Key facts about Stonehenge

- The area around Stonehenge has been in use for 10,000 years

- The actual stone circle is just a small part of the Stonehenge landscape

- We still don't know how Stonehenge was built

- We still don't know what it was used for, although ritual and social gatherings seem likely

People you need to know

- Aurelius Ambrosius - a semi-legendary fifth century British king, who won against the Anglo-Saxons. He came to be known as King Arthur's uncle.

- Hengist - an Anglo-Saxon warrior who came to Britain as a mercenary and went on to settle there.

- Henry of Huntingdon - twelfth century historian and Archdeacon of Huntingdon.

- Merlin - legendary magician who is supposed to have aided King Arthur.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth - twelfth century Welsh cleric and chronicler, who wrote extensively about the kings of England and King Arthur.

- Diodorus Siculus - first century BCE Sicilian Greek historian.

- William Stukeley - eighteenth century clergyman, antiquarian and pioneer archaeologist.

- Uther Pendragon - legendary king and father of King Arthur.

Stonehenge is a famous, but little understood, stone circle just outside Amesbury in Wiltshire. It is also more than just a stone circle, with a ritual landscape spreading out from it in every direction. Within this landscape, there are a number of other earthworks, cursuses, timber circles, henges, ditches, and long and round barrows and were very common in the early Bronze Age. They continued to be built up to and including Anglo-Saxon times.'. See 'The Chronology of the Stone Age'. and were very common in the early Bronze Age , which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.. They continued to be built up to and including Anglo-Saxon times.. Although it is known around the world, and is a UNESCO world heritage site, no-one really knows who built it, why they built it, how they built it, or what it was used for. Nor do we know whether this changed over time. What we do know is that the area around Stonehenge has been used for a very long time. We also know that it took a long time and a lot of hard work to build it. It must have been important. But why?

, which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.. They continued to be built up to and including Anglo-Saxon times.. Although it is known around the world, and is a UNESCO world heritage site, no-one really knows who built it, why they built it, how they built it, or what it was used for. Nor do we know whether this changed over time. What we do know is that the area around Stonehenge has been used for a very long time. We also know that it took a long time and a lot of hard work to build it. It must have been important. But why?

Stonehenge in the Mesolithic, running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The Chronology of the Stone Age'.

Prehistorians used to think Stonehenge started being used at the very end of the Neolithic, somewhere between 3000 BCE and 2500 BCE. However, recent discoveries have pushed this date back by several thousand years. At some point in the Mesolithic, as the ice retreated and warm days - and therefore plants and animals - returned, weathering and soil accumulation worked to turn some naturally occurring cracks in the chalk of Salisbury Plain into something deeply special. As a team of archaeologists rediscovered in 2008, these natural cracks align perfectly with the NE-SW direction of the Avenue in the Stonehenge landscape, and of the rising and setting of the sun at the solstices. It is likely that the first people to walk across Salisbury Plain after the last ice age not only noticed this alignment, but also the way plants filled the lines of dark soil that collected in the fissures, coming to life in summertime and becoming dark and bare in winter. This symbolism likely helped to inspire, and then cement, the idea of the Stonehenge landscape as special.

Just two miles to the east of Stonehenge, there is evidence of considerable, sustained habitation at Blick Mead from about 8000 to perhaps 4000 BCE. By 2018, over 30,000 worked flints have been found at the site, along with fragments of animal bones from megafauna like aurochs. The beauty of this site is not just the fact that it has remained relatively undisturbed for millennia, preserving much more than is often the case, but that it lends weight to theories about the social and community lives of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. That aurochs were hunted - when the carcass of one could feed hundreds - suggests there were big meetings at Blick Mead, and this is supported by specific finds that came from all over Britain, including from Kent and Yorkshire.

The beauty of this site is not just the fact that it has remained relatively undisturbed for millennia, preserving much more than is often the case, but that it lends weight to theories about the social and community lives of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. That aurochs were hunted - when the carcass of one could feed hundreds - suggests there were big meetings at Blick Mead, and this is supported by specific finds that came from all over Britain, including from Kent and Yorkshire.

