Key facts about death in the Stone Age

- How humans dealt with death in the Stone Age changed over time and place

- The way our ancestors dealt with death can tell us a lot about the people, the way they thought and their society

- We don't know when humans started thinking about death and what came afterwards

The way people deal with their dead can tell us a lot about them. It can tell us if they can think on an abstract level, whether they understand the concept of death (that it is final and irreversible rather than thinking simply ‘that person was there, and now they’re not’), and that they can think deeply about a person, their life and death (that they can feel grief, love and respect). It suggests that a people might – or might not – have beliefs about what happens when they die, and how this should be approached. Death can tell us about a society’s ability to think, feel, believe and act. The ability to mark death and address it as a concept has always been considered something that sets Homo sapiens apart from our predecessors, although mounting evidence is disputing this. The way humanity deals with death has changed over time. Outwardly, the way bodies are buried, cremated, or otherwise disposed of has changed, sometimes one process being in fashion, sometimes another. But it is the beliefs and thoughts which determine these practices that make the subject of death and burial so interesting.

Palaeolithic

Lower Palaeolithic

People think our distant ancestors did not mark the passing of kith and kin. There was no evidence of burials, let alone grave goods or markers and so we always assumed early humans had no concept of death as we would understand it today. The lack of deliberate burials led many to question the ability of our early ancestors to think in the abstract, and we have therefore made assumptions about their development and intellect. Until now. At Sima de los Huesos (the Pit of Bones) in Atapuerca, Spain, bones have been found which date from 430,000 years ago, at a site which shows no signs of domestic use. The Pit of Bones is just that – it is a chamber at the bottom of a 13m shaft. Within it were found bones of at least 28 hominins, along with a number of cave bears and a red quartzite handaxe, known as ‘Excalibur’. Some archaeologists believe this was a place of deliberate burial, with the handaxe – a beautiful piece that would have had considerable worth – being a deliberately placed grave good. Other archaeologists think the bones got there either through accident (such as the cave collapsing) or were moved by flood water. However, if the burial theory is correct, this would push the date of the first confirmed deliberate burials back by 200,000 years and challenge a lot of presumptions about our ancestors.

Spain, bones have been found which date from 430,000 years ago, at a site which shows no signs of domestic use. The Pit of Bones is just that – it is a chamber at the bottom of a 13m shaft. Within it were found bones of at least 28 hominins, along with a number of cave bears and a red quartzite handaxe, known as ‘Excalibur’. Some archaeologists believe this was a place of deliberate burial, with the handaxe – a beautiful piece that would have had considerable worth – being a deliberately placed grave good. Other archaeologists think the bones got there either through accident (such as the cave collapsing) or were moved by flood water. However, if the burial theory is correct, this would push the date of the first confirmed deliberate burials back by 200,000 years and challenge a lot of presumptions about our ancestors.

Recent finds in a hard-to-reach cave in South Africa of at least 15 human-like skeletons called Homo naledi (after the cave in which they were discovered) show signs of having been deliberately placed. There is no evidence of catastrophe to take the bodies to the cave, nor water or other sediments that would indicate a flood. In addition, apart from the bones of an owl, there are no animal bones in the cave, and no predator has chewed on or clawed at the bones. The cave was therefore probably inaccessible to all but the most determined, and the motivation to dispose of the bodies there must have been strong. If these are burials, they could indicate that there was the concept of death and burial, as well as provide evidence of planning.

of at least 15 human-like skeletons called Homo naledi (after the cave in which they were discovered) show signs of having been deliberately placed. There is no evidence of catastrophe to take the bodies to the cave, nor water or other sediments that would indicate a flood. In addition, apart from the bones of an owl, there are no animal bones in the cave, and no predator has chewed on or clawed at the bones. The cave was therefore probably inaccessible to all but the most determined, and the motivation to dispose of the bodies there must have been strong. If these are burials, they could indicate that there was the concept of death and burial, as well as provide evidence of planning.

Even with these finds, let alone the prospects of more, it must be remembered that for hunter gatherers, who were constantly on the move, burial in a fixed position might not have been the best way of honouring or remembering the dead. We have to be careful that our own practices don’t make us overlook different practices from different times and peoples.

Middle Palaeolithic

Neanderthals

As we enter the Middle Palaeolithic, we begin to find more signs of deliberate disposal of the dead. At first, early Neanderthals seem to have ‘processed’ bodies of the dead, by defleshing and disarticulating them (the removal of the flesh from the bones, and splitting the bones at their joints). This practice has led many to accuse Neanderthals of cannibalism, which we will address in more detail below. The first likely deliberate burials so far found in Britain are of at least five early Neanderthals (dating to about 230000 BP) in Pontnewydd Cave in Wales. By the transition between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, Neanderthals have shown signs of careful burials for many in their community, from infants through to the elderly.

