Key facts about Thomas Cromwell

- Thomas Cromwell was adviser to Henry VIII from 1532 until 1540

- He was executed without trial for treason and heresy

- He helped to introduce religious reform in England

- He helped to change the way England was governed from a medieval system to a modern one

People you need to know

- Anne Boleyn - the second wife of Henry VIII. Find out more about Anne Boleyn here.

- Eustace Chapuys - a diplomat who served Charles V (the Holy Roman Emperor) as Imperial ambassador to England from 1529 until 1545.

- Anne of Cleves - Henry VIII's fourth wife, whom Henry found unattractive. He had the marriage annulled and she became the 'King's Beloved Sister'. Find out more about Anne of Cleves here.

- Thomas Cromwell - a commoner, lawyer and politician who was Henry VIII's chief minister from 1532 until 1540.

- Henry VIII - king from 1509 until 1547.

- Kathryn Howard - fifth wife of Henry VIII.

- Thomas Howard, duke of Norfolk - adviser to Henry VIII, and uncle to Anne Boleyn and Kathryn Howard.

- Reginald Pole - a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury.

- Thomas Wolsey - a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, who fell from favour in 1529.

Born around 1485, Thomas Cromwell rose from almost-common stock to become, as Henry VIII's adviser, one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. His fall was equally as great, and he was executed without trial on 28 July 1540 for heresy and treason. Down through history, he has been viewed as a cynical, Machiavellian writer Machiavelli's book 'The Prince' which was dedicated to Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, on the Medici family's return to… writer Machiavelli's book 'The Prince' which was dedicated to Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, on the Medici family's return to… writer Machiavelli's book 'The Prince' which was dedicated to Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, on the Medici family's return to… writer Machiavelli's book 'The Prince' which was dedicated to Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, on the Medici family's return to… upstart, who drove through reform for his own gain. More recently, historians and writers have looked through the propaganda to get a better understanding of the real Cromwell. They have shown him to be something of a Renaissance man and idealist who was charming, engaging, witty, and unconstrained by his humble origins: a remarkable man who lived in remarkable times.

upstart, who drove through reform for his own gain. More recently, historians and writers have looked through the propaganda to get a better understanding of the real Cromwell. They have shown him to be something of a Renaissance man and idealist who was charming, engaging, witty, and unconstrained by his humble origins: a remarkable man who lived in remarkable times.

Cromwell's early life

Cromwell was a self-made man from a relatively humble family. A son of a shearman-blacksmith-brewer from Putney, he travelled Europe in his younger years, and even served as a mercenary during the Italian wars in 1503. The beginnings of the fortune he made, and the education he received, during these travels allowed him to set up as a merchant around 1510, with a particular interest in the Low Countries. For the next 15 years, he also studied the law, allowing him to gain admission to Gray’s Inn in 1524. From there his reputation grew, particularly in what could be called ‘commercial law’. By the late 1520s he was working as Cardinal Wolsey’s man of business.

The beginnings of the fortune he made, and the education he received, during these travels allowed him to set up as a merchant around 1510, with a particular interest in the Low Countries. For the next 15 years, he also studied the law, allowing him to gain admission to Gray’s Inn in 1524. From there his reputation grew, particularly in what could be called ‘commercial law’. By the late 1520s he was working as Cardinal Wolsey’s man of business. He entered parliament on the strength of his connection with the cardinal, but managed to survive Wolsey’s downfall and was able to take his place as Henry VIII’s chief minister in 1532.

He entered parliament on the strength of his connection with the cardinal, but managed to survive Wolsey’s downfall and was able to take his place as Henry VIII’s chief minister in 1532.

Cromwell as chief minister

During the eight short years at the height of his power, Cromwell was a busy man. He had come across reformist ideas while on the Continent and now back in England he pushed the 'protestant'

Reformation.

Reformation. ideas, distancing England from Rome and dissolving the monasteries.

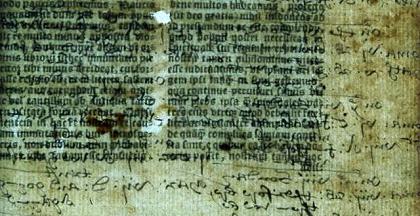

ideas, distancing England from Rome and dissolving the monasteries. brought £1.3 million into the state’s coffers and saw the transference of land from the medieval period's biggest land owner to the Crown. Those who disagreed with the process or the reasons behind it were imprisoned, tortured and executed. It was one of the biggest upheavals in English history, directly affecting 12,000 monks, nuns and others in religious orders (at a time when the population was estimated to be about 2.75 million). He also used his experience of the city states of Italy to change politics and governance in England. This work made statute, rather than royal decree, central, leading historians such as Elton to name him a parliamentarian.

brought £1.3 million into the state’s coffers and saw the transference of land from the medieval period's biggest land owner to the Crown. Those who disagreed with the process or the reasons behind it were imprisoned, tortured and executed. It was one of the biggest upheavals in English history, directly affecting 12,000 monks, nuns and others in religious orders (at a time when the population was estimated to be about 2.75 million). He also used his experience of the city states of Italy to change politics and governance in England. This work made statute, rather than royal decree, central, leading historians such as Elton to name him a parliamentarian. He acquired a number of formal roles during his rise, none of which he seemed to neglect and for each he worked hard.

He acquired a number of formal roles during his rise, none of which he seemed to neglect and for each he worked hard. He was involved in the familial concerns of the king, including the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn

He was involved in the familial concerns of the king, including the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn and famously pushed the marriage of Henry to Anne of Cleves, with disastrous consequences (at least for himself).

and famously pushed the marriage of Henry to Anne of Cleves, with disastrous consequences (at least for himself).

Cromwell the man

As one of the main proponents in severing the link with Rome, Cromwell has been painted both as a man of no faith (in the Machiavellian sense of serving that which best served himself) and a man of extremely strong protestant conviction. It is likely we will never know exactly what he thought, as he never made his own religious views known. We therefore have to look at his actions to achieve any idea. Many see his actions as derived from deep religious belief, inspired by his time on the continent. Diarmaid MacCulloch points to the fact that he was in close contact with reformists on the continent, without the king’s permission or knowledge, a dangerous course of action for someone who didn't truly believed in the cause. Others suggest that the break with Rome was merely political manoeuvring to secure Cromwell’s own position. He remained friends with the Catholic Abbess Vernon, something which might have been unlikely if he truly believed in reformist ideas. Furthermore, he continued to own a number of traditional religious items and images, and still seemed to believe in the power of saints and indulgences.

Furthermore, he continued to own a number of traditional religious items and images, and still seemed to believe in the power of saints and indulgences. Elton suggests a half-way point, that he was quietly religious and relied more on individual connection with deity traditions, or a god or goddess. traditions, or a god or goddess. traditions, or a god or goddess. traditions, or a god or goddess. than on some rigid dogma. To Elton, his guiding principle was not the Christian god, but the nation state. It must also be remembered that in these early days of the Reformation there were no hard and fast rules, and the two labels of Catholic and protestant had not yet been clearly defined.

Elton suggests a half-way point, that he was quietly religious and relied more on individual connection with deity traditions, or a god or goddess. traditions, or a god or goddess. traditions, or a god or goddess. traditions, or a god or goddess. than on some rigid dogma. To Elton, his guiding principle was not the Christian god, but the nation state. It must also be remembered that in these early days of the Reformation there were no hard and fast rules, and the two labels of Catholic and protestant had not yet been clearly defined.

So where has his bad reputation come from? Undoubtedly, he oversaw some cruel acts: the Dissolution of the Monasteries and Anne Boleyn having already been mentioned. He also introduced harsh new treason laws, which encouraged informants and denouncements, and have led many to accuse him of having an immense spy network. They say he used this network for his own gain, but also acted quickly and efficiently against potential enemies of the state.

But was this all of his own doing? Cromwell was undoubtedly clever, had his own goals and priorities and pushed through many unpopular reforms. His king, Henry VIII, was known to be whimsical and could therefore be manipulated. However, it is not possible that Cromwell was controlling the king or dictating his actions. Henry was of sound mind and experienced in affairs of state. That Henry could have been completely unaware or disapproving of the changes implemented between 1532 and 1540 is unlikely, so the responsibility surely cannot rest with Cromwell alone.