Three or four very large postholes have been found in the old visitor car-park, which, thanks to carbon dating and pollen analysis, have been dated to somewhere between 8500 BCE and 7650 BCE. Although archaeologists tend to say things were used for ritual and ceremony when they don’t understand them, these postholes suggest that the area had spiritual importance as far back as the Mesolithic. We can say there was continuity in the use of the site through to the Neolithic and later, which might also suggest continuity of people.

Although archaeologists tend to say things were used for ritual and ceremony when they don’t understand them, these postholes suggest that the area had spiritual importance as far back as the Mesolithic. We can say there was continuity in the use of the site through to the Neolithic and later, which might also suggest continuity of people. . system of beliefs in Britain and Gaul.), and the continued use of the site on its own does not guarantee continuity of people. It also shows that spirituality in the Mesolithic was developed and organised enough to build a monument.

. system of beliefs in Britain and Gaul.), and the continued use of the site on its own does not guarantee continuity of people. It also shows that spirituality in the Mesolithic was developed and organised enough to build a monument.

Stonehenge in the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age

The Stonehenge we know today started as a circular earthwork enclosure, dug about 2950 BCE, with a circle of pits just inside the bank. . Cattle skulls and jaws found by the entrances are at least two centuries older than the circle, suggesting they were moved from elsewhere and were important.

. Cattle skulls and jaws found by the entrances are at least two centuries older than the circle, suggesting they were moved from elsewhere and were important.

The henge and circle went through a number of stages of remodelling following the first phase. At some point before any stones arrived, wood was used to form a circle. Bluestones, which stood upright, were set in an arc in the centre of the enclosure a couple of centuries later, before they were remodelled

before they were remodelled and the famous sarsens added to Stonehenge around 2500 BCE.

and the famous sarsens added to Stonehenge around 2500 BCE.

Stonehenge since the Bronze Age

Stonehenge continued to be built and rebuilt until at least 1500 BCE. This shows that it was still important within the community, and still in use. The monument is often linked with the Druids (the name given to people practising an Iron Age system of beliefs), although they came after it was built.

This shows that it was still important within the community, and still in use. The monument is often linked with the Druids (the name given to people practising an Iron Age system of beliefs), although they came after it was built. But this doesn't mean they didn't use it, and Iron Age finds around the site suggest that they were aware of it. Some think there are references to Stonehenge in classical texts, particularly one written by the Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who wrote in the first century BCE. Basing his comments on earlier, and now lost, texts, Siculus mentions a temple shaped like a ball in which Apollo was worshipped.

But this doesn't mean they didn't use it, and Iron Age finds around the site suggest that they were aware of it. Some think there are references to Stonehenge in classical texts, particularly one written by the Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who wrote in the first century BCE. Basing his comments on earlier, and now lost, texts, Siculus mentions a temple shaped like a ball in which Apollo was worshipped.

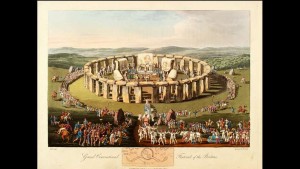

The first time Stonehenge was definitely recorded in writing was as one of the four wonders of England in the twelfth century by Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon. Writing in the same century as Henry of Huntingdon, Geoffrey of Monmouth, the famous chronicler, weaved Stonehenge into his magical story of Britain. He said that it was built by the fifth century kings Aurelius Ambrosius and Uther Pendragon with the help of Merlin to commemorate British nobles killed by Hengist and the Saxons. This story, with varying degrees of scepticism, was taken up by authors until the Stuart era, and the first recorded tourist visit took place in 1562. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several more scientific approaches were published, most notably by William Stukeley in 1740, when it became associated with the Druids and later with human sacrifice. It remained in private hands until it was bought at auction in September 1915 by a Mr Chubb for £6,000 as a gift for his wife. His wife didn't want it, so he gifted it to the nation. Since then, it has been ‘restored’ by government and charitable organisations, and the Stonehenge we now see as we drive down the A303 isn't what we would have seen 100 years ago. Access to it remains in question, and it is often under threat from building projects and roadworks.

How was Stonehenge built?

The large sarsen stones, weighing up to 45 tons each, were quarried 18 miles from Stonehenge, in the Marlborough Downs. While the quarrying and transporting of these stones is impressive, they do not provide the riddle that the bluestones present. These bluestones, each weighing between two and three tons, come from the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire, Wales, about 160 miles from Stonehenge. So, one big question about Stonehenge is ‘how did the stones even get there?’