This practice has led many to accuse Neanderthals of cannibalism, which we will address in more detail below. The first likely deliberate burials so far found in Britain are of at least five early Neanderthals (dating to about 230000 BP) in Pontnewydd Cave in Wales. By the transition between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, Neanderthals have shown signs of careful burials for many in their community, from infants through to the elderly. This might suggest that their society was more egalitarian than some others, as they seemed to show no distinction according to age.

This might suggest that their society was more egalitarian than some others, as they seemed to show no distinction according to age. There are no confirmed grave goods in Neanderthal burials (grave goods show either concepts of the afterlife or concepts of ownership, both of which require abstract thought), but there seems to be deliberate arrangement of bodies in modified graves.

There are no confirmed grave goods in Neanderthal burials (grave goods show either concepts of the afterlife or concepts of ownership, both of which require abstract thought), but there seems to be deliberate arrangement of bodies in modified graves. There are also a few possible examples of limestone blocks used as grave markers either within or on top of graves, although it is difficult to prove they were put there on purpose. So, did the Neanderthals have processes for dealing with their dead? The general agreement is that they did, at least some of the time. There is less agreement though on what that means about the way they thought and whether or not they were ‘intelligent’. Homo sapiens like to think of themselves as special.

There are also a few possible examples of limestone blocks used as grave markers either within or on top of graves, although it is difficult to prove they were put there on purpose. So, did the Neanderthals have processes for dealing with their dead? The general agreement is that they did, at least some of the time. There is less agreement though on what that means about the way they thought and whether or not they were ‘intelligent’. Homo sapiens like to think of themselves as special.

Homo sapiens

Anatomically modern humans are still considered by some to be the first people deliberately to practice burial. Whether or not this was the case, many of these burials seem to be more advanced than those of their predecessors. The first Homo sapiens burials in Europe are actually at the ‘gates of Europe’, in Israel,

are still considered by some to be the first people deliberately to practice burial. Whether or not this was the case, many of these burials seem to be more advanced than those of their predecessors. The first Homo sapiens burials in Europe are actually at the ‘gates of Europe’, in Israel, and date from about 100,000 years ago. They do seem more complicated than known Neanderthals burials, with the bodies being carefully placed in position, and with grave goods (mainly of animal bones) included.

and date from about 100,000 years ago. They do seem more complicated than known Neanderthals burials, with the bodies being carefully placed in position, and with grave goods (mainly of animal bones) included.

But it is not until the Upper Palaeolithic that we start to see large numbers of complex burials. The earliest in Britain, and the most famous, is known as the Red Lady of Paviland. This skeleton was found in Goat’s Cave, on the Gower Peninsula in Wales by William Buckland in 1823. Buckland was committed to a history of the world as described in the Bible, and this led him to false conclusions. He thought the skeleton was contemporary with the Roman invasion (believing the nearby Iron Age hillfort to be a Roman military camp) and a female prostitute, despite the fact that the skeleton was found with the bones of extinct animals. Actually the skeleton was male and died about 33,000 years ago. At the time of his death the Red Lady was somewhere between 25 and 30 years old, and otherwise in good health, standing at about 5’8 and weighing about 11 stone. The Red Lady was covered in red ochre (hence the name) and was found with a mammoth ivory bracelet and a perforated periwinkle pendant, numerous seashells and broken ivory rods.

He thought the skeleton was contemporary with the Roman invasion (believing the nearby Iron Age hillfort to be a Roman military camp) and a female prostitute, despite the fact that the skeleton was found with the bones of extinct animals. Actually the skeleton was male and died about 33,000 years ago. At the time of his death the Red Lady was somewhere between 25 and 30 years old, and otherwise in good health, standing at about 5’8 and weighing about 11 stone. The Red Lady was covered in red ochre (hence the name) and was found with a mammoth ivory bracelet and a perforated periwinkle pendant, numerous seashells and broken ivory rods. Markers were placed at both ends of the grave, and it was likely the body was buried both with clothes and shoes. The nature of the burial, suggests he was an important man. Some prehistorians, such as Francis Pryor, think he might have been a shaman, suggesting the grave goods were important ritual items.

Markers were placed at both ends of the grave, and it was likely the body was buried both with clothes and shoes. The nature of the burial, suggests he was an important man. Some prehistorians, such as Francis Pryor, think he might have been a shaman, suggesting the grave goods were important ritual items.

