Key facts about Anne Boleyn

- Anne Boleyn was Henry VIII's second wife

- Their marriage was one of the reasons for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon and England's break from Roman Catholicism

- She was executed for adultery, treason, and incest

- We don't actually know that much about her

- Most of what we do know comes from biased accounts

People you need to know

- Catherine of Aragon - first wife of Henry VIII.

- Anne Boleyn - the second wife of Henry VIII and cousin to Kathryn Howard.

- Thomas Cranmer - proponent of the Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury.

- Thomas Cromwell - chief minister to Henry VIII after the fall of Thomas Wolsey.

- Henry VIII - Tudor king of England between 1509 and 1547.

- Thomas More - chancellor to Henry VIII prior to Thomas Cromwell and executed in 1535

- Thomas Wolsey - a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, who fell from favour in 1529.

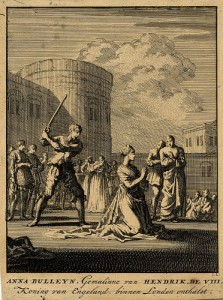

Anne Boleyn was executed on 19 May 1536, just three years after becoming King Henry VIII's second wife. She has gone down in history as an adulteress and as someone who looked somewhat odd: legend says that she had six fingers and a wen, or lump, on her neck. For the wife of a king, very little is known about Anne Boleyn: we don't even know the year in which she was born. If she kept a diary or detailed correspondence, then this has been lost, and few of her trial records survive. This means that historians have to rely on secondary sources to find out more about her, and much of this is biased. Furthermore, there are few accounts of her which are contemporary with her life: most were written several decades after her execution. There is also only one confirmed contemporary image of Anne: a medal held by the British Museum.

Anne's early life

Anne was born somewhere between 1501 and 1507, in one of her family's homes. She came from an interesting family: her great-great-grandfather was a hatter who found himself in front of manorial courts for a number of minor offences (such as trespass and taking water from the manor without payment). But not all her family were from humble origins: she was also descended from the relations of the twelfth-century saint Thomas Becket, as well as being connected with the Howards (including Kathryn Howard).

She came from an interesting family: her great-great-grandfather was a hatter who found himself in front of manorial courts for a number of minor offences (such as trespass and taking water from the manor without payment). But not all her family were from humble origins: she was also descended from the relations of the twelfth-century saint Thomas Becket, as well as being connected with the Howards (including Kathryn Howard). Her sister, Mary, was rumoured already to have borne an illegitimate son by Henry VIII before Anne and Henry married, and rumours said there might also have been an affair with Anne’s mother. Henry always denied this, saying 'never the mother', yet the suggestion remained that Anne may have been Henry’s daughter (which would have been possible only if she had been born in 1507 rather than 1501, when Henry was 10).

Her sister, Mary, was rumoured already to have borne an illegitimate son by Henry VIII before Anne and Henry married, and rumours said there might also have been an affair with Anne’s mother. Henry always denied this, saying 'never the mother', yet the suggestion remained that Anne may have been Henry’s daughter (which would have been possible only if she had been born in 1507 rather than 1501, when Henry was 10).

Anne spent much of her younger years on the Continent, being placed first in the Low Countries (1513) and then in France (1514). Here she learnt courtly behaviour and French, as well as skills such as music and dancing. When she returned to England in 1522-3, she caused a scandal with a secret engagement to Henry Percy, which forced Cardinal Wolsey to step in and order them both from court. When she returned three years later, it was as maiden of honour to Catherine of Aragon and some historians have suggested this is when the relationship between Anne and Henry VIII began.

When she returned three years later, it was as maiden of honour to Catherine of Aragon and some historians have suggested this is when the relationship between Anne and Henry VIII began.

Marriage

Anne and Henry's courtship was likely to have been a long one, although like many other things about Anne, we don't know the nature of the relationship nor the intentions of either party. Some have suggested that Henry viewed Anne as another potential mistress, but she held out for marriage. Others have argued the opposite, that Anne was the lusty one and that Henry held her back as he wanted her for a wife.

have argued the opposite, that Anne was the lusty one and that Henry held her back as he wanted her for a wife. The attraction seems to have been strong on both sides though, as they married in secret in November 1532,

The attraction seems to have been strong on both sides though, as they married in secret in November 1532, two months before their official wedding in late January 1533. Both of these weddings took place before Archbishop Cranmer had annulled Henry’s first marriage. The result of this early union, Princess Elizabeth, was born on 7 September 1533.

two months before their official wedding in late January 1533. Both of these weddings took place before Archbishop Cranmer had annulled Henry’s first marriage. The result of this early union, Princess Elizabeth, was born on 7 September 1533.

How big a part Anne played in court intrigue and the divorce of Catherine of Aragon is again something we don't know. It is possible that the divorce and break from Rome were entirely Henry's idea, and one of the reasons given was that his match with Catherine was obviously not blessed by God, as she had not given him a male child. Whether Anne spent time discussing Reformist ideas with him, and helped him to construct his arguments against Catherine of Aragon is not known, but Anne was much more swayed by Reformist ideas than was Henry who, until the last, upheld many Catholic doctrines, including the insistence on the chastity of priests, his belief of the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, and that belief should be coupled with acts of charity. Anne's opinions were so much more radical than Henry's that some historians, such as Eric Ives, have seen Anne's Protestantism as not just central to her life, but also to her death.

It is unlikely that religion was the only thing the couple disagreed upon. At times, particularly in the early days of their marriage, they were blissfully happy, infatuated with each other and spending as much time as possible together. Yet they were both spirited, strong-willed people, who 'were direct with each other, got angry, shouted, sulked, got jealous'. As G.W. Bernard states, they had 'a tumultuous relationship of sunshine and storms'.

Following the birth of Elizabeth, Anne miscarried at least once: a male child in 1536. Given the fate of Catherine of Aragon, this was a serious situation for Anne. Having failed in her duty to provide a live male heir, she was losing her husband. As early as February 1536, the court was noticing Henry's courtship of Jane Seymour, and by April rumours were circulating that Anne would soon be replaced.

Given the fate of Catherine of Aragon, this was a serious situation for Anne. Having failed in her duty to provide a live male heir, she was losing her husband. As early as February 1536, the court was noticing Henry's courtship of Jane Seymour, and by April rumours were circulating that Anne would soon be replaced.

Downfall

On 2 May 1536, Anne was arrested on the charge of high treason - discussing the death of the king - and committing adultery with her brother and four other men from the court, three gentlemen and a commoner. It is highly unlikely that the charges of adultery were true: dates and places did not add up and, unless rumours of witchcraft were true, there was very little chance of her being in two places at once. However, as a smart woman she knew her likely fate if she did not produce a male child. Perhaps then, as Bernard suggests, she may have taken a lover to conceive a son and protect her position at court. Anne went to her grave denying the accusations, as did four of the five men charged with being her lovers.

However, as a smart woman she knew her likely fate if she did not produce a male child. Perhaps then, as Bernard suggests, she may have taken a lover to conceive a son and protect her position at court. Anne went to her grave denying the accusations, as did four of the five men charged with being her lovers.

So why accuse Anne of adultery at all? Eric Ives suggests that it was the easiest way of getting rid of a woman who was upsetting powerful people at court, particularly Thomas Cromwell. Ives suggests that Anne, as a devout reformer, wished to send the proceeds from the Dissolution of the Monasteries to good causes. Cromwell, as less of a pious man, wanted to protect his own interests. We know that the trial was for show and just the notion of her discussing the King’s death would have been enough excuse to execute her. Were the charges of adultery there to make the other charge stick? Some historians - notably Retha Warnicke - think the adultery charges are more central, and linked with the ‘monstrous birth’ which Anne suffered in January 1536. Deformed children were viewed by contemporaries as punishment from God for sinful parents and, if this miscarriage had indeed been that, Henry would want to distance himself from any charge of sinfulness. As Warnicke says, ‘By having her accused of adultery with five men in the two years preceding the birth, Henry made it virtually impossible to identify him as its father. Only a tragedy like this would have led him to besmirch his honour with a public admission that five men had cuckolded him.’

Deformed children were viewed by contemporaries as punishment from God for sinful parents and, if this miscarriage had indeed been that, Henry would want to distance himself from any charge of sinfulness. As Warnicke says, ‘By having her accused of adultery with five men in the two years preceding the birth, Henry made it virtually impossible to identify him as its father. Only a tragedy like this would have led him to besmirch his honour with a public admission that five men had cuckolded him.’

However, the report of the deformed birth comes from a Catholic priest and was written in 1585, almost 50 years following Anne’s execution. This is also the first report to contain the idea that Anne was physically deformed. In a time when physical beauty was seen as an outward reflection of piety and goodness, deformity was seen as an outward sign of evil. It is possible the report was written to draw these conclusions about Anne and therefore her daughter, Elizabeth. No contemporary of Anne’s mentioned any deformity, and the fact that her lovers included Henry Percy and Henry VIII would suggest she was, at least, attractive. If this part of the report cannot be trusted, then why should the other part concerning the monstrous birth? Perhaps Henry just wanted her out of the way as quickly as possible in order to pursue his next object of affection, Jane Seymour, and to secure a male heir.

Things to think about

- How much do we really know about Anne Boleyn?

- What was Anne and Henry's early relationship like?

- What role did pregnancy and miscarriage have in Anne's downfall?

- Were the accusations against Anne true?

- What was Anne's character like?

Things to do

- The National Trust property of Blickling Hall in Norfolk is on the site of one of the family's properties, which might have been where Anne was born. The original manor house no longer exists, but the headless ghost of Anne is still said to wander the grounds on the anniversary of her execution, 19th May. Find out more about visiting Blickling Hall here.

- Hever Castle in Kent was Anne's childhood home. After her downfall, it was seized from the Boleyn family and eventually given to Henry's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. You can find out more information about Hever Castle and buy tickets here.

- Anne was imprisoned, publicly executed (the first English queen to be so) and buried within the walls of the Tower of London. Her ghost is also said to haunt the Queen's House, although this was built after her death. Our review on visiting the Tower of London can be found here and you can find out more information and buy tickets here.

Further reading

There are four historians whose books will provide a firm introduction to theories about Anne Boleyn. These are: Retha Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII. G.W. Bernard, Anne Boleyn: Fatal Attractions. Eric Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Alison Weir, The Lady In The Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn.