Key points about William Marshal

- William Marshal was a landless younger son.

- He was almost killed when he was five, after his father risked his life for military advantage.

- William became a celebrity on the tournament circuit, making himself rich in the process.

- He served five crowned kings as a warrior and adviser, and helped negotiate Magna Carta.

- He was also named a traitor and bested Richard the Lionheart in single combat.

- William became de facto regent of England when the nine-year-old Henry III became king.

- William participated in his last battle when he was 70 years old.

People you need to know

- Arthur of Brittany - son of Henry II's fourth son, and John's rival for the throne

- Eleanor of Aquitaine - wife of Henry II and a powerful woman in her own right

- Henry II - son of the Empress Matilda and head of the Angevin Empire (including king of England) from 1154 until 1189

- Henry the Young King - the eldest son of Henry II's to survive childhood, who was crowned as Henry II's successor in 1170

- Isabel of Clare - heiress to considerable lands, who became William's wife

- King John - the youngest of Henry II's sons, and king of England from 1199 until 1216

- Louis of France - Capetian prince and son of Philip II of France

- John Marshal - William Marshal's father, a middle-ranking nobleman

- William Marshal - the 'greatest knight' who transformed himself from a younger son to one of the most important people in England

- Patrick, earl of Salisbury - an important landowner and William's uncle

- Philip II of France - Capetian king of France from 1180 until 1223, and a long-standing opponent of the Angevin Empire

- Richard I (the Lionheart) - third son of Henry II, who ruled as king between 1189 and 1199

- King Stephen - king of England between 1135 and 1154, most of which time was spent at war with his cousin the Empress Matilda in the Anarchy

William Marshal was born a younger son of a middle-ranking nobleman, from whom he inherited neither land nor title. But over a lifetime of more than seven decades, he raised himself from relatively humble beginnings, through the tournament circuit and serving five crowned kings, to become the de facto regent of England. He was the original celebrity, inspiration for films such as A Knight's Tale, and by his death was considered 'the greatest knight' in the world.

An early brush with death

William Marshal was the second son of John Marshal and John's second wife Sybil, sister to the earl of Salisbury. He was born around 1147 during the Anarchy, the civil war between Stephen and his cousin, the Empress Matilda. John Marshal's own father, Gilbert Giffard,  came to England during the first wave of the Norman Conquest or shortly thereafter. According to Domesday Book, Giffard held land in Wiltshire, and served as the royal master-marshal, an administrative post concerned with the well-being of the king's horses but which expanded to include the day-to-day running of the court. The role was inherited by William's father during the reign of Henry I, for which he paid 40 silver marks.

came to England during the first wave of the Norman Conquest or shortly thereafter. According to Domesday Book, Giffard held land in Wiltshire, and served as the royal master-marshal, an administrative post concerned with the well-being of the king's horses but which expanded to include the day-to-day running of the court. The role was inherited by William's father during the reign of Henry I, for which he paid 40 silver marks.

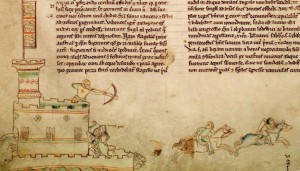

John Marshal used the civil war to increase his own power and fortune but in 1152 he pushed his luck too far when he built a castle at a crossroads with the aim of controlling both east-west traffic and that between Oxford and Winchester.  Stephen laid siege to the castle and, in order to give himself more time, John spoke of surrender and gave the five-year-old William as hostage for his word.

Stephen laid siege to the castle and, in order to give himself more time, John spoke of surrender and gave the five-year-old William as hostage for his word.  Perhaps John didn't care much for his son, for he immediately broke his pledge, declaring that 'he did not care about the child, since he had the anvils and hammers to forge even finer ones.'

Perhaps John didn't care much for his son, for he immediately broke his pledge, declaring that 'he did not care about the child, since he had the anvils and hammers to forge even finer ones.'  It was certainly an unusual step for John Marshal to take. As Thomas Ashbridge states, 'The use of one's children as diplomatic hostages was commonplace in western Europe; the act of forsaking a child in favour of military advantage was not.'

It was certainly an unusual step for John Marshal to take. As Thomas Ashbridge states, 'The use of one's children as diplomatic hostages was commonplace in western Europe; the act of forsaking a child in favour of military advantage was not.'  Maybe, as Stephen was considered a soft touch, willing to forgive opponents and opposed to displays of retribution, John thought it unlikely William would be killed.

Maybe, as Stephen was considered a soft touch, willing to forgive opponents and opposed to displays of retribution, John thought it unlikely William would be killed.  If so, his gamble very nearly didn't pay off. Understandably angry, Stephen ordered William to be taken to the gallows to be hanged. He changed his mind, but William wasn't spared; instead, he was to be catapulted into the castle as a very personal message to his father. William had actually climbed into the catapult before Stephen once again changed his mind. The final idea was to attach William to a siege machine while the castle was stormed, thus crushing him to death. No-one really knows why William survived, but his biographer

If so, his gamble very nearly didn't pay off. Understandably angry, Stephen ordered William to be taken to the gallows to be hanged. He changed his mind, but William wasn't spared; instead, he was to be catapulted into the castle as a very personal message to his father. William had actually climbed into the catapult before Stephen once again changed his mind. The final idea was to attach William to a siege machine while the castle was stormed, thus crushing him to death. No-one really knows why William survived, but his biographer  states it was because Stephen was charmed by the boy's innocent questions, saying that 'anyone who could ever allow him to die in such agony would certainly have a very cruel heart'.

states it was because Stephen was charmed by the boy's innocent questions, saying that 'anyone who could ever allow him to die in such agony would certainly have a very cruel heart'.  Newbury Castle eventually fell, although John Marshal escaped. William Marshal stayed with Stephen until a peace was agreed, on 6 November 1153.

Newbury Castle eventually fell, although John Marshal escaped. William Marshal stayed with Stephen until a peace was agreed, on 6 November 1153.  When William returned to his family his mother, at least, was delighted to see him.

When William returned to his family his mother, at least, was delighted to see him.

Training and capture

At 12 or 13, William left England for Normandy to be educated as a knight under William of Tancarville, his mother's relative. We know little of the six or seven years he spent there, apart from that he slept, ate and drank too much.  He finished his knightly education in 1166 when he was about 20, and soon after got a taste of battle at a skirmish in Neufchatel. His biographer states that he performed exceptionally well, but he also had much to learn: he had taken neither booty nor captives, but had himself been injured, had his armour damaged and his warhorse killed.