So, one big question about Stonehenge is ‘how did the stones even get there?’

Human transportation theory

The most appealing idea is that the stones were sourced from the Preseli Hills by people with a vision for Stonehenge, and the thought that the bluestones were brought such a distance by human hand adds to the magic and mystery of the place.

When Stonehenge was built, transport across land was difficult and limited to foot. Limited technology – including the lack of wheeled transport – presented huge problems in the transportation of heavy items, and it would have been almost impossible to carry such weights over long distances by land. The other option would have been transport by boat. So, were the stones loaded onto rafts on the South Wales coast, taken along the coast of Wales and then up the Bristol Channel, followed by a journey along the narrow rivers of the Wylie and the Avon, then taken two miles across land?

Limited technology – including the lack of wheeled transport – presented huge problems in the transportation of heavy items, and it would have been almost impossible to carry such weights over long distances by land. The other option would have been transport by boat. So, were the stones loaded onto rafts on the South Wales coast, taken along the coast of Wales and then up the Bristol Channel, followed by a journey along the narrow rivers of the Wylie and the Avon, then taken two miles across land?

Aubrey Burl has suggested that the inhabitants of landlocked Wiltshire probably weren't capable of taking such a difficult journey by sea. Originally, the site of the stones was thought to be on the side of the hills closest to the sea, which would have made it easier to transport them downhill to the Pembrokeshire coast. However, new work using chemical analyses has shown that the actual site of most of the stones is on the landwards side of the hills. Not only, then, would people have had to transport them to Wiltshire, but they would also have had to drag them up and down the Preseli Hills. The problems with this situation have led people, such as Geoffrey of Monmouth, to suggest that they were moved by magic.

However, as Francis Pryor has pointed out, pondering the technicalities of moving the stones might, in fact, be missing the bigger picture. The stones were special and the very act of moving them was also significant. Difficulty might not, therefore, have been a deterrent: in more recent times, people have willingly undertaken long and hazardous journeys on pilgrimage, so why should this be any different? Ease of transportation was not necessarily the primary concern. Recent fieldwork has backed this theory up. It now seems that the stones had once formed a stone circle in Wales, and they were painstakingly moved overland to be reconstructed on Salisbury Plain. They already had a special significance, and this is why they were used: convenience was not part of the equation.

Glacial erratics

Geologists have also questioned the human transportation theory and many think the stones were carried to Wiltshire as glacial erratics (large boulders carried sometimes hundreds of miles across land by ice). Most stone circles are made from stones found locally, so it would make sense for the same to be true of Stonehenge. This helps to explain why not all bluestones are the same (they are a mixture of different sorts of dolerites and other stones), and not all of them came from the same ‘quarry’ (although most did come from the Preseli Hills).

But the glacial erratic theory still presents some questions. We don’t know which glacier could have moved them – it is unlikely that it was during the Devensian ice age experienced by Britain. It lasted from c.90000BP until 11600BP (or 9600BCE). See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'., as the last glacial maximum (LGM) didn't reach far enough south, and even the Anglian ice sheet may not have been enough. If the erratics were picked up by an Irish glacier, then why is the geographical origin of them not more widely spread, and why are there not more erratics in the area today? One place where the erratics could have been found was near Stanton Drew stone circle in Somerset, yet no erratics have been used in that circle. Also, the builders of Stonehenge have already shown they were willing to travel for the right stones by using those from the Marlborough Downs, 18 miles away. If people were willing to transport something weighing 45 tons for that distance, then surely they would be willing to transport something weighing just 5% of the sarsen stones a proportionately smaller distance? This is an argument that seems destined to continue, until definitive proof is found (if it ever will be). At the moment, the question seems to split archaeologists and geologists, although the latter are now helping archaeologists to search for quarries in the newly proposed area. Even if the geologists prove right, and the bluestones are erratics, the feat of moving both the sarsens and the bluestones, is still considerable.

Who built Stonehenge?

One thing the henge does tell us is about is the society that built it. Prehistorian Paul Bahn puts the time taken to build Stonehenge at 30 million man hours. It therefore must have been a community effort. It means the people who built it had time to spare, or at least could find the time, so their lives weren't taken up with subsistence and toil. Their farming systems were advanced enough to have the food surpluses to take time away from the fields, as well as to feed those working on Stonehenge. The community was also large enough to be able to put the manpower into building it, as this level of sourcing, transporting and building could not have been done by a small group alone. Some people have suggested that slaves were used. While we don’t know for sure, this seems unlikely: we already know that it was used as a focal point for the community, and this would probably have included the building of it. For such an important site, it would be unlikely for the organisers to entrust its building to those who were outside the community, and no evidence of slavery has been found at the site (such as slave chains).

The other thing we know about the society that built Stonehenge is that they were organised. They could organise every aspect, including the actual people who built it. The task of finding, transporting and building the stone circle would be difficult even by today’s standards. This has led many to believe there must have been a hierarchical society, with someone – or a group of people – at the top to direct the task. Whether this was a political or religious leader of the sort we have today, or whether it was a group of elders, or others, there must have been someone with the vision and capability to bring it to life. Furthermore, there must have been specialists, experts who knew about the sky, the stars, the movements of the sun and moon, as well as those who had a deep understanding of design and engineering. It was no ‘backwards’ society that built Stonehenge. Rather it was a well organised, expert, large group of individuals who had the knowledge and determination to complete the task.

This has led many to believe there must have been a hierarchical society, with someone – or a group of people – at the top to direct the task. Whether this was a political or religious leader of the sort we have today, or whether it was a group of elders, or others, there must have been someone with the vision and capability to bring it to life. Furthermore, there must have been specialists, experts who knew about the sky, the stars, the movements of the sun and moon, as well as those who had a deep understanding of design and engineering. It was no ‘backwards’ society that built Stonehenge. Rather it was a well organised, expert, large group of individuals who had the knowledge and determination to complete the task.

What was the purpose of Stonehenge?

We still don’t know what Stonehenge was used for. Although we know certain things about the stones, which help us decide which uses are most likely, everything else is guesswork. As the area was in use for millennia, it is possible that it had many different uses, and as the arrangement of the stones changed, so might their use.

Calendar

The sarsen stones line up with the setting sun on the winter solstice and the rising sun at summer solstice, and one of the thirty sarsen stones is narrower and shorter than the others. This gives a grand total of 29.3 sarsens, which is the number of solar days in a lunar month.

Given its alignment with the sun (and moon), Stonehenge could have been used as a sort of calendar. The place of the sun around the monument would show the time of year, and so it could be used to record the seasons and as a diary – the position of the sun could indicate when gatherings should happen, or when other processes should start or finish.

The exactness of this alignment would have taken considerable skill and knowledge as it was done without the aid of modern technology and measuring devices: it was made with the help of expert astronomers, who knew how to place the stones, and whose knowledge would have been gained over many years. Some people have even compared the builders of Stonehenge with those of the Egyptian pyramids. But not only were they master astronomers: they also had a deep understanding of geometry and design. The design of Stonehenge is so clever that some people have suggested it was used as a giant calculator, for dating eclipses and other astronomical events.

Religion

One of the most obvious suggestions is that it was a temple, or place of religious worship, with almost every prehistorian suggesting a range of ritual practices. It would certainly seem that the site has a history of religious and ritual use, with the discovery of the huge Mesolithic posts, which Mike Allen suggests were something similar to Native American totem poles, celebrating either the place or local people’s beliefs. Mike Parker Pearson has suggested that the stones were brought to Wiltshire to represent the ancestors of the people who built the monument, and that it was a temple to the history of the tribe. Timothy Darvill suggests that the five great sarsen trilithons (each trilithon – meaning ‘three stones’ – being made of two uprights and one placed horizontally across the top) might have represented the gods of the time. The henge at nearby Durrington Walls also has five shrines, so he thinks that the number five was important. Religious belief during the Neolithic and Bronze Age seems to have focused on the sky and the seasons, and the alignment of the stones, as well as their size, could support the idea of a temple to the sky.

Timothy Darvill suggests that the five great sarsen trilithons (each trilithon – meaning ‘three stones’ – being made of two uprights and one placed horizontally across the top) might have represented the gods of the time. The henge at nearby Durrington Walls also has five shrines, so he thinks that the number five was important. Religious belief during the Neolithic and Bronze Age seems to have focused on the sky and the seasons, and the alignment of the stones, as well as their size, could support the idea of a temple to the sky.

All of these theories might be true, or none of them. Spirituality could include worship of the ancestors, the land and nature, the sky, and magic such as healing. Worship of one wouldn’t exclude worship of the others. It is also likely that religious belief was not separate from other parts of daily life, as is often the case today, and Stonehenge may well have been important both spiritually and in other ways.

Healing

Timothy Darvill also suggests that Stonehenge started as a centre for healing. This is based on the (false) belief that the bluestones originally came from an area with natural springs (water is often associated with healing and with the gods), as well as the long-standing oral tradition which says the stones have healing properties. Pieces of the bluestones were chipped off and taken elsewhere almost from the moment they arrived at the site, suggesting that people wanted to take the healing properties of the stones with them. This could, however, easily be for another reason: wanting an amulet, perhaps, or as a sign that they belonged to a particular group, either geographically or through training or belief. Perhaps it was nothing as grand or symbolic: perhaps people just took pieces as a souvenir – rather like we take home souvenirs from places we’ve visited today. Whatever the reason for it, it would still show that the site was important enough for people to want to take bits of it away with them.

Burials

The idea of a centre for healing could explain the surrounding burials, of which there were many. Cremated bodies have been found dating to between c.3000-2500 BCE and burials continued at the site for centuries afterwards. The surrounding landscape is littered with both Neolithic long barrows and Bronze Age round barrows. Many of the 50 sets of older cremations found are of men, and Timothy Darvill thinks these may be the remains of an important line of people, such as rulers, shamans or medicine men.

Some of the burials are particularly interesting: the man known as the Amesbury Archer came from a long way away. Chemical analysis of his teeth shows that he was born in Bavaria, but eventually settled in the area. His bones show that he suffered injury: did he originally come to the area seeking a cure, or was there another reason for him, and others like him, to visit and maybe live in the area? Perhaps the burials have less to do with any healing properties of the stones, and more to do either with religion or the community.

Perhaps the burials have less to do with any healing properties of the stones, and more to do either with religion or the community.

Community life

Given that for one reason or another Stonehenge was important to those who built it and their descendants, it must also have had an important social function. What this included is, like all other things about Stonehenge, a guess. However, we do know that people gathered for feasting and for disposing of their dead. It might also have been used for healing and it was definitely used to mark important dates in the year. As such, it would have provided a focal point for a community and beyond, where societal and personal bonds would have been made, renewed and broken.

Things to think about

- Who was Stonehenge built and used by?

- How was Stonehenge built?

- What was the purpose of Stonehenge?

- How did the use of Stonehenge change over time?

Things to do

- Visit Stonehenge (entrance is free to English Heritage and National Trust members). You can find out more information about it here. See our review of it here.

- Stonehenge at Midsummer can be hectic, but if you want to enjoy the celebratory feel inside the stones it is open to the public at the winter solstice. English Heritage usually publishes details.

- Take a walk around the Stonehenge landscape. There are many books and maps for walking in the area, and best of all, walking doesn't cost anything!

- Keep up-to-date with the latest theories about, and finds from, Stonehenge by searching for it in news articles.

- Think how you would move the bluestones from the Preseli Hills to the Salisbury Plains. Try to plan the journey on a map, and remember that it's very difficult to go across dry land. What technology would you use to transport them? See how difficult it is to move a heavy object (like a book) across a flat surface on rollers (such as lengths of wooden dowel, which you can buy from places like ebay). What about transporting it uphill or downhill: what are the problems you encounter? Would there be a better way of moving something heavy across land?

Further reading

There's a huge number of books on Stonehenge, some of them good, many of them terrible. It can also be difficult to find books that are properly up-to-date, as new things are being discovered all the time. One of the most prolific authors on Stonehenge, who has spent a considerable time working in the Stonehenge landscape, is Mike Parker Pearson. A good, and recent, book is his Stonehenge: Exploring the greatest Stone Age , running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools. mystery. Providing a different viewpoint, but sadly a bit outdated and technical, is Aubrey Burl's A Brief History of Stonehenge, part of the Brief Histories series.

, running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools. mystery. Providing a different viewpoint, but sadly a bit outdated and technical, is Aubrey Burl's A Brief History of Stonehenge, part of the Brief Histories series.