divorced

- Anne Boleyn – Henry VIII’s second wife and mother of Elizabeth, whom he executed in 1536

- Catherine of Aragon – Henry VIII’s first wife, daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, wife of Arthur and later of Henry VIII, mother of Mary, and aunt of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

- Thomas Cromwell – commoner and chief adviser to Henry VIII between 1532 and 1540

- John Dudley – during Henry VIII’s reign, Lord Lisle and Lord Admiral of England at the time of the French invasion. He later took a major role in the regency council of Edward VI.

- Elizabeth of York – daughter of Edward IV (d. 1483), wife of Henry VII, and mother to Henry VIII

- Francis I – king of France between 1515 and 1547

- Henry V - warrior king of England between 1413 and 1422, who gained a famous victory at the Battle of Agincourt.

- Henry VII – king of England between 1485 and 1509

- Henry VIII – king of England between 1509 and his death on 28 January 1547

- Hans Holbein the Younger – German and Swiss artist who became the King’s Painter to Henry VIII.

- Kathryn Howard – Henry VIII’s fifth wife, whom he executed for infidelity

- Thomas Howard – 3rd Duke of Norfolk, rival of Thomas Cromwell, and uncle to Anne Boleyn and Kathryn Howard.

- Catherine Parr – Henry VIII’s sixth and final wife

- Jane Seymour – Henry VIII’s third and favourite wife, who died after giving birth to the future Edward VI

- Thomas Wolsey – cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, and chief adviser to Henry VIII between 1515 and 1529

Henry VIII could be called England’s most memorable king. Everyone has seen his image: tall, imposing, and rotund. Likewise, everyone knows that he had six wives, and that he divorced two of them, and executed a further two. He brought the Reformation to England, breaking from the Roman Church, creating the royal supremacy, and dissolving the monasteries. But behind these headlines, there are other facts, often surprising and neglected, that make Henry VIII a much more interesting man.

Man and boy

Prince Henry was born on 28 June 1491 at Greenwich, younger son to the ‘Lancastrian’ Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV. Henry’s elder brother, Arthur, was destined to become king, and Henry was therefore given little training in statecraft. Even after his brother’s death in 1502 from the sweating sickness, Henry remained sheltered from the world of politics.

Henry VII died on 21 April 1509, and the almost-eighteen-year-old Henry VIII became king. His accession was greeted with glee: he was everything a young king ought to be, good humoured and lively, with happy manners. He was handsome too, slim, athletic and measuring an imposing 6’2”, when the average height for men was 5’8”. Those who met the young Henry waxed lyrical about his good looks. A Venetian ambassador called him ‘the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on’ with a ‘round face so very beautiful, that it would become a pretty woman’.

Those who met the young Henry waxed lyrical about his good looks. A Venetian ambassador called him ‘the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on’ with a ‘round face so very beautiful, that it would become a pretty woman’.  Not just his looks, but his personality charmed those around him: he was generous and fun-loving, arranging exceptional banquets and escapades, including having his court dress up as Robin Hood and the Merry Men. He loved dancing, and was a keen – and good – jouster and hunter, often tiring 10 horses a day before he himself grew tired or bored. Musically gifted – in 1517 he entertained a visiting French embassy by singing and playing on every musical instrument available – he was also considered something of an intellect, with Erasmus describing him as ‘a universal genius’.