He finished his knightly education in 1166 when he was about 20, and soon after got a taste of battle at a skirmish in Neufchatel. His biographer states that he performed exceptionally well, but he also had much to learn: he had taken neither booty nor captives, but had himself been injured, had his armour damaged and his warhorse killed.

Before long, as the border dispute that had caused the skirmish died down, the size of the Tancarville retinue (or mesnie) reduced and Marshal was left without a warhorse or a lord to serve. Whether or not his reversal of fortune came about because of a falling out or some other personal issue, or whether it was just expediency, we don't know. But rather than returning to England, William sold his new cloak (which he had received at his knighting) to buy a packhorse and set about making his own way. Due to his kinship with the household, William was allowed to visit a tournament with the retinue, and was lent a particularly bad-tempered warhorse on which to participate. Despite this, Marshal performed well, winning four warhorses, and a number of other horses and equipment. Just as importantly, he also won the respect of his peers. William stayed on the tournament circuit for at least a year and, despite a few setbacks, made enough money to return to England as an equal to his elder brother, who had since inherited the estates and title of their father.

On his return, he sought out employment as a knight in the mesnie of his uncle, earl Patrick of Salisbury, and soon found himself returning to France with Salisbury and Henry II. The aim was to sort out some local Lusignan warriors who were trying to increase their own power and prestige – at Henry's expense – in Aquitaine. A few raids into their lands, mainly burning the crops and possessions of local peasants,  put an end to their attempts to take power, and Henry left for the north, leaving his wife Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to pacify and charm the local populace.

put an end to their attempts to take power, and Henry left for the north, leaving his wife Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to pacify and charm the local populace.

It was on one of these trips into the countryside, where Eleanor was being escorted in a leisurely manner by Salisbury, Marshal and a few other unarmoured knights, that they were set upon by the two brothers who'd led the disturbances in Aquitaine. Eleanor was quickly whisked away while Salisbury and his knights held the road. Salisbury charged, unarmoured and on a palfrey, and was killed, stabbed in the back by a lance as he tried to change horses. William, so his biographer states, went into a rage and attacked like a berserker, but was also eventually felled by a lance through his thigh, driven through a bush that was behind him. Bleeding out and unattended, he was strapped to an ass and carried away as a hostage.

It was unlikely that a ransom would be paid for William, being a lowly knight, and so William's prospects didn't seem good. He tried to tend to the wounds himself, first by ripping his own clothes and then by begging for some sacking to use as a bandage. So the story goes, at one point they visited the house of a supporter, where a lady gave William some fine bandages to dress his wounds, hidden in a loaf of bread.  Thereafter, William's wounds healed better, until he decided to take place in a rock-throwing competition with his captors. Although he managed to throw the boulder further than everyone else, his wounds re-opened and the healing process had to start again.

Thereafter, William's wounds healed better, until he decided to take place in a rock-throwing competition with his captors. Although he managed to throw the boulder further than everyone else, his wounds re-opened and the healing process had to start again.  Eventually, a message from Eleanor reached him, indicating she would be happy to pay the ransom, and he became accepted into her personal retinue: an exceptionally lucky stroke for William. No-one quite knows why she did this, although Ashbridge suggests that he had either caught her eye during his time with her, or she heard tales of his valour on the roadside and felt an obligation to him.

Eventually, a message from Eleanor reached him, indicating she would be happy to pay the ransom, and he became accepted into her personal retinue: an exceptionally lucky stroke for William. No-one quite knows why she did this, although Ashbridge suggests that he had either caught her eye during his time with her, or she heard tales of his valour on the roadside and felt an obligation to him.

Traitor, tournament champion and crusader

In 1170, Henry the Young King was crowned as the next king, although his father, Henry II, still lived.  Shortly afterwards Marshal was appointed as the Young King's tutor-in-arms and a leading member of the Young King's mesnie, possibly on Eleanor's advice.

Shortly afterwards Marshal was appointed as the Young King's tutor-in-arms and a leading member of the Young King's mesnie, possibly on Eleanor's advice.

Historians have not been kind to the Young King. In 1973, Lewis Warren described him as 'gracious, benign, affable, courteous, the soul of liberality and generosity. Unfortunately he was also shallow, vain, careless, empty-headed, incompetent, improvident and irresponsible'.  A crowned king without land, income or any real power of his own, he still had to govern while his father was in foreign lands and still had to maintain his own retinue and wife, whose dower lands were held by Henry II.

A crowned king without land, income or any real power of his own, he still had to govern while his father was in foreign lands and still had to maintain his own retinue and wife, whose dower lands were held by Henry II.  The Young King grew disheartened and impatient and, with nothing to give his mesnie, some began to encourage him to take action against his father. Whether the Marshal was amongst these, we don't know. However, from later records we know he was not beyond nagging, wheedling and begging his lord for reward: in a letter from Henry II to William discovered in 1996, Henry wrote that 'you have frequently complained to me that I have bestowed on you only a small fee'.

The Young King grew disheartened and impatient and, with nothing to give his mesnie, some began to encourage him to take action against his father. Whether the Marshal was amongst these, we don't know. However, from later records we know he was not beyond nagging, wheedling and begging his lord for reward: in a letter from Henry II to William discovered in 1996, Henry wrote that 'you have frequently complained to me that I have bestowed on you only a small fee'.

When the break with his father eventually came in 1173 Marshal supported the 18 year-old Young King, as did Eleanor, Young Henry's two brothers Richard and Geoffrey, and Louis VII, the Capetian king of France.  An invasion of Normandy was mounted but failed, as did a number of other invasions throughout the year. The civil war finished with a victory for Henry II, and a peace treaty was signed on 30 September 1174. Most traitors against Henry II were forgiven, including Marshal, but Eleanor spent over 10 years in captivity as a result. Whether this was because Henry felt especially betrayed by his wife, or whether it was because he thought her the cause of the revolt, is unknown.

An invasion of Normandy was mounted but failed, as did a number of other invasions throughout the year. The civil war finished with a victory for Henry II, and a peace treaty was signed on 30 September 1174. Most traitors against Henry II were forgiven, including Marshal, but Eleanor spent over 10 years in captivity as a result. Whether this was because Henry felt especially betrayed by his wife, or whether it was because he thought her the cause of the revolt, is unknown.

With nothing now to do, William and the Young King spent their days under the close scrutiny of Henry II, until restlessness got the better of them. Henry requested from his father the chance to visit the Continent, but was allowed only so far as Aquitaine to help his brother calm the lands there. While in France, one of Young Henry's mesnie was caught sending secret notes to Henry II and it was at this point in the summer of 1176, that Young Henry grew tired of the political game, and he and William devoted themselves to the tournament circuit.