Some of Cromwell's reputation might be put down to simple snobbery – that a commoner could raise himself so high and, worse, do a good job, did not do him many favours with the aristocracy, particularly when they were on the wrong end of his efficiency: Thomas Howard, duke of Norfolk, lost his family burial place at Thetford Priory during the Dissolution. A further reason for his emotionally cold reputation is his relationship with his family: Cromwell had a wife who died of the sweating sickness in 1528, with their two daughters dying afterwards, leaving a surviving son, Gregory, who didn’t possess the talent of the father, and towards whom Cromwell showed little affection. Surely this meant he was unfeeling and not easily touched by human sentiment? Yet this reputation seems undeserved: as MacCulloch has shown, Cromwell showed great affection towards Gregory, taking risks to further his career and status. It would also seem that he was honoured by his friends: correspondence between them was friendly and nostalgic, and he was known to throw excellent dinner parties that in particular pleased 'ladies of a certain age', as well as helping a group of rather wild young men who, MacCulloch suggests, might have reminded him of his own younger 'ruffian' self. He could also be charitable, with hundreds fed at his gates, and didn’t forget friends when they needed help.

He could also be charitable, with hundreds fed at his gates, and didn’t forget friends when they needed help.

History has not been kind to Cromwell either. Two sources used by historians in particular paint him as scheming and cold. One source is the reports of Eustace Chapuys, the Imperial resident ambassador, to whom it would seem Cromwell fed misinformation in a delicate diplomatic dance. The second source is ‘An Apology to Charles V’ written by Reginald Pole in 1538. Both of these are biased: in the first account, it would be surprising for Cromwell to be shown in an open and honest light, and in the second - an apology to a foreign, powerful, Catholic king – a scapegoat would be required, as to lay the blame for a king’s actions at the king’s door would be an act of treason.

The second source is ‘An Apology to Charles V’ written by Reginald Pole in 1538. Both of these are biased: in the first account, it would be surprising for Cromwell to be shown in an open and honest light, and in the second - an apology to a foreign, powerful, Catholic king – a scapegoat would be required, as to lay the blame for a king’s actions at the king’s door would be an act of treason.

Furthermore, as Elton has said, the 1530s was a time of revolution, spiritually, politically and socially. Cromwell was at the head of that revolution, pushing his Renaissance ideas of a nation state separate from outside influence. But it is easier, once the hardship is over, for those benefiting from the revolution to distance themselves from the necessary acts to get them there. Revolutionaries tend not to make many friends. And revolutionaries that upset those in high places tend to suffer the consequences. It was the debacle over Anne of Cleves that provided Cromwell’s enemies with the opportunity they needed: a chance to bend the king’s ear, and to turn him against Cromwell. Cromwell was arrested at a Privy Council's private advisers.'s private advisers.'s private advisers.'s private advisers. meeting, imprisoned, and shortly afterwards executed. The king never heard his pleas, and Cromwell was never given a trial. His main opponent was Norfolk, whose niece, Kathryn Howard, married Henry VIII on the same day as Cromwell’s execution. Henry later regretted having Cromwell killed, and accused his advisers of having 'upon light pretexts, by false accusations ... made him put to death the most faithful servant he ever had'. But the execution provided him with a very useful scapegoat for the nastier aspects of the religious, political and social revolution he oversaw.

But the execution provided him with a very useful scapegoat for the nastier aspects of the religious, political and social revolution he oversaw.

Things to think about

- Was Cromwell a religious man and, if so, what religion did he follow?

- Did Cromwell do anything good for England?

- How much did Henry VIII support Cromwell's reforms?

- Did Cromwell deserve his bad reputation?

- Did he deserve to be executed for treason and heresy?

Things to do

- You can visit what remains of the places Cromwell lived. There is a blue plague at 3 Brewhouse Lane, Putney, London, in the vicinity where he was born (the original cottage has long since gone). Cromwell's later home in London was at Austin Friars. It was seized in 1540 and sold to the Drapers' Company, who turned it into their hall. This was destroyed in the Great Fire of London and rebuilt, but you can still walk past it (or get married there). It's on Throgmorton Street, London EC2N 2DQ.

- Cromwell has become a figure of interest recently due to Hilary Mantel's novel Wolf Hall. Although a work of fiction, and not to be taken as anything approaching historical fact, it will provide a different idea of the man and the time.

Further reading

Diarmaid MacCulloch's new biography, Thomas Cromwell: A Life, is intelligent, witty, extremely detailed, and will undoubtedly be the go-to text for many years. Tracy Borman's biography of Cromwell, Thomas Cromwell: The untold story of Henry VIII's most faithful servant is a light and interesting read. For more scholarly works on Cromwell, the Reformation and the Tudor state, try reading the books of Geoffrey Elton, such as Reform & Renewal: Thomas Cromwell and the Common Weal (Wiles Lectures) and England Under the Tudors.