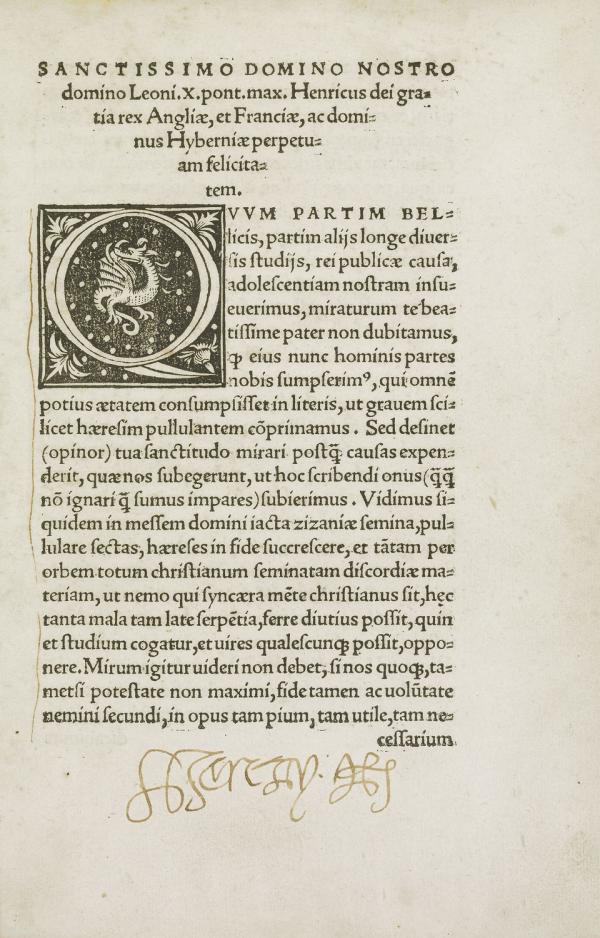

Not just his looks, but his personality charmed those around him: he was generous and fun-loving, arranging exceptional banquets and escapades, including having his court dress up as Robin Hood and the Merry Men. He loved dancing, and was a keen – and good – jouster and hunter, often tiring 10 horses a day before he himself grew tired or bored. Musically gifted – in 1517 he entertained a visiting French embassy by singing and playing on every musical instrument available – he was also considered something of an intellect, with Erasmus describing him as ‘a universal genius’.  This was helped by his fondness for books, and he collected a library that, unlike many other monarchs, didn’t just contain ‘picture’ (or what we would call ‘coffee table’) books. That they weren’t simply for display, and that he read and digested them, is shown through the numerous notes in their margins written in Henry’s own hand.

This was helped by his fondness for books, and he collected a library that, unlike many other monarchs, didn’t just contain ‘picture’ (or what we would call ‘coffee table’) books. That they weren’t simply for display, and that he read and digested them, is shown through the numerous notes in their margins written in Henry’s own hand.

But as Henry VIII aged, he became less the ideal prince and more the unbearable tyrant. He suffered from temper tantrums, frequently hitting his adviser Thomas Cromwell and ultimately sending him to the block. Nor was Cromwell the only person to be executed on Henry’s order: scores of high-profile people – people who had known and worked with Henry VIII for years – were likewise killed (including, of course, two of his wives). Sixty-eight of these were condemned not under common law trial but through acts of attainder because they either weren’t actually guilty of treason or because the evidence was so flimsy they would never have been convicted. One such example is Margaret Pole, the infirm 67-year-old Countess of Salisbury who was one of the few surviving members of the Plantagenet dynasty. Accused of treason in 1539 – her son had disapproved of Henry VIII’s religious policy and the marriage to Anne Boleyn, and evidence was ‘discovered’ that linked her to the Pilgrimage of Grace – she was executed in 1541, being led from her cell ‘not knowing of what crime she was accused, nor how she had been sentenced’. The inexperienced executioner then ‘literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner’, taking 11 attempts to sever her head from her body.

One such example is Margaret Pole, the infirm 67-year-old Countess of Salisbury who was one of the few surviving members of the Plantagenet dynasty. Accused of treason in 1539 – her son had disapproved of Henry VIII’s religious policy and the marriage to Anne Boleyn, and evidence was ‘discovered’ that linked her to the Pilgrimage of Grace – she was executed in 1541, being led from her cell ‘not knowing of what crime she was accused, nor how she had been sentenced’. The inexperienced executioner then ‘literally hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner’, taking 11 attempts to sever her head from her body.

Henry also became known as fickle, greedy, ‘and marvellously excessive in drinking and eating, so that people worth credit say he is often of a different opinion in the morning than after dinner.’ His waist expanded from 35 inches to a massive 54 inches, and his weeping leg ulcer – a remnant from a sporting injury, but not helped by his diet - left a deeply unpleasant lingering smell. Obviously, he became unfit: the ulcer and his increasing size made it impossible for him to enjoy the physical pursuits of his earlier years, and left him in a great deal of pain.

His waist expanded from 35 inches to a massive 54 inches, and his weeping leg ulcer – a remnant from a sporting injury, but not helped by his diet - left a deeply unpleasant lingering smell. Obviously, he became unfit: the ulcer and his increasing size made it impossible for him to enjoy the physical pursuits of his earlier years, and left him in a great deal of pain.

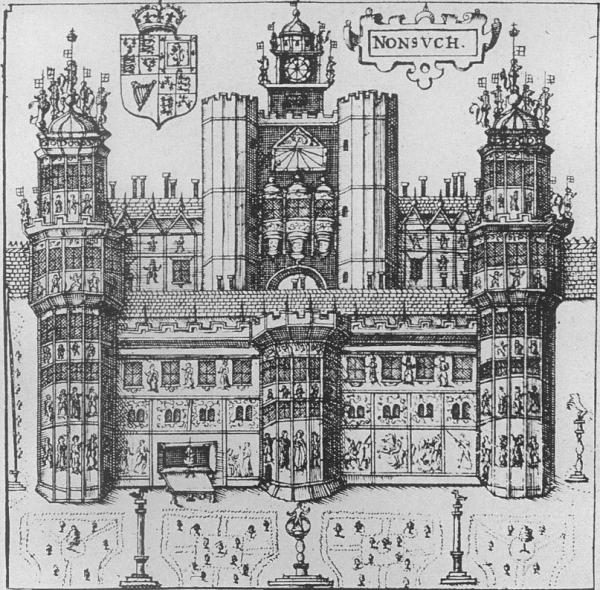

Despite the full coffers left to Henry VIII by his father’s careful financial management, and the additional income from the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry left the country in deficit. Part of this was due to his unnecessary wars, but it was also partly due to his unchecked acquisitive nature. Anything that could add to his magnificence, that could improve his status and grandeur, he wanted. As historian Eric Ives asked, ‘Why [own] over a hundred pairs of embroidered sleeves? Why in the cash-strapped 1540s did his agents conspire to keep him from hearing about jewels on the market? And why, having inherited thirteen houses did he acquire and retain thirty or so more, many of which he never visited?’  Even when fear of foreign invasion was at its height, in late 1530s and early 1540s, Henry still considered it appropriate to spend £170,000 on upgrading Hampton Court, Whitehall, and Nonsuch Palace.

Even when fear of foreign invasion was at its height, in late 1530s and early 1540s, Henry still considered it appropriate to spend £170,000 on upgrading Hampton Court, Whitehall, and Nonsuch Palace.

The young Henry seems so remarkably different from the old Henry that many historians suggest he suffered some sort of personality change around 1530, caused either by a psychological breakdown or an injury. This charming and good-looking young man had, by the end of his life, become an obese, self-centred, bad-tempered, paranoid monster. Undoubtedly, the constant pain from his ulcer made him grumpy, but is this enough of a justification for his behaviour? Some historians believe a change of character was triggered by a head injury, others that it was a crisis of confidence caused by his increasing age. Suzannah Lipscomb argues that a jousting accident that reopened an old leg wound affected him both physically and mentally, preventing him from attaining the alpha-male vision he had of himself. However, much of the praise for young Henry centred on his love of fun, his charm, and his looks: there is little that mentions his inherent virtues. Perhaps, simply, his increasing age allowed his true nature to be seen more clearly.

Divorced, beheaded, died…

Less than two months after Henry VIII’s accession, Henry married his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon. The match was designed to bring the countries of Spain and England closer together, and secure England’s place in Europe, but required special papal dispensation for consanguinity, based on the prior marriage of Catherine and Arthur. The marriage started well, and a degree of trust and affection developed between them: Henry even left Catherine ruling as regent, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated., because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated. while he was away in France. But children – or the lack thereof – became an issue. The couple’s first daughter was stillborn in January 1510; their first son, Henry, died in 1511 aged just seven weeks, and they suffered two further stillbirths in 1514 and 1515. Eventually, on 18 February 1516, Catherine gave birth to Princess Mary. She wasn’t the hoped-for son and heir, but she was a start.

The match was designed to bring the countries of Spain and England closer together, and secure England’s place in Europe, but required special papal dispensation for consanguinity, based on the prior marriage of Catherine and Arthur. The marriage started well, and a degree of trust and affection developed between them: Henry even left Catherine ruling as regent, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated., because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated. while he was away in France. But children – or the lack thereof – became an issue. The couple’s first daughter was stillborn in January 1510; their first son, Henry, died in 1511 aged just seven weeks, and they suffered two further stillbirths in 1514 and 1515. Eventually, on 18 February 1516, Catherine gave birth to Princess Mary. She wasn’t the hoped-for son and heir, but she was a start.