The Marshal had an imposing figure, with strength, speed and agility. Tournaments, then, were ideally suited to him. Unlike the tournaments of popular imagination, portrayed in films and TV shows, those of the twelfth century focused less on the joust  and more on a mêlée, where teams of knights would fight over a large area of ground. The aim was to capture the opponents to ransom them, which could provide a good income for those, like Marshal, who were skilled.

and more on a mêlée, where teams of knights would fight over a large area of ground. The aim was to capture the opponents to ransom them, which could provide a good income for those, like Marshal, who were skilled.

Over the five years William spent on the circuit, he captured at least five hundred knights, winning himself considerable fame and fortune. Although banned in England at this time and disapproved of by the church, the tournament was popular on the Continent, being seen as a suitable occupation for bored warriors and younger sons and as a way to train for war. It was here that William, and every knight participating, honed battle skills, fitness and strategy. One of William's famous, and difficult, moves involved grabbing an opponent's horse by the reigns before leading them off to claim the prize, which is a trick he also used in battle. Another strategy employed by William was to hold the team back until the end of the day, hovering on the sidelines saying they just intended to watch. Once the other teams were tired, they would enter the fray, often winning glory as a result.  To a modern audience this seems like cheating, but the medieval mind saw it differently. Using cunning in a tournament, just as in battle, was something to be admired: reserves in battle were held back until the opponent's soldiers were tired, and so they were in the tournament. This is not to say there wasn't a code of honour. Once captured, a knight was honour-bound to pay his ransom, knights would respect and honour their lords, and their lords would reward them for it. Personal glory could be sought, but it was frowned upon to seek such glory to the detriment of the team. Those who performed well were honoured for it. After a tournament at Pleurs, Marshal was named the day's worthiest knight, but he couldn't be found to be presented with the ceremonial spear. He was eventually discovered on his knees in a blacksmith's, having his helmet beaten back into shape so he could lift it off his head.

To a modern audience this seems like cheating, but the medieval mind saw it differently. Using cunning in a tournament, just as in battle, was something to be admired: reserves in battle were held back until the opponent's soldiers were tired, and so they were in the tournament. This is not to say there wasn't a code of honour. Once captured, a knight was honour-bound to pay his ransom, knights would respect and honour their lords, and their lords would reward them for it. Personal glory could be sought, but it was frowned upon to seek such glory to the detriment of the team. Those who performed well were honoured for it. After a tournament at Pleurs, Marshal was named the day's worthiest knight, but he couldn't be found to be presented with the ceremonial spear. He was eventually discovered on his knees in a blacksmith's, having his helmet beaten back into shape so he could lift it off his head.

It was Marshal's feats of knightly prowess that led many to describe William as 'a man with a claim as good as any to be regarded as the first English celebrity'.  With such success and celebrity, William was allowed to become a 'knight banneret' – still in service to his lord, but with a retinue, colours and banners of his own. The arms he chose were a red lion against a halved green and gold background, echoing the lions of the Norman banner. These arms were to stay with him for the rest of his career.

With such success and celebrity, William was allowed to become a 'knight banneret' – still in service to his lord, but with a retinue, colours and banners of his own. The arms he chose were a red lion against a halved green and gold background, echoing the lions of the Norman banner. These arms were to stay with him for the rest of his career.

With Young Henry's tournament successes, he was drawn back into Angevin politics as the representative of the dynasty at the coronation of Philip II of France in 1179. But with this reintroduction to high politics came the same vexations of a king without land. His brothers were now happily settled on their own land,  and would never consent to be ruled by him as his vassals. In 1182, Young Henry made a formal request for the lands of Normandy, which was refused, and was compensated by an allowance of 100 Angevin pounds per day (with a further 10 for his wife). To force the issue further, Young Henry mooted the intention to go on crusade and looked to take the lands of Aquitaine directly from his brother, who was accused of cruelty towards its inhabitants.

and would never consent to be ruled by him as his vassals. In 1182, Young Henry made a formal request for the lands of Normandy, which was refused, and was compensated by an allowance of 100 Angevin pounds per day (with a further 10 for his wife). To force the issue further, Young Henry mooted the intention to go on crusade and looked to take the lands of Aquitaine directly from his brother, who was accused of cruelty towards its inhabitants.

It was in this scheming that rumours surrounding Marshal's disloyalty towards the Young King began to surface.  He was accused of having an affair with the Young King's wife, Marguerite, as well as taking honour away from the Young King at tournaments. It is likely that the accusation of adultery was a complete lie: there was nothing in either's behaviour, before or after, to suggest anything of the sort; and no direct or decisive action was taken against either accused party.

He was accused of having an affair with the Young King's wife, Marguerite, as well as taking honour away from the Young King at tournaments. It is likely that the accusation of adultery was a complete lie: there was nothing in either's behaviour, before or after, to suggest anything of the sort; and no direct or decisive action was taken against either accused party.  The other accusation, of acting dishonourably towards the Young King probably held more weight. To many, William may have appeared 'a social upstart – a mere knight, trying to step out beyond Young Henry's shadow.'

The other accusation, of acting dishonourably towards the Young King probably held more weight. To many, William may have appeared 'a social upstart – a mere knight, trying to step out beyond Young Henry's shadow.'  He had employed his own herald, Henry 'the Northerner', for tournaments and adapted Young Henry's own Norman battle-cry of 'God aid us' to 'God aid the Marshal'. This only seems like a small slight, but in raising himself above his station, Marshal was dishonouring both the Young King and himself.

He had employed his own herald, Henry 'the Northerner', for tournaments and adapted Young Henry's own Norman battle-cry of 'God aid us' to 'God aid the Marshal'. This only seems like a small slight, but in raising himself above his station, Marshal was dishonouring both the Young King and himself.