Mesolithic

There are few complete human skeletons found during the Mesolithic, which suggests there were few burials or other methods of disposing of the dead which would leave a trace. Barry Cunliffe thinks excarnation (defleshing) was probably frequently practised, which could account for this rarity. His opinion is backed up by the number of human remains found in shell middens (waste heaps) across the world, including in the Scottish Isles. The discoveries of these bones, which are usually only small bones or pieces of bone, have led many to believe they show signs of cannibalism, with the waste simply being disposed of. There are a number of other Mesolithic human bones that have been found in places such as Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Valley in Somerset (dating from about 14700 BP, rather than Cheddar Man, whom we will discuss shortly), which show clear signs of butchery. This doesn't mean that Mesolithic peoples practised casual or nutritional cannibalism. It might just as easily show some form of ritual disposal. Whatever the reason, it seems clear that certain ways Mesolithic people dealt with their dead are very different from how we deal with the dead today.

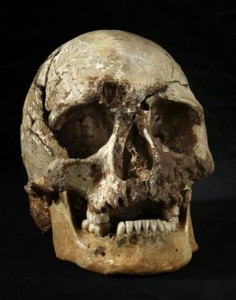

Not all ways of dealing with the Mesolithic dead were as foreign to us as defleshing, nor was the Mesolithic entirely without burials. One of the few complete skeletons of the Mesolithic, and Britain’s oldest complete skeleton, is that of Cheddar Man, found at Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Valley. He died in about 7150 BCE, when he was still in his twenties. Newspaper headlines state that he died violently, as there is a hole in his skull, but this was probably caused by bone disease or sinus infection, which would have been painful and may have killed him in the end. Another cave in the Cheddar area is Aveline's Hole in which the remains of about 70 people were found, most disarticulated but two placed whole. They all died between 8400 BCE and 8200 BCE and include men, women and children. Seven pieces of fossil ammonite were placed by the head of one, and the presence of animal teeth suggests that some of the bodies may have been adorned. In addition, red ochre was found at the site. Sadly, most of the collection was lost to German bombs in World War Two making it difficult to study them further. All we can say is that funerary customs in the Mesolithic could be complex and sophisticated.

Neolithic

As people became tied to the land, they began to view death and burial in different ways, or at least to dispose of their dead in different ways. We also begin to see differences between different areas of the country, with, for example, the west of England doing something different from the east of England.

The famous Neolithic burial chamber, the long barrow, began to appear in the south and east of Britain from about 3800 BCE and continued in use until about 3300 BCE. Bones, which had gone through some form of defleshing first, were placed in mortuaries which after a while were sealed off, either by piling mud and stones over the room, or by blocking the doorway with stone. It is possible that there was some form of ceremony in the barrow’s forecourt before, during, or after the placing of the bones. Before the barrow was closed, the skeletons of those within weren't left in peace: bones were often moved around and spread over several chambers. Pryor suggests this was because the bones of ancestors were used in marking formal social and familial alliances.

It is possible that there was some form of ceremony in the barrow’s forecourt before, during, or after the placing of the bones. Before the barrow was closed, the skeletons of those within weren't left in peace: bones were often moved around and spread over several chambers. Pryor suggests this was because the bones of ancestors were used in marking formal social and familial alliances.

Despite how common long barrows are in the landscape today, they weren't the only way of dealing with the dead. From about 3500 BCE, the practice of fiddling with the bones of the dead became less common, and single burials with bodies still intact became more so. Could this be because the idea of death changed and with it the social role of the dead? Perhaps they started to belong to a different world rather than within the living community. Some bodies never found their way into a barrow or other tomb, and many have been found that show evidence of being gnawed by dogs, suggesting that they were left out in the open. In the very far west, dolmen portals (simple rooms with capstones) and court tombs (tomb with courtyards) were most common, and all along the Atlantic coast there were passage graves. These monumental structures, sometime reaching 5m high, were most popular around 3000 BCE and had a burial chamber at the end of a decorated passage, which was often in alignment with the rising or setting sun at either the summer or the winter solstice. Other burial sites combine the eastern and western traditions, such as the roughly 175 burial mounds in the Severn-Cotswold group.

Cannibalism

We have come across possible examples of cannibalism, or at least defleshing, several times in this article, and it seems to be a common theme across time, and even across species. We know beyond a doubt that defleshing was practised for millennia, but it is harder to find out whether this was because of cannibalism or some other funerary rite. Even where cannibalism is suspected, it doesn’t mean that it was done with violence, dishonour or casually for food. There are reports of tribes in South America which consider it an extreme dishonour not to eat the flesh of their dead relatives, and they force themselves to do so, even when it makes them physically sick.

There are certain things we look for to help us decide if cannibalism, and what sort of cannibalism, was practised. The first clue is whether the body was treated in a similar way to animals that were butchered for meat, including smashing or cracking bones to get the bone marrow out. Evidence of cooking would strongly suggest cannibalism, particularly for nutrition rather than ritual. Another clue is where the bones are found: if they have been carelessly treated and put on a midden with other sorts of bones, then they could have been used as a source of food. Or not: it’s very difficult to get into the mindset of people from different times and species even without the problems of what to us is a taboo subject. When our modern western minds shy away from a subject, which to us is disgusting, it makes it even harder to understand what really happened. Archaeologist Paul Bahn says all instances of potential cannibalism have other possible explanations, such as violence or complex funerary rites. Furthermore, he says that ‘well-documented cases based on direct observation rather than hearsay or propaganda are extremely rare for historical periods.’ Basically, it is a standard trick of propaganda to paint other cultures as barbarians and cannibals. This means that a lot of anthropological evidence cannot help us decide whether or not our ancestors ate one another.

Basically, it is a standard trick of propaganda to paint other cultures as barbarians and cannibals. This means that a lot of anthropological evidence cannot help us decide whether or not our ancestors ate one another.

With so many of our early and more recent ancestors defleshing the dead, it is not possible to cover all of them. Instead, we will focus on some of the most famous cases of likely cannibalism. Homo antecessor may well have cannibalised others, judging by bones dating from 800,000 years ago found in Atapuerca. There is no evidence that human remains were treated differently from butchered animal bones also found at the site, which show cut marks and smashing.

may well have cannibalised others, judging by bones dating from 800,000 years ago found in Atapuerca. There is no evidence that human remains were treated differently from butchered animal bones also found at the site, which show cut marks and smashing. Neanderthal bones at El Sidrón in Spain, in what has been named the ‘Tunnel of the Bones’, show cut marks and smashing. This family group of 12 people, ranging from adults to infants, were alive around 48,000 years ago and show signs that they suffered from malnutrition while alive. This has led many to conclude that they were killed and eaten primarily for food, rather than ritual. Similar evidence has been found in Croatia and France.

Neanderthal bones at El Sidrón in Spain, in what has been named the ‘Tunnel of the Bones’, show cut marks and smashing. This family group of 12 people, ranging from adults to infants, were alive around 48,000 years ago and show signs that they suffered from malnutrition while alive. This has led many to conclude that they were killed and eaten primarily for food, rather than ritual. Similar evidence has been found in Croatia and France.

Homo sapiens have also shown signs of butchery and cannibalism. Remains of at least two adults, two adolescents and one three-year-old child dating to 14700 BP were found at Gough's Cave. They were defleshed at the very least, with the skulls of the bodies being used as cups.

They were defleshed at the very least, with the skulls of the bodies being used as cups. There are signs of breaking the bones apart to get the marrow, and it looks as if the tongue was also removed. It is possible that at least some of their deaths were violent, as one adult was decapitated while lying face down (although we don’t know if the person was alive at this point). Chris Stringer sees this as evidence enough for nutritional cannibalism, although others are less certain: Gough’s Cave has been dug and re-dug for over a century, many times without due care. It is quite possible that the bones were damaged by eager and unscrupulous archaeologists, while the care taken over the skull cups suggests they were held in some respect.

There are signs of breaking the bones apart to get the marrow, and it looks as if the tongue was also removed. It is possible that at least some of their deaths were violent, as one adult was decapitated while lying face down (although we don’t know if the person was alive at this point). Chris Stringer sees this as evidence enough for nutritional cannibalism, although others are less certain: Gough’s Cave has been dug and re-dug for over a century, many times without due care. It is quite possible that the bones were damaged by eager and unscrupulous archaeologists, while the care taken over the skull cups suggests they were held in some respect.

Things to think about

- How does studying death in the Stone Age help us to understand the people who lived in it?

- When did humans start dealing with their dead, and what does this say about their species and our understanding of modern humans?

- Did Neanderthals bury their dead deliberately?

- What evidence is there for prehistoric cannibalism, and what was its purpose?

Things to do

- The Natural History Museum's Human Evolution gallery has on show many of the artefacts mentioned here, including Cheddar Man, replicas of the Homo naledi skeletons and the skull cups from Cheddar Gorge. You can find out information about visiting here and see our review of it here.

- Visit Cheddar Gorge, where you can view a replica of Cheddar Man, as well as exhibitions on Stone Age life and on cannibalism. You can buy tickets online here.

- The National Museum of Wales in Cardiff has a number of finds relating to the Pontnewydd Caves and the Red Lady of Paviland, although sadly the Red Lady himself is back under lock and key at Oxford. You can find out about visiting here.

- There are thousands of Stone Age burial sites across the country. Some of the most well known, and worth a look, are those in the Stonehenge landscape, as well as the West Kennet long barrow. For those able to visit Ireland, there are some splendid passage graves in the Boyne Valley, on the east coast (although Newgrange has been meddled with to the point where it would now be unrecognisable to those who built it). However, it is likely there are burial sites which are closer to you: use megalithic.co.uk to find them.

Further reading

It is always difficult to recommend books on prehistoric Britain because they become out of date as soon as they are published. But without a shadow of doubt the best book on the market at the moment is Stringer and Dinnis' book Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story. Francis Pryor's book Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland before the Romans, although now dated, is engaging and written with passion.