But there was no happy ending for Catherine of Aragon. By 1525, Catherine still hadn’t produced the longed-for heir and, now aged 40, nor was she likely to. Henry, never exactly faithful to his wife, started looking around for a replacement and fixed upon Anne Boleyn. There is much debate over who initiated the courtship, who insisted on marriage, and how affectionate it was. We have Henry’s love letters to Anne, but not the replies, and these suggest he was infatuated with her. Anne’s feelings can only be guessed from the reports of others, many of which are critical of her. The couple married officially in January 1533 and eight months later Anne gave birth to a baby girl, Elizabeth. The marriage had not been easy to arrange: it had resulted in a formal break with Rome, which simplistically-put led to the English Reformation, and to the downfall of Henry’s chief adviser, Cardinal Wolsey. Nor was it easy in itself and is best described as tempestuous, with the couple swinging from adoration to furious argument. Jealousy tainted the match, culminating in Anne’s execution for treason in 1536. She had allegedly had adulterous affairs with several men, including her brother, and spoken about the king’s potential death. The actual reason for Anne’s death is disputed, but it is likely it had something to do with her inability to provide a healthy male heir.

The marriage had not been easy to arrange: it had resulted in a formal break with Rome, which simplistically-put led to the English Reformation, and to the downfall of Henry’s chief adviser, Cardinal Wolsey. Nor was it easy in itself and is best described as tempestuous, with the couple swinging from adoration to furious argument. Jealousy tainted the match, culminating in Anne’s execution for treason in 1536. She had allegedly had adulterous affairs with several men, including her brother, and spoken about the king’s potential death. The actual reason for Anne’s death is disputed, but it is likely it had something to do with her inability to provide a healthy male heir.

Henry moved swiftly on to his third and favourite wife, Jane Seymour. She had caught his eye by at least January 1536, and Anne blamed her miscarriage of that year partly on worry over Henry’s attraction to Jane. Not one for mourning, Henry was engaged to Jane just a day after Anne’s execution, and they married on 30 May 1536. Jane was milder than her predecessor, and much more reserved, for example banning the French fashions at court that Anne had loved. Although she could read and write a little, she excelled at the proper female pursuits of household management and needle work. She also fulfilled that other wifely duty when she provided him with an heir, the future Edward VI, born on 12 October 1537. Edward was the only child Jane would have: after a difficult birth, she died 12 days later, on 24 October 1537.

Not one for mourning, Henry was engaged to Jane just a day after Anne’s execution, and they married on 30 May 1536. Jane was milder than her predecessor, and much more reserved, for example banning the French fashions at court that Anne had loved. Although she could read and write a little, she excelled at the proper female pursuits of household management and needle work. She also fulfilled that other wifely duty when she provided him with an heir, the future Edward VI, born on 12 October 1537. Edward was the only child Jane would have: after a difficult birth, she died 12 days later, on 24 October 1537.

Henry’s next replacement bride was Anne of Cleves, largely at the suggestion of his new chief adviser Thomas Cromwell, who was aiming to improve relations with the German Protestant states. But Henry, despite liking the picture of Anne painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, declared that he found Anne in person unattractive and smelly. He married her anyway on 6 January 1540, but was apparently so repulsed by her that he couldn’t perform. The marriage was quickly annulled – due to lack of consummation – and Anne became ‘the King’s Beloved Sister’. Cromwell was just as quickly executed for treason.

On the day of Cromwell’s death, 28 July 1540, Henry married Kathryn Howard, the niece of Cromwell’s political rival and nemesis, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk. This lively, pretty teenager Henry most certainly did find attractive, but sadly for Kathryn it was probably not reciprocated. Instead, she found herself accused not only of indiscretions prior to her marriage to Henry but also of adultery during her marriage, and was placed in a convent until a law could be passed that allowed Henry to execute her, which he did less than two years after their wedding, on 13 February 1542.

Catherine Parr was Henry’s sixth and final wife, from 1543 until his death in 1547. Older and wiser than most of her predecessors, Catherine had already been married twice before. Although often believed to have been plain, dull, and nothing more than a nurse to her husband, Catherine was in fact pretty and intelligent, taking an interest in religion and publishing two books. She survived not just a plot against her, but also Henry. She married her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour, on 12 July 1547, six months after the death of Henry VIII. Their romantic attachment had begun before her betrothal to Henry (although she had, for very obvious reasons, been faithful to Henry during their marriage), but was cut prematurely short when she died six days after the birth of her daughter, on 5 September 1548.