Although Henry didn't directly punish Marshal, he began withdrawing his favour and ignoring Marshal, and Henry's 'hatred for the Marshal was violent and bitter'.  Withdrawal of favour under the feudal system would have been obvious to everyone within the circle and immediately reduced Marshal's rank. Marshal withdrew from the king and avoided him wherever possible. They undertook one last tournament together late in 1182, where their quarrel was obvious to see. Marshal tried one last time to prove his innocence at the 1182 Christmas Angevin gathering, approaching Young Henry directly and offering trial by combat,

Withdrawal of favour under the feudal system would have been obvious to everyone within the circle and immediately reduced Marshal's rank. Marshal withdrew from the king and avoided him wherever possible. They undertook one last tournament together late in 1182, where their quarrel was obvious to see. Marshal tried one last time to prove his innocence at the 1182 Christmas Angevin gathering, approaching Young Henry directly and offering trial by combat,  but was refused. Letters of safe conduct to the Angevin border were granted by Henry II, and Marshal went into exile.

but was refused. Letters of safe conduct to the Angevin border were granted by Henry II, and Marshal went into exile.

The exile was not to last long: Young Henry pushed ahead with his plans to wage war on his brother Richard, and soon found he had need of Marshal.  In the spring of 1183, a rider was sent to find William, who was possibly returning from a pilgrimage to Cologne. The messenger reportedly told William that the plot against him had been found out, principally by the defection of one of his chief accusers to the Richard's side. Whatever the reason – expediency or a realization of the truth – William returned to the service of his lord in May 1183.

In the spring of 1183, a rider was sent to find William, who was possibly returning from a pilgrimage to Cologne. The messenger reportedly told William that the plot against him had been found out, principally by the defection of one of his chief accusers to the Richard's side. Whatever the reason – expediency or a realization of the truth – William returned to the service of his lord in May 1183.

But in late May, Young Henry contracted a fever, which gradually worsened. Said to be suffering from a flux of the bowels – dysentery – he died on 11 June 1183. One of his last wishes was for William to take the cross and fulfil Henry's obligations to go on crusade.

William spent two years in the Holy Land, where he came into contact with both the Hospitallers and the Templars. Very little is known about his time there. It was a few years of relative peace within the area and William would have participated in no pitched battles. We do know, however, that he met and was on good terms with Guy de Lusignan, one of the murderers of his former lord Salisbury and one of his captors. We also know his time there encouraged him to think about his religion and spirituality. In secret he bought pieces of silken cloth for his funeral shroud and made an internal vow to join the Knights Templar before his death.

King's man

William returned to the Angevin Empire in late 1185 or early 1186 and, presenting himself to Henry II, was given a position in the royal household, along with land and titles. The game changed when Marshal joined the court proper, where manners and a calm exterior were worth more than a hot-headed temper and quick action. Trained as a warrior and used to the tournament circuit, it is surprising that Marshal did so well in such situations, but from 1186 onwards, Henry II used Marshal as a leading household knight, who advised the King on military strategy and planning, although not yet on other aspects of government. In 1186, he was granted his first estate at Cartmel in Lancashire, provided from the king's own lands, which gave William an income of £32 per annum. He was given the wardship of Heloise of Lancaster, heiress of Kendal, one of the major lordships in northern England. This brought William considerable opportunities for advancing himself, giving him use of her estates until she married and providing him with a bargaining chip.  He was also given wardship over the 15-year-old John of Earley, the orphaned son of a West Country knight, whom William provided with a military education. Earley became his squire, and the two remained close friends throughout their lives. The increase in status and wealth provided by the estate and wardships allowed William to grow his own mesnie, with Earley and two other knights from Wiltshire, Geoffrey FitzRobert and William Waleran.

He was also given wardship over the 15-year-old John of Earley, the orphaned son of a West Country knight, whom William provided with a military education. Earley became his squire, and the two remained close friends throughout their lives. The increase in status and wealth provided by the estate and wardships allowed William to grow his own mesnie, with Earley and two other knights from Wiltshire, Geoffrey FitzRobert and William Waleran.

In late 1188, Henry II and his heir, Richard, fell out, plunging the Angevin Empire into another civil war.  Henry had weakened, both physically and in his ability to rule, since his last confrontation with a son, and a steady stream of lords left Henry's side to join Richard's cause. William, however, stayed loyal. With the king's retinue shrinking, William's importance grew and he was increasingly sent as an envoy to Richard and the Capetian king Philip II. As a reward for his loyalty he was given the wardship of the beautiful teenage heiress, Isabel of Clare, daughter of the late earl Richard Strongbow of Striguil, with land in the Welsh Marches, Wales, Normandy and Ireland. Her marriage would bring her husband all of these lands.

Henry had weakened, both physically and in his ability to rule, since his last confrontation with a son, and a steady stream of lords left Henry's side to join Richard's cause. William, however, stayed loyal. With the king's retinue shrinking, William's importance grew and he was increasingly sent as an envoy to Richard and the Capetian king Philip II. As a reward for his loyalty he was given the wardship of the beautiful teenage heiress, Isabel of Clare, daughter of the late earl Richard Strongbow of Striguil, with land in the Welsh Marches, Wales, Normandy and Ireland. Her marriage would bring her husband all of these lands.

When a peace conference between Richard and Henry in June 1189 ended in failure, the former took the opportunity to launch an offensive against Henry II (and against custom) immediately afterwards. Henry II and William were caught by surprise at Le Mans and beat a hasty retreat from the city, pursued by Richard himself. In order to protect the king, William wheeled his horse around to fight Richard in single combat. Neither was armoured, and the confrontation could have proved deadly, but just as William was about to strike with his lance, Richard shouted, 'God's legs, Marshal! Don't kill me.' William, exclaiming 'Let the Devil kill you!',  lowered his lance at the last moment, killing Richard's horse and driving Richard to the floor. Richard's pursuit of his father was over, but his life was not. Nor was his war: Richard wasn't taken prisoner, and he went on to capture the critically important city of Tours, where the Angevin treasury was kept.

lowered his lance at the last moment, killing Richard's horse and driving Richard to the floor. Richard's pursuit of his father was over, but his life was not. Nor was his war: Richard wasn't taken prisoner, and he went on to capture the critically important city of Tours, where the Angevin treasury was kept.

Despite the fact that the Old King's cause was completely lost and almost every knight had abandoned him before the end, William remained by the now-dying king's side  and tended to him during the ride to, and the wait before, the peace negotiations at Tours on 4 July 1189. Henry had little choice but to agree to the terms, including confirming Richard as his heir and promising Philip a tribute of 20,000 silver marks. All he requested in return was a list of those knights who had abandoned him.

and tended to him during the ride to, and the wait before, the peace negotiations at Tours on 4 July 1189. Henry had little choice but to agree to the terms, including confirming Richard as his heir and promising Philip a tribute of 20,000 silver marks. All he requested in return was a list of those knights who had abandoned him.  He made one last barb at Richard: in giving the ritual kiss of peace, Henry said 'God grant that I may not die until I have had my revenge on you.'

