Key facts about Magna Carta

- Magna Carta was sealed at Runnymede by King John on 15 June 1215

- King John was forced to agree to it by rebellious barons

- It is said to be the basis for civil and human rights

- It focuses on the rights of the barons, rather than the common people

- It was annulled after 10 weeks

People you need to know

- Henry I - a Norman king who ruled from 1100 until 1135.

- Henry III - son of King John and king from 1216 until 1272.

- Pope Innocent III - one of the most powerful and influential popes, he reigned from 1198 until 1216.

- King John - king from 1199 until 1216, he is generally considered a bad king.

Magna Carta (meaning 'Great Charter') is legendary as the foundation of modern human and civil rights, and of our current systems of government and law. Many look to its legend to give themselves authority legally or politically, and the last 33 British monarchs have sworn to uphold it. It is also said to have inspired the likes of the European Convention on Human Rights and the American Constitution. It has been discussed to such lengths that one judge and historian, Jonathan Sumption, said of it ‘It is impossible to say anything new about Magna Carta, unless you say something mad. In fact, even if you say something mad, the likelihood is that it will have been said before, probably quite recently.’  In a recent court case, one Plymouth resident argued against an injunction by the council based on a clause in the Great Charter, while the former prime minister David Cameron referred to it as the document that paved the way for democracy, equality and the rule of law, the ‘foundation of all our laws and liberties’. It would not be too far a stretch to consider Magna Carta as one of the founding myths of England, but is there any substance to it?

In a recent court case, one Plymouth resident argued against an injunction by the council based on a clause in the Great Charter, while the former prime minister David Cameron referred to it as the document that paved the way for democracy, equality and the rule of law, the ‘foundation of all our laws and liberties’. It would not be too far a stretch to consider Magna Carta as one of the founding myths of England, but is there any substance to it?

Magna Carta – or the ‘Article of the Barons’ as it was first known – was a result of the (mainly) northern barons' defiance against King John’s demands for money, his losses in war, and his absolute failure to abide by any code of chivalry and honour. In the years before 1215, John was unsuccessfully fighting to defend his French territories and paying for his wars with the possessions and estates of the barons, killing those who refused, and leaving women and children to starve, until those barons reached breaking point. They waged war on John, capturing London, before forcing him to submit to their demands in a field at Runnymede, which may - or may not - have been a place traditionally used for such negotiations.  These demands became the 63 clauses of Magna Carta, and tackled all manner of complaints, from fish weirs in the Thames to the rights of free people to be given a fair trial. The most important clauses, 39 and 40, state that:

These demands became the 63 clauses of Magna Carta, and tackled all manner of complaints, from fish weirs in the Thames to the rights of free people to be given a fair trial. The most important clauses, 39 and 40, state that:

No free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseized, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the legal judgement of his peers or by the law of the land

and

To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay, right or justice

Other clauses state that ‘There shall be one measure of wine in the whole of our realm, and one measure of ale, and one measure of corn’. They enshrined the freedom of the Church ‘in perpetuity’ and guaranteed the rights of the City of London. It is some of these points which have given Magna Carta the status it has today: clause 39 can still be found in the statute book.

It is generally believed Magna Carta established a new constitutional framework, which for the first time placed the king under the law of the land. However, the notion that the monarch was answerable to the law was not a new one. Before Magna Carta, it was commonly acknowledged that the king was subject to the law, whether the law be from the Christian god or from tradition and custom. The pre-eminent political theorist in the twelfth century, John of Salisbury, showed that the difference between a king and a tyrant was willingness to abide by the law. Upon his accession to the throne in 1100, Henry I made an oath, which went down in history as his Charter of Liberties, that he would abide by the law and every monarch thereafter drew up similar documents, modelled on his.  The Charter of Liberties was even referred to during the negotiations for Magna Carta. The Article of the Barons was therefore more concerned with defining laws than with establishing whether or not the king should abide by them.

The Charter of Liberties was even referred to during the negotiations for Magna Carta. The Article of the Barons was therefore more concerned with defining laws than with establishing whether or not the king should abide by them.