Catherine had already been married twice before. Although often believed to have been plain, dull, and nothing more than a nurse to her husband, Catherine was in fact pretty and intelligent, taking an interest in religion and publishing two books. She survived not just a plot against her, but also Henry. She married her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour, on 12 July 1547, six months after the death of Henry VIII. Their romantic attachment had begun before her betrothal to Henry (although she had, for very obvious reasons, been faithful to Henry during their marriage), but was cut prematurely short when she died six days after the birth of her daughter, on 5 September 1548.

Defender of the Faith

Next to his love life, Henry VIII is best known for his religious policies, in particular for introducing Protestantism to England. After all, he broke from Rome, declared himself supreme head of the English church, had the Bible translated into the vernacular and placed in churches up and down the country, dissolved the monasteries, and executed a number of prominent Catholics. From this, it would be possible to imagine Henry as a revolutionary, dedicated to far-reaching religious reform. But the situation was not so simple.

The young Henry was considered by many contemporaries as deeply religious, and he certainly fancied himself as a bit of a theologian. He attended Mass daily, gave alms to the poor, and annotated the margins of religious works. In 1521, Henry wrote – with help – Assertio Septem Sacramentorum, or The Defence of the Seven Sacraments, a defence of Catholicism against the claims of Luther, and was awarded the title Fidei Defensor, or Defender of the Faith, by the Pope. But was this just conventional belief or a superficial show of religiosity? After all, what better way to continue his attempts at one-upmanship against Francis I than being granted such a title? However, no matter how deeply Henry’s Catholicism really reached, the young Henry considered himself a Catholic king, chosen as such by God Himself.

So, why did Henry take the path of the reformers? Many contemporaries and historians have seen his actions as not inspired by devotion to a cause, but as ‘the arbitrary acts of a man whose prime concern was his own stability and satisfaction.’ The Elizabethan Catholic Nicholas Sanders thought that ‘He gave up the Catholic faith for no other reason in the world than that which came from his lust and wickedness.’  There is no doubt that many of the acts of reformation undertaken by Henry benefitted him: the Dissolution of the Monasteries brought him much-needed extra income; the break with Rome allowed him to marry Anne Boleyn; royal, rather than papal, supremacy enabled Henry to achieve more power and improve his self-image; and the Bible in the vernacular supported his claims of supremacy. Perhaps he was also influenced by those around him, in particular by Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell.

There is no doubt that many of the acts of reformation undertaken by Henry benefitted him: the Dissolution of the Monasteries brought him much-needed extra income; the break with Rome allowed him to marry Anne Boleyn; royal, rather than papal, supremacy enabled Henry to achieve more power and improve his self-image; and the Bible in the vernacular supported his claims of supremacy. Perhaps he was also influenced by those around him, in particular by Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell.

Evidence of his lack of commitment to, and real belief in, reform has always been found in his half-way policies and his ‘back-tracking’ in the 1540s. He had sympathy with several (what would now be considered) Catholic doctrines, such as the Latin Mass and the belief of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist; and rejected key Protestant ones, such as justification by faith alone (Henry believed that charity was as important as faith). He even grew concerned over access to the Bible, and Parliament enacted that ‘no women nor artificers, [ap]prentices, journeymen, serving men of the degrees of yeomen or under, husbandmen nor labourers’ should read the Bible as they had ‘increased in divers naughty and erroneous opinions, and by occasion thereof fallen into great division and dissension among themselves’. The Bible should therefore be restricted to upper-class men who were capable of making the ‘right’ decisions. His targets of persecution show this mixed approach: those who were too radical were burnt as heretics, and those who determinedly supported the papacy were executed as traitors.

His targets of persecution show this mixed approach: those who were too radical were burnt as heretics, and those who determinedly supported the papacy were executed as traitors.