He made one last barb at Richard: in giving the ritual kiss of peace, Henry said 'God grant that I may not die until I have had my revenge on you.'

Henry didn't live long enough to exact his revenge, and died just two days later, on 6 July 1189.  Henry's body was moved to the nearby abbey at Fontevraud, where Marshal stood vigil. When Richard came, he spoke to Marshal in private and, whether impressed by Marshal's loyalty or because he needed military councillors of William's standing, took him into his own household, pledging to honour Marshal's guardianship of Isabel of Clare. Richard dealt in a similar fashion with other supporters of Henry II who had remained true to the end. Those who had abandoned him within the last few months were not so well treated, although nothing was done about John's defection.

Henry's body was moved to the nearby abbey at Fontevraud, where Marshal stood vigil. When Richard came, he spoke to Marshal in private and, whether impressed by Marshal's loyalty or because he needed military councillors of William's standing, took him into his own household, pledging to honour Marshal's guardianship of Isabel of Clare. Richard dealt in a similar fashion with other supporters of Henry II who had remained true to the end. Those who had abandoned him within the last few months were not so well treated, although nothing was done about John's defection.

William married Isabel in late July 1189 and then went on a brief 'honeymoon', lodging at the manor of Stoke d'Aubernon.  Although purely a political match, the couple developed a strong relationship, and produced ten children, including five sons. There is no evidence, even in a time when male infidelity was common, that Marshal ever took a mistress, and it seems to have been a successful marriage. The marriage gave Marshal several large estates across the Marches and he moved into Striguil (now Chepstow) Castle. With additional land came additional power, and his mesnie increased to between 15 and 20 knights. As well as knights, he employed chaplains

Although purely a political match, the couple developed a strong relationship, and produced ten children, including five sons. There is no evidence, even in a time when male infidelity was common, that Marshal ever took a mistress, and it seems to have been a successful marriage. The marriage gave Marshal several large estates across the Marches and he moved into Striguil (now Chepstow) Castle. With additional land came additional power, and his mesnie increased to between 15 and 20 knights. As well as knights, he employed chaplains  to take care of religious aspects and clerks to oversee day-to-day administration.

to take care of religious aspects and clerks to oversee day-to-day administration.  The additional land also brought in additional wealth and over the years he managed to amass a considerable fortune, particularly through the thriving wool trade.

The additional land also brought in additional wealth and over the years he managed to amass a considerable fortune, particularly through the thriving wool trade.

Divided loyalties

In April 1190, Richard departed Dartmouth for the Third Crusade, leaving his brother John and a small group of advisers, including Marshal, behind. It wasn't long before John started scheming against his brother, giving himself effective regency over the country and being considered as Richard's heir. We don't entirely know Marshal's role in this, or how much he supported John, his neighbour in England, his overlord and to whom he swore fealty for his Irish lands in Leinster and, potentially (given the dangers inherent in crusading) his next king. Richard later asked Marshal to swear fealty to him for Leinster, but William refused, stating that he had already sworn fealty to John and that to swear to someone else would be treacherous. This to the letter of the law was true, but it probably also reflects William's awareness that John would be his future patron. There is nothing that Marshal did that was disloyal to Richard, but where Richard himself wasn't actually threatened, he kept a steady neutrality. As Ashbridge says, this could be 'prudent agility, but the trace scent of self-service seems undeniable'. This approach certainly led some to question William's reputation of steadfast loyalty: the courtier William Longchamp accused Marshal of 'planting vines', or laying the groundwork for the next monarch.

This approach certainly led some to question William's reputation of steadfast loyalty: the courtier William Longchamp accused Marshal of 'planting vines', or laying the groundwork for the next monarch.

Richard returned safely to Europe from Jerusalem late in 1192, but was captured – despite the protection afforded to crusaders – by Duke Leopold V of Austria (whom Richard had offended) and imprisoned in Vienna. News reached England and France in January 1193. John immediately started scheming with Philip II of France, spreading rumours that Richard was dead and seizing Nottingham, Windsor, and Wallingford castles. Proof soon arrived that Richard was still alive and Marshal and other loyalists set about recapturing the castles taken by John and fortifying the coastal defences against a French invasion. John made desperate overtures to Philip for protection, giving away much of Normandy – including Marshal's estate at Longueville – in the process.

Richard was released after 14 months in captivity in February 1194, for the sum of 100,000 marks and hostages to guarantee a further 50,000. He reached England in March, just as William was grieving for the death of his elder brother, John.  William inherited John's official title of royal master-marshal, and hurriedly arranged John's funeral before rushing off to meet Richard at Huntingdon.

William inherited John's official title of royal master-marshal, and hurriedly arranged John's funeral before rushing off to meet Richard at Huntingdon.  Richard and his retinue, including Marshal, recaptured the remaining rebel strongholds in England, finishing at Nottingham.

Richard and his retinue, including Marshal, recaptured the remaining rebel strongholds in England, finishing at Nottingham.  After a brief crowning ceremony in April 1194, Richard, William and a number of other warriors set sail to restore the lands in France.

After a brief crowning ceremony in April 1194, Richard, William and a number of other warriors set sail to restore the lands in France.  The defeated John came trembling to Richard to ask for forgiveness, which was instantly given. But during the campaign to regain his lands in 1199 Richard took a crossbow bolt in his shoulder. Although the bolt was removed, the wound turned gangrenous and on 6 April 1199, Richard died.

The defeated John came trembling to Richard to ask for forgiveness, which was instantly given. But during the campaign to regain his lands in 1199 Richard took a crossbow bolt in his shoulder. Although the bolt was removed, the wound turned gangrenous and on 6 April 1199, Richard died.

Marshal and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter, were at Rouen when news of Richard's death, but not news of the succession, reached them. With two claimants to the throne, they now had to decide who to support: Richard's brother John, or the 12-year-old Arthur of Brittany, the son of John's late elder brother.  Marshal favoured John, arguing that Arthur had bad advisers, that he was unapproachable and overbearing. Walter eventually agreed, but told Marshal 'You will never come to regret anything you did as much as what you are doing now'.

Marshal favoured John, arguing that Arthur had bad advisers, that he was unapproachable and overbearing. Walter eventually agreed, but told Marshal 'You will never come to regret anything you did as much as what you are doing now'.  There was obviously a reasonable amount of self interest in the decision: William already knew John, had turned a blind eye to much of his behaviour during Richard's absence, and was already an established figure at his court; Arthur was an unknown quantity, with different advisers, and his accession would effectively mean a demotion for William. But as Ashbridge argues, for Marshal, during a time of war with France, 'the choice between an unproven boy and a fully grown man, with experience of war, was no choice at all.'