The laws proposed in the Great Charter were primarily concerned with feudal would protect everyone, the peasants would pay for this protection by working the land, and the clergy would pray for everyone. In the secular world, the monarch was at the top of the pyramid, with each layer of nobility…, sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character. would protect everyone, the peasants would pay for this protection by working the land, and the clergy would pray for everyone. In the secular world, the monarch was at the top of the pyramid, with each layer of nobility… rights and obligations rather than with the common man. Sumption says ‘It sought to enforce on the King conventions which were profoundly traditional, and obligations which he and his predecessors had acknowledged for more than a century. There are no high-flown declarations of principle.’  Those clauses generally considered to have provided the basis for modern human rights, such as the right to a trial by jury and habeas corpus (the right not to be imprisoned unlawfully), were not relevant to criminal settings (where trials were usually done by ordeal or battle) but were attempts by the barons to limit the monarchy from swiping their estates. Arrest on the monarch’s whim (and therefore against modern notions of habeas corpus) was still practised well into the seventeenth century.

Those clauses generally considered to have provided the basis for modern human rights, such as the right to a trial by jury and habeas corpus (the right not to be imprisoned unlawfully), were not relevant to criminal settings (where trials were usually done by ordeal or battle) but were attempts by the barons to limit the monarchy from swiping their estates. Arrest on the monarch’s whim (and therefore against modern notions of habeas corpus) was still practised well into the seventeenth century.

What was far more relevant to the vast majority of the king’s subjects was the Charter of the Forest, which was drawn up in 1217, and offered some economic protection to the peasantry as well as rolling back some of the common land rights lost to them following the Norman invasion. It was in this that the rights of the majority began to emerge, rather than in its earlier cousin, and it was only when they were joined in 1297 that Magna Carta began to be a charter for all. Furthermore, the original Magna Carta, sealed in 1215, was very unsuccessful. Not only did it rely on the threat of violence to protect peace, in the so-called 'security clause' (clause 61), but John also had it annulled by Pope Innocent III just 10 weeks later. The Pope called it ‘not only shameful and base but illegal and unjust’ and forbade John to adhere to it on pain of excommunication. It was this reneging on the agreement at Runnymede that led to the First Baron’s War. It was only when John died in 1216 that the rebel barons were brought back on side by the promise that John’s nine-year old heir, Henry III, would adhere to Magna Carta, and it was reissued with several clauses missing.

It was this reissue, prompted by the far-sighted regent, William Marshal, and papal legate, Guala of Bicchieri, that led to Magna Carta's place in the history books. The original charter was a non-entity, considered defunct by both parties, yet the new charter breathed new life into English politics. As Thomas Ashbridge says, 'It was not a mere peace treaty, extracted under duress from an embattled monarch, but a freely given assurance of rights.' This, along with the papal approval that was so disastrously missing from the first document, immediately gave Magna Carta more longevity. And it was this longevity that allowed the 'momentously open-ended'

This, along with the papal approval that was so disastrously missing from the first document, immediately gave Magna Carta more longevity. And it was this longevity that allowed the 'momentously open-ended' rights of the first charter to become what they are today.

rights of the first charter to become what they are today.

Things to think about

- How important is Magna Carta to our own laws and methods of governance?

- How successful was Magna Carta in the thirteenth century?

- Has Magna Carta ever been important?

- Why has Magna Carta got such as positive reputation?

- What can we learn about King John from the Magna Carta story?

Things to do

- Runnymede is a field with a memorial put up by the American Bar Association in 1957, and is owned by the National Trust. There isn't much to see or do, but it can make a pleasant walk and has become something of a site of pilgrimage. Find out more about visiting here.

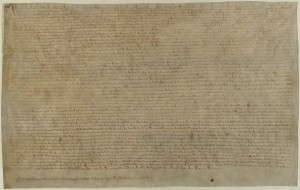

- There are four copies of the original Magna Carta, and it is possible to see most of them. They are on display in the Treasures of the British Library exhibition at the British Library (information for which is here), at Salisbury Cathedral (find out information here), and usually it's also at Lincoln Cathedral (information here).

- The British Library also has an excellent online Magna Carta resource. You can find it here.

Further reading

There are a huge number of books available on Magna Carta and topics linked with it: An easy and cheap introduction is Nicholas Vincent's Magna Carta: A Very Short Introduction (part of the OUP Very Short Introductions series). A further light-hearted and chatty introduction is Dan Jones' Magna Carta: The Making and Legacy of the Great Charter. For information about King John, Marc Morris' book King John: Treachery, Tyranny and the Road to Magna Carta is worth reading. For a wider social and political history of the age, try reading Danny Danziger's 1215: The Year of Magna Carta.