However, in 1533 there was no hard and fast path toward reform. Luther had only written his theses 16 years previously, and no ‘correct’ way had been found among the competing philosophies of different groups: was there a real presence in the Eucharist, was it transubstantiation, or was it merely metaphorical; what about notions of predestination – was it only God’s select who made it to Heaven? These were heady days of experimentation and debate, when even the term ‘Protestant’ had no clear meaning other than referring to a handful of German states. Instead, reformers were either called as such or known as ‘evangelicals’. It is wrong, then, to place labels on Henry’s beliefs that didn’t clearly exist at the time. The best we can label this mixture of neither fully-Catholic nor fully-Protestant beliefs during the reign of Henry VIII is as the Henrician Settlement.

Man O’War

Henry VIII was ‘ever desirous to serve Mars’ and to be a great military leader. A fan of tales of heroism and chivalry, he was inspired by the likes of the Black Prince and Henry V, as well as David and others from the Old Testament. He wanted to be important, and to be recognised as a player in Continental affairs.

A fan of tales of heroism and chivalry, he was inspired by the likes of the Black Prince and Henry V, as well as David and others from the Old Testament. He wanted to be important, and to be recognised as a player in Continental affairs. The problem was, when Henry came to power, there was no-one to fight and England was at peace with her old enemies of Scotland and France.

The problem was, when Henry came to power, there was no-one to fight and England was at peace with her old enemies of Scotland and France. To prove his prowess, Henry VIII had to pick a fight. In what seems to be an attempt to restart the Hundred Years’ War, Henry invaded France. He achieved some victories, including at the Battle of the Spurs on 30 June 1513 and, thanks to the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France that had James IV of Scotland attacking England’s northern border, at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513.

To prove his prowess, Henry VIII had to pick a fight. In what seems to be an attempt to restart the Hundred Years’ War, Henry invaded France. He achieved some victories, including at the Battle of the Spurs on 30 June 1513 and, thanks to the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France that had James IV of Scotland attacking England’s northern border, at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513.

When not pursuing an aggressive foreign policy, Henry VIII attempted to increase his importance on the international stage in other ways, in arranging dynastic marriages between his children and those of other monarchs, and in spearheading peace treaties. The grandest of these was the Treaty of London, signed in 1518 by almost all of the European powers. Originally the brainchild of Pope Leo X, who wanted peace in Europe as a precursor to another crusade, the plan for a multi-national non-aggression pact was taken up and promoted by Thomas Wolsey. Initially it was a complete success and was celebrated as such at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520. In June of that year Henry VIII and Francis I met across a valley to display their magnificence and friendship. Instead of competing on the battlefield, the two monarchs tried to outshine each other with lavish feasts, fantastic jousts, and fine music and games. Even their tents and clothes were designed to dazzle, and the name of the summit comes from the huge amounts of cloth of gold used. The expense was enormous – Henry took his entire court to the summit and even had a steel mill dismantled and remade on his side – with the food and drink alone costing £8,839 2s 4d. But in the end it was all for nothing: by 1522 the treaty that Henry had helped to make lay in tatters, and England was once again at war with France.

But in the end it was all for nothing: by 1522 the treaty that Henry had helped to make lay in tatters, and England was once again at war with France.

Despite Henry VIII’s victories, including taking more French land than any English monarch since Henry V, Henry’s foreign and military policy is generally viewed as a failure. The gains he made tended not to last long and his strategy has been criticised. For example, when the infant James V came to the throne after his father’s death at the Battle of Flodden, Henry did not push his advantage, instead allowing the Auld Alliance to be strengthened. His dream of conquering France was most certainly flawed, for much had changed in the past 100 years: France was in a stronger position, its internal politics less chaotic and its borders firmer, and victory was even harder for Henry VIII than for Henry V. The resultant strain of Henry’s wars on the economy led to social unrest and the impoverishment of many. As John Guy wrote, in chasing his chivalric dream, Henry ‘wasted men, money, and equipment.’

However, posterity might have been too quick to judge. Henry’s improvement in coastal defences, particularly in the strengthening and building of castles, was good. The castles placed strategically along England’s southern coast from Cornwall to Kent were used into the 20th century, and were short and sturdy. Designed with the new artillery-based warfare in mind, they were also exceptionally difficult to see – and therefore hit – from the sea.

The castles placed strategically along England’s southern coast from Cornwall to Kent were used into the 20th century, and were short and sturdy. Designed with the new artillery-based warfare in mind, they were also exceptionally difficult to see – and therefore hit – from the sea.