There was obviously a reasonable amount of self interest in the decision: William already knew John, had turned a blind eye to much of his behaviour during Richard's absence, and was already an established figure at his court; Arthur was an unknown quantity, with different advisers, and his accession would effectively mean a demotion for William. But as Ashbridge argues, for Marshal, during a time of war with France, 'the choice between an unproven boy and a fully grown man, with experience of war, was no choice at all.'  Marshal was duly rewarded for his efforts: in May 1199 he was appointed earl of Pembroke, the highest rank available to those outside the royal family during the twelfth century.

Marshal was duly rewarded for his efforts: in May 1199 he was appointed earl of Pembroke, the highest rank available to those outside the royal family during the twelfth century.

Trouble with Bad King John

John's reign was not successful. With a possible other successor to Richard still alive, there were immediate questions over his right to rule, of which Philip II made the most. During 1202 and 1203, John, with Marshal at his side, made an attempt to keep the French lands intact. There was a brief glimmer of hope after John scored an astounding victory at the besieged castle at Mirebeau. The French laying siege to the castle were quickly defeated in a surprise attack, with 252 knights and Arthur of Brittany taken captive. However, instead of behaving correctly, the knights were starved to death and Arthur likely murdered, either by John himself or by one of his close associates. Any little support John had in France fell away and in December 1203, the royal party, including Marshal, returned to England: Normandy was lost. This, of course, meant that many of the Anglo-Norman nobility who held lands on both sides of the Channel had to make a choice: they could swear fealty to one king or the other, but not to both. Whatever choice they made, they had to lose some of their lands. Marshal tried desperately to avoid this by making an agreement with John that he would pay homage to Philip but not as his vassal. John, the History states, agreed to these terms and issued a letter allowing it. However, when it came to taking the oath, Philip exacted harder terms: he wanted to be Marshal's liege-lord on the French side of the Channel, and, backed into a corner, Marshal agreed. John, even without his whimsical temper, would not have been impressed. He was livid that Marshal had sworn such an oath and as the History observes, 'the Marshal was on bad terms with the King for a long time.'

The situation came to a head when John called on Marshal in June 1205, in front of a large group of barons, to sail to France to help him recover lands over there. Marshal refused, saying his oath meant that in France he would have to fight for Philip. A quarrel ensued, with Marshal's loyalty to the crown being questioned. Marshal offered trial by single combat to prove his loyalty, which no-one was willing to take up. However, the knights bearing witness to the quarrel were moved to question his motives and his fidelity. The argument ended in stalemate, but thereafter royal favour was slowly withdrawn from Marshal until, by 1206, there was no mention of Marshal in royal documents: he was out in the cold. Furthermore, he had to surrender his eldest son, Young William Marshal, to the king as a ward, although there can be little doubt he was a hostage for William's good behaviour.

Without the ability to pursue land, power and favour in England and France, Marshal looked to his estates in the west. In 1207, he went to Leinster in Ireland, clutching the royal licence allowing him to travel, but ignoring the inconsistent John's demand that he stay in England. We don't know much about William's behaviour in Ireland, although it appears he was firm but fair with his vassals. He was less fair to the native population, and one argument over land led to him being condemned by the Irish church.

A letter of complaint from Marshal and other Irish barons about John's representative in Ireland gave John the pretext for summoning Marshal back to England. Although he feared a trap, Marshal had to respond to a direct summons or be declared a traitor. He made defensive preparations to secure the Leinster lands in his absence and to protect his pregnant wife, who was in too delicate a condition to attempt the crossing. Leaving the majority of his mesnie in Ireland,  William travelled with a small contingent to meet John at Woodstock. Once there, the trap started closing: the king granted William's men land and title enough to turn them away from William's service

William travelled with a small contingent to meet John at Woodstock. Once there, the trap started closing: the king granted William's men land and title enough to turn them away from William's service  Further summons were sent for the supporters remaining in Ireland, which would leave Leinster, and William's wife, undefended. Nothing was heard from them for weeks until, on 25 January 1208, John gave Marshal news that Kilkenny Castle had been besieged and his supporters killed.

Further summons were sent for the supporters remaining in Ireland, which would leave Leinster, and William's wife, undefended. Nothing was heard from them for weeks until, on 25 January 1208, John gave Marshal news that Kilkenny Castle had been besieged and his supporters killed.

John lied about the deaths of William's supporters. They had indeed opted not to respond to the summons, forfeiting their own lands, and to stay loyal to Marshal. This loyalty upheld the developing notions of chivalry within the landed classes, placing honour and obligation above self-interest. But it also showed the respect and admiration that William could inspire in his men. His supporters forged an alliance with the Lacys of Ulster and, with significant reinforcements, won the Leinster war. John's representative and the former members of William's mesnie who had gone back to Ireland in support of John were captured, and hostages were handed over. News reached John in either late February or early March and, although William also heard the news, William feigned ignorance at a meeting with the king on 5 March. A reconciliation was achieved: William kept his lands in Leinster, although he forfeited a few rights of appointment for bishops and similar. William also acknowledged his status as John's subject in Ireland. He returned to Ireland in April 1208 with the king's agreement, although it was around this time he was forced to hand over his second son, Richard, as another hostage. The turncoats were treated generally with leniency, but some ended up as social pariahs and others were forced to give their children as hostages.

William's troubles with King John didn't end there and John was soon back on the warpath, although this time William was caught in the crossfire rather than being the main target. The paranoid king requested a hostage from William's Marcher neighbour and friend William of Briouze, the man who had been party to the death of Arthur. But when the demand came, William's wife made the impolitic remark that she would never surrender her own son as hostage to a king who killed his own nephew. The family went on the run, and William sheltered them for a while on his Leinster estates. When John's representative came for them, Marshal claimed no prior knowledge of their arrest warrants and said they were therefore protected by the laws of hospitality. Unwilling to push the argument with John further, William arranged for the Briouzes to be escorted to the Lacys, to whom they were connected by marriage. William of Briouze escaped into exile in France, where he spread rumours of Arthur's untimely end, before dying in 1211. His wife and son were captured, thrown into prison and starved to death  and the Lacys had their lands confiscated. For the crime of sheltering them, Dunamase Castle was confiscated from William and a number of his retinue were placed in crown custody.

and the Lacys had their lands confiscated. For the crime of sheltering them, Dunamase Castle was confiscated from William and a number of his retinue were placed in crown custody.