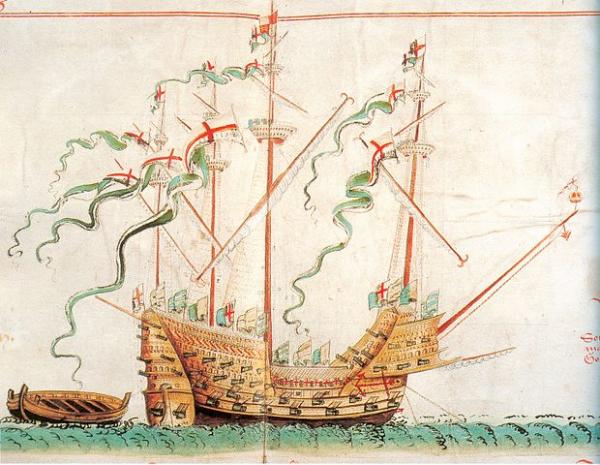

Henry’s investment in the navy was another progressive step, and he is considered the father of the Royal Navy. Interested in maritime matters from a young age, he expanded and formalised England’s naval arrangements. Under previous monarchs, the navy was ad hoc and part-time. In times of need merchant ships were hired or commandeered, sailors were hired, and victualling was not centrally organised. All of this changed under Henry VIII. Although he inherited five ships from his father, new purpose-built warships were commissioned and built throughout Henry VIII’s reign. Like the castles, these ships were designed with artillery in mind: the 1,500-tun

Under previous monarchs, the navy was ad hoc and part-time. In times of need merchant ships were hired or commandeered, sailors were hired, and victualling was not centrally organised. All of this changed under Henry VIII. Although he inherited five ships from his father, new purpose-built warships were commissioned and built throughout Henry VIII’s reign. Like the castles, these ships were designed with artillery in mind: the 1,500-tun Henry Grace à Dieu, for example, was launched in 1514 with two decks bristling with gunports and cannons.

Henry Grace à Dieu, for example, was launched in 1514 with two decks bristling with gunports and cannons. To supply his new permanent navy with weapons and equipment Henry encouraged the development of industry in England, turning the Weald once again into a centre of iron production that continued well into the eighteenth century. Overseeing these developments was a newly established King's Majesty's Council of his Marine, which eventually became the Navy Board and Admiralty. For the first time, England’s navy had the proper resources and structure to enable it to fight well. Henry’s naval improvements had far-reaching consequences and, arguably, set England on the path to empire.

To supply his new permanent navy with weapons and equipment Henry encouraged the development of industry in England, turning the Weald once again into a centre of iron production that continued well into the eighteenth century. Overseeing these developments was a newly established King's Majesty's Council of his Marine, which eventually became the Navy Board and Admiralty. For the first time, England’s navy had the proper resources and structure to enable it to fight well. Henry’s naval improvements had far-reaching consequences and, arguably, set England on the path to empire.

An all-powerful king?

Henry VIII liked to present himself as all-powerful, the supreme being in England, and second only to God. His portraits show it, as do his actions in foreign policy and religion. Yet was this really the case: was Henry, and Henry alone, responsible for all the decisions that were made during his reign? Regardless of what his propaganda might say, a number of clever, articulate, and persuasive men – and women – had his ear during the almost-forty years he was on the throne, and it has long been debated how much of them we have seen in Henry’s actions.

Geoffrey Elton saw Henry as ‘far from masterful, competent or in charge’, pointing to evidence such as the dying Wolsey’s advice to Sir William Kingston, constable of the Tower, to ‘Be well advised and assured what matter ye put in [the King’s] head, for ye shall never pull it out again’. Being quite childlike in his moods and approach to life he could be swayed by opinion, or manipulated by carefully chosen words. For example, the fact that Henry seemed to take a more conservative approach to religion after the execution of Cromwell suggests that it was actually Cromwell who was the puppet master of the Reformation. The Protestant martyrologist John Foxe agreed: ‘Thus while good counsel was about him, and could be heard, the king did much good. So again, when sinister and wicked counsel, under subtle and crafty pretences, had gotten once the foot in, thrusting truth and verity out of the prince’s ears, how much religion and all good things went prosperously forward before, so much, on the contrary side, all revolted backward again.’