John lurched from crisis to crisis, with revolts in Wales, possible plots of assassination, excommunication from the Catholic Church and increasing disapproval of his personality and reign. In addition to his way of disposing of enemies, which led to general disapprobation amongst the barons, he enforced harsh taxes on inheritance, marriage and scutage. As Roger of Wendover noted in Flores historiarum, John 'had almost as many enemies as barons'.

The situation was so dire that 'although William may have distrusted, disliked and perhaps even feared his monarch, it turned out – somewhat ironically – that he was still the closest thing to a friend that John had amongst the English nobility.'  By the summer of 1212, the situation reached a peak and Marshal, whether driven by self-interest, the protection of his hostage sons, a sense of chivalric duty, or loyalty to the Angevin crown, wrote a letter to John pledging his support, offering to come to England if required. John snatched upon the chance to remedy the relationship: although not requiring Marshal's presence in England, over the next few years he granted several other offices and estates to Marshal. Both his sons and his retinue were freed and advanced where possible. 'Marshal would prove to be one of John's most important allies and unflinching servants from this point onwards, even as almost all others fell away and the tide turned irrevocably against the King.'

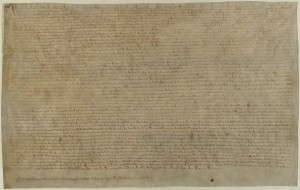

By the summer of 1212, the situation reached a peak and Marshal, whether driven by self-interest, the protection of his hostage sons, a sense of chivalric duty, or loyalty to the Angevin crown, wrote a letter to John pledging his support, offering to come to England if required. John snatched upon the chance to remedy the relationship: although not requiring Marshal's presence in England, over the next few years he granted several other offices and estates to Marshal. Both his sons and his retinue were freed and advanced where possible. 'Marshal would prove to be one of John's most important allies and unflinching servants from this point onwards, even as almost all others fell away and the tide turned irrevocably against the King.'  As John's ally, he became heavily involved in the negotiations between the king and the barons that led to Magna Carta. Some have even claimed he was Magna Carta's main architect,

As John's ally, he became heavily involved in the negotiations between the king and the barons that led to Magna Carta. Some have even claimed he was Magna Carta's main architect,  and William's name is the first of the king's advisers to appear on it.

and William's name is the first of the king's advisers to appear on it.

Regent of the realm

Despite the war that was the result of John's failure to uphold Magna Carta and the ensuing Capetian invasion of England, Marshal stuck by John until the very end. John died of dysentery on 19 October 1216, having supposedly gorged himself on too much cider and too many peaches. Before he died, John gave the care and well-being of his son and heir, the nine-year-old Henry, to Marshal. The loyal Marshal could do little else, then, but to risk his estates and ambitions by favouring Henry's claim to the throne, at a time when a considerable portion of England favoured Philip II for king. Some historians have put his decision to back Henry as self-serving; a gamble that, if it paid off, would provide him with even greater power and advancement. However in 1216 it was by no means certain whether Henry would become king, and greater advantage could have been found in the Capetian camp.

Henry III was crowned on 28 October 1216, after William had dubbed him as a knight.  The following day William took the role of regent

The following day William took the role of regent  and secular leader of the royalist cause. For his troubles, the Italian papal legate Guala of Bicchieri, gave William a full remission and pardon of his sins. But a crown did not secure a kingdom, and Marshal now had the task of convincing the rebels to support the new king. At first, neither the rebels nor the Capetians relented and Henry III was close to broke. To help solve the latter problem, Marshal sold a number of royal jewels to contribute to the defence of castles such as Dover and for mercenaries. As enticement to the rebels, the 1215 charter was reissued (with a few bits missing) and rebels wishing to rejoin the royalists were offered amnesty. While Louis, the son of Philip II, was campaigning in the country, this had little effect but over the winter a truce was called and a number of rebels returned to the royalists, including Young William Marshal, the Marshal's eldest son. Guala, with the authority of the Church, announced that supporting the royalists was tantamount to a crusade, offering all those who fought in Henry's name remission of their sins.

and secular leader of the royalist cause. For his troubles, the Italian papal legate Guala of Bicchieri, gave William a full remission and pardon of his sins. But a crown did not secure a kingdom, and Marshal now had the task of convincing the rebels to support the new king. At first, neither the rebels nor the Capetians relented and Henry III was close to broke. To help solve the latter problem, Marshal sold a number of royal jewels to contribute to the defence of castles such as Dover and for mercenaries. As enticement to the rebels, the 1215 charter was reissued (with a few bits missing) and rebels wishing to rejoin the royalists were offered amnesty. While Louis, the son of Philip II, was campaigning in the country, this had little effect but over the winter a truce was called and a number of rebels returned to the royalists, including Young William Marshal, the Marshal's eldest son. Guala, with the authority of the Church, announced that supporting the royalists was tantamount to a crusade, offering all those who fought in Henry's name remission of their sins.  Those who supported the Capetian cause faced excommunication.

Those who supported the Capetian cause faced excommunication.

Despite this, Henry was still in a precarious position and Marshal realized the only chance of success was a decisive victory. Though he was now 70, William saw his chance in a pitched battle outside the besieged royalist castle in Lincoln. On 20 May 1217, in a battle that has been described as 'one of the most decisive in English history',  Marshal marched his army to Lincoln, and waited outside the city walls. The Anglo-French army, refusing to take Marshal's bait, retreated into the city, believing themselves safe. By midday, their barricade was removed, and Marshal and his men charged through into the Anglo-French forces.

Marshal marched his army to Lincoln, and waited outside the city walls. The Anglo-French army, refusing to take Marshal's bait, retreated into the city, believing themselves safe. By midday, their barricade was removed, and Marshal and his men charged through into the Anglo-French forces.  Henry's forces poured into the city with such force that Marshal himself plunged three lances deep into the press, with the Bishop of Winchester continuously shouting William's old tournament cry of 'God aid the Marshal'. The French commander, Thomas of Perche, made a last stand outside Lincoln Cathedral, and according to the biographer, landed three heavy blows on William's helmet, before he was killed by a spear through his visor. Those Anglo-French forces who could, fled; those who couldn't were taken captive. 'The heart had been ripped from Louis' party in England.'

Henry's forces poured into the city with such force that Marshal himself plunged three lances deep into the press, with the Bishop of Winchester continuously shouting William's old tournament cry of 'God aid the Marshal'. The French commander, Thomas of Perche, made a last stand outside Lincoln Cathedral, and according to the biographer, landed three heavy blows on William's helmet, before he was killed by a spear through his visor. Those Anglo-French forces who could, fled; those who couldn't were taken captive. 'The heart had been ripped from Louis' party in England.'

Despite best attempts, no peace was agreed until a final naval battle, this time not led by William, occurred at Sandwich on 24 August 1217. The French were once again beaten and Henry's crown was secured: Louis entered into peace talks, and agreed to recognize Henry as king, acknowledged his right to the Channel Islands, promised to help Henry recover his lost lands in France and agreed never again to help English rebels. In return, Marshal paid Louis £7,000.

This treaty has led many to question Marshal's wisdom, and even courage, both at the time and since. Many have wondered why Marshal didn't press the advantage and completely eliminate the French threat, or take the war to France. After all, the Capetians were on the back foot, and it could have been easy to retake the Angevin territories. However, peace in England was still not assured, and Henry III was still broke. Perhaps William shouldn't have trusted Louis's word,  but it could be said that he was working on a system of honour not upheld by his French adversary. It could also be suggested that age was, perhaps, getting the best of him.

but it could be said that he was working on a system of honour not upheld by his French adversary. It could also be suggested that age was, perhaps, getting the best of him.

William remained regent until early 1219. He did what he could to restore the legal and financial system of England, as well as its borders.  The Charter was reissued in 1217 bearing Marshal's seal, and some semblance of financial control returned. In general, Marshal is considered to have done well: 'There was no scent of overbearing tyranny, and only the barest hint of partisan self-service, to Earl William's rule.'

The Charter was reissued in 1217 bearing Marshal's seal, and some semblance of financial control returned. In general, Marshal is considered to have done well: 'There was no scent of overbearing tyranny, and only the barest hint of partisan self-service, to Earl William's rule.'  He took custody of Gloucester Castle and the right of free passage of ships to the port of New Ross in Leinster. He also made sure those loyal to him were provided for: Young William Marshal was given Marlborough Castle, John Marshal, the illegitimate son of his late elder brother, oversight of the royal forests, and other followers, including his former squire Earley, grants of land.

He took custody of Gloucester Castle and the right of free passage of ships to the port of New Ross in Leinster. He also made sure those loyal to him were provided for: Young William Marshal was given Marlborough Castle, John Marshal, the illegitimate son of his late elder brother, oversight of the royal forests, and other followers, including his former squire Earley, grants of land.

Early in 1219 aged 72, after travelling from Marlborough to Westminster, Marshal fell ill, and by the middle of March 1219, he knew his end was approaching. On 20 March 1219, he decided to move from London to his manor at Caversham, although for a number of weeks he continued to manage affairs of state from his bed. Wracked with pain and with no appetite, on 8 April William initiated a two-day debate between the king and his counsellors about passing the regency to someone else and Henry was eventually given into the care of the papal legate Pandulf.

With the weight of state affairs lifted, Marshal was able to set his own personal affairs in order. He ensured provision for his wife while she remained alive, divided his estates between four of his sons (the fifth was due to make a career in the church), and provided income for his fifth daughter (the other four already being married). Early in May 1219, Marshal declared his intention to join the Templars, and the master of the Templars travelled to Caversham to perform the rite. Immediately beforehand, he called Isabel to his side to give her one final kiss.  She did so and they both wept.

She did so and they both wept.

At around midday on Tuesday 14 May, Marshal died. His body was transported to Reading Abbey for Mass, and then taken in procession to London on 18 May, escorted by a large crowd of barons. A further Mass was performed before he was laid to rest in Temple Church. In his oration, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, was said to have described Marshal as 'the greatest knight to be found in all the world'.

Marshal's early career on the tournament circuit, together with his enthusiasm for fighting, have led some to suggest he was all brawn and no brains. Duby and Painter both thought him somewhat simple, with Duby stating he was 'blessed with a brain too small to impede the natural vigour of a big, powerful and tireless physique'.  But this doesn't fit with his career at court, his ability to steer through the pitfalls of John's reign and to rule a broken and fragile kingdom as regent during the last years of his life. He was politically deft enough to realize the potential of a reissued Magna Carta as a way of bringing the barons back to the royalist cause, and to 'stand as the foundation of a new monarchy.'

But this doesn't fit with his career at court, his ability to steer through the pitfalls of John's reign and to rule a broken and fragile kingdom as regent during the last years of his life. He was politically deft enough to realize the potential of a reissued Magna Carta as a way of bringing the barons back to the royalist cause, and to 'stand as the foundation of a new monarchy.'  Perhaps, without Marshal's involvement, Magna Carta would never have become the document of legend that it is today. As Crouch says, 'He was no lucky bonehead. He was an astute, alert and cool-headed soldier and courtier…and no man's fool.'

Perhaps, without Marshal's involvement, Magna Carta would never have become the document of legend that it is today. As Crouch says, 'He was no lucky bonehead. He was an astute, alert and cool-headed soldier and courtier…and no man's fool.'

Things to think about

- Why did John Marshal gamble with his son’s life, and what can we infer about their relationship from this? Was this true of all father-son relationships in the mid-twelfth century?

- What does William’s story tell us about social mobility in the medieval period?

- What can we learn about twelfth century society from studying Marshal? What does it teach us about notions of chivalry, warfare and politics?

- Was Marshal really a chivalrous knight, or was he moved more by self-interest?

- Was William Marshal really ‘the greatest knight’?

- How does studying Marshal’s life give us a fresh perspective on the Angevin kings?

- What can we learn about the role of women from Marshal’s story?

Things to do

- Although it has been expanded and modernized in the time since William Marshal lived there, Chepstow Castle still stands relatively intact. It often hosts Marshal-related events and it is still possible to see the 800 year-old castle doors. Find out more information about the castle here.

- Another castle associated with Marshal, although most of it is of a later design, is Pembroke Castle. Click here to find out more information about visiting.

- It is possible to visit Temple Church in London, where Marshal’s tomb effigy can still be seen. Find out more information about it here.

Further reading

One of the best books to read for more information on William Marshal is Thomas Ashbridge's The Greatest Knight: The Remarkable Life of William Marshal, the Power behind Five English Thrones, which is easy to read and full of information not just about Marshal but about the history of the twelfth century. The translated version of History of William Marshal by Holden, Crouch and Gregory is expensive and difficult to find, but for those really interested in the subject, it is easily the best source. Visit the Anglo-Norman Text Society website for more information.