Being quite childlike in his moods and approach to life he could be swayed by opinion, or manipulated by carefully chosen words. For example, the fact that Henry seemed to take a more conservative approach to religion after the execution of Cromwell suggests that it was actually Cromwell who was the puppet master of the Reformation. The Protestant martyrologist John Foxe agreed: ‘Thus while good counsel was about him, and could be heard, the king did much good. So again, when sinister and wicked counsel, under subtle and crafty pretences, had gotten once the foot in, thrusting truth and verity out of the prince’s ears, how much religion and all good things went prosperously forward before, so much, on the contrary side, all revolted backward again.’

Yet Henry himself thought he was not so easily moved, nor so easily read, jesting that ‘If I thought my cap knew my counsel, I would cast it into the fire and burn it’.  Nor did he have any problems with disposing of those advisers who displeased him: Wolsey was on his way to answer charges of treason when he died of natural causes, and Cromwell was executed. If those close to Henry manipulated him, they did so at their peril. Furthermore, where Henry was truly interested in something, he would override advice. So, in 1545 John Dudley, who was then Lord Lisle and Lord Admiral of England, had to defer to Henry in every major naval decision, including the anchoring of ships off Portsmouth, the selection of new captains, the use of new stratagems, and the timing of strikes.

Nor did he have any problems with disposing of those advisers who displeased him: Wolsey was on his way to answer charges of treason when he died of natural causes, and Cromwell was executed. If those close to Henry manipulated him, they did so at their peril. Furthermore, where Henry was truly interested in something, he would override advice. So, in 1545 John Dudley, who was then Lord Lisle and Lord Admiral of England, had to defer to Henry in every major naval decision, including the anchoring of ships off Portsmouth, the selection of new captains, the use of new stratagems, and the timing of strikes.

Perhaps it was Henry’s character, his temper tantrums and his mood swings, that have led to this belief that Henry’s mind could be easily changed by outside forces. In the sixteenth century, just as before, people would much rather criticise a monarch’s advisers than the monarch himself. Yes, Henry blamed Norfolk and cronies for the execution of Cromwell, exclaiming that ‘upon light pretexts, by false accusations, they made him put to death the most faithful servant he ever had.’ Yet Henry had been embarrassed, and had his masculinity questioned, by the debacle over Anne of Cleves.

Yet Henry had been embarrassed, and had his masculinity questioned, by the debacle over Anne of Cleves. He was angry and lashed out: it can’t have taken much convincing for Henry to make Cromwell a scapegoat. Ultimately, the scandals and paradoxes, the questions and puzzles of Henry VIII’s reign can all be solved by understanding the damaged, fickle, and tempestuous character of the man himself.

He was angry and lashed out: it can’t have taken much convincing for Henry to make Cromwell a scapegoat. Ultimately, the scandals and paradoxes, the questions and puzzles of Henry VIII’s reign can all be solved by understanding the damaged, fickle, and tempestuous character of the man himself.

Things to think about

- Did Henry VIII’s personality change and, if so, what caused it?

- Was Henry ever a good or pleasant man?

- Did Henry love any, or all, of his wives, and was he even capable of love (rather than infatuation)?

- What were Henry’s religious beliefs, if any?

- Why did Henry introduce the Reformation to England?

- How good was Henry VIII’s foreign and military policy?

- Was Henry easily swayed by his advisers or by factions at court?

Things to do

- Given that Henry VIII collected so many properties, it is hardly surprising that many are still standing and open to visitors. Some of those most closely associated with Henry and his family include Hampton Court, Windsor Castle, and the Tower of London.

- Henry’s religious policy included the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The ruins of many of these still litter the countryside, and others have been turned into lay houses. Some of the best include Glastonbury Abbey, Battle Abbey and Fountains Abbey. Find one near you to visit.

- The Mary Rose was raised from the Solent in 1982 and is undergoing conservation at Portsmouth. The museum built up around her is fantastic and worth a visit.

- Many of the state papers and other primary sources covering Henry VIII’s reign are available online at http://www.british-history.ac.uk.

Further reading

It is possible to fill whole libraries just with books on Henry VIII, and there is a need to be selective. Easy, and good, reads include Alison Weir's Henry VIII: King and Court, John Guy's Henry VIII: The Quest for Fame (part of the Penguin Monarchs series), J.J. Scarisbrick's Henry VIII (part of the Yale English Monarchs series), and Suzannah Lipscomb's 1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII.