Guest article by Steven Port

Key facts about literature at the court of Richard II

- The reign of Richard II witnessed some significant changes

- One considerable change was in the development of literature, particularly of that written in the English language.

- Historians can't agree how much Richard II influenced the development of literature.

- It is difficult to say how much personal interest in, or enjoyment of, literature that Richard II had.

- Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower both had connections to the court, but they were not sponsored 'court poets'.

- The nature of the court allowed literature, and other arts, to flourish.

People you need to know

- Charles V - king of France between 1364 until his death in 1380. As well as a warrior, he was considered a cultured and moral king.

- Charles VI - king of France between 1380 and 1422, known first as 'the Beloved' and then as 'the Mad'. His daughter, Isabella, became Richard II's second wife.

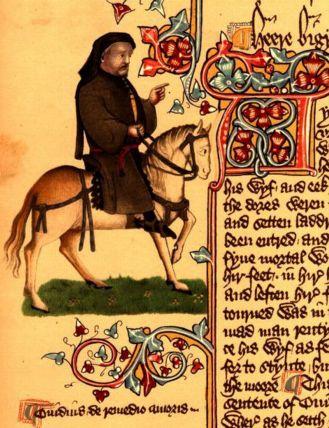

- Geoffrey Chaucer - often called the 'father of English literature', he was a poet, philosopher, and astronomer, as well as a civil servant.

- Edward III - warrior king of England, who ruled from 1327

d'etat by his mother, Isabella of France and her lover Roger Mortimer, against Edward II. They attempted to rule in his name but, in 1330, Edward III had Mortimer captured and executed. His mother was allowed to live out her life in peace, but away from the court. until his death in 1377.

d'etat by his mother, Isabella of France and her lover Roger Mortimer, against Edward II. They attempted to rule in his name but, in 1330, Edward III had Mortimer captured and executed. His mother was allowed to live out her life in peace, but away from the court. until his death in 1377. - Jean Froissart - French-speaking poet and historian from the Low Countries, who is perhaps best known for his tales of chivalry and the first part of the Hundred Years' War.

- John Gower - influential English poet, and friend of Chaucer.

- Richard II - king of England from 1377 until he was deposed by his cousin in 1399. By many he was considered a much weaker, effeminate king than his predecessor, Edward III.

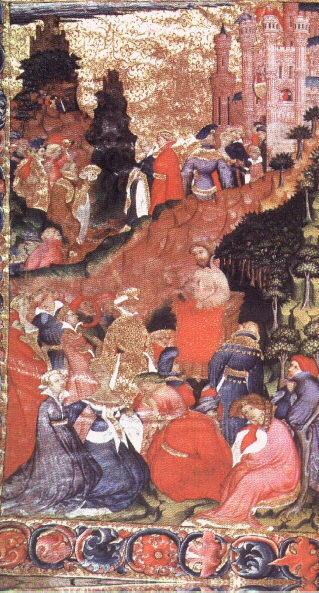

The last two decades of the fourteenth century stand out in English history, distinguished by cultural, social and political shifts that have echoed through the centuries. The battles over the relationship between monarchy and government were unlike any that had come before, and were to resurface in the seventeenth century with a similar but longer-lasting outcome. The Black Death and the economic changes that had begun in the mid-fourteenth century, and the opportunities for social mobility they allowed, began to alter dramatically views of what 'society' meant. Yet perhaps the most widely-accepted and lauded change in this period came with the development of literary culture. The works of poets such as Geoffrey Chaucer, which are still studied in schools today, and the subtlety and varied stylistic approaches they demonstrate, mark a defining moment in the development of English creative endeavour and a revolution in the history of English as an artistic language.

Academic debates

Traditional approaches to the study of this period have attributed much of the new wave of poetry to the openness and encouragement of Richard II’s court. Gervase Mathew paints a picture of a royal household revelling in a creative ambience, commissioning illuminated manuscripts, bold architectural projects, and boasting the 'greatest vernacular literature in Europe'. However, more recent analyses have cast doubt on this image, at times dismissing it entirely, and instead identifying the rising middle classes and the manor houses of country gentry as the sponsors of this literary movement. The challenge for the historian now lies in reassessing these conflicting analyses, both fashionable and derided, and searching for the possibility of balance between them. In doing so, it becomes clear that the concept of direct influence, through patronage and commission is indeed less convincing than that of the court's promotion of literature through indirect means. Both concepts shall be addressed here.

However, more recent analyses have cast doubt on this image, at times dismissing it entirely, and instead identifying the rising middle classes and the manor houses of country gentry as the sponsors of this literary movement. The challenge for the historian now lies in reassessing these conflicting analyses, both fashionable and derided, and searching for the possibility of balance between them. In doing so, it becomes clear that the concept of direct influence, through patronage and commission is indeed less convincing than that of the court's promotion of literature through indirect means. Both concepts shall be addressed here.

It is important first to define what is meant by the idea of direct patronage in a court setting. Here, it will be taken as active financial support for an artist, enabling the him to focus freely on his art without needing to worry about earning a living. An additional possibility could be the gifting of annuities or support in gaining employment in desirable positions.

Chaucer and Gower: 'court poets'?

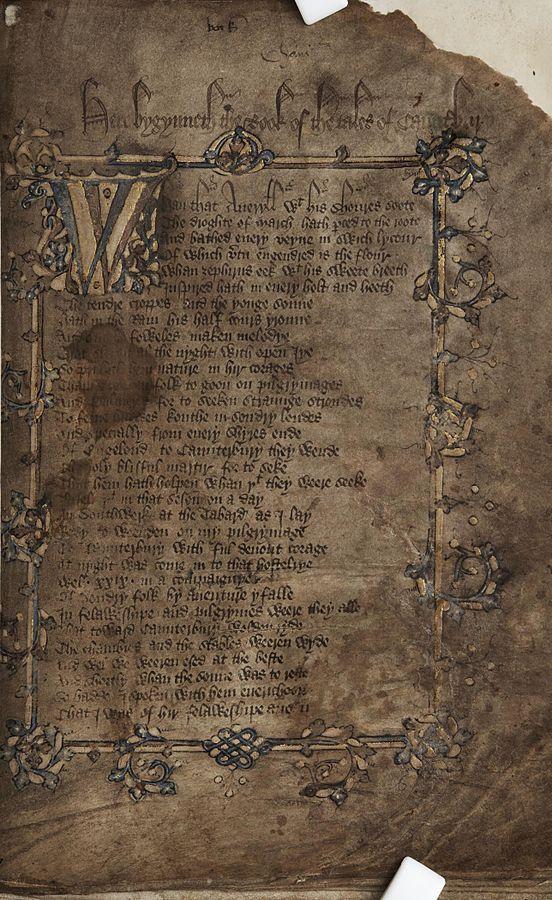

Chaucer has been identified as a 'court poet' due to his regular involvement there and to the frequent references to the aristocracy and court in his works. It has also been suggested that he likely received some of the official positions he held as a result of appreciation of his literary output. Yet this is problematic when his works are considered directly. At the time it was commonplace for any commissioned work to be produced with an image of the artist presenting the finished article to the patron. None of Chaucer's manuscripts carry this image, a fact that makes it far more difficult to believe that his writing was 'made to order', particularly if the suggestion is that he was producing for a member of the court, which would require a great display of deference. Similarly, at no point did he make any definitive statement as to who acted as inspiration for his writing, essentially ruling out the possibility of active noble patronage.

The issue of whether or not Chaucer's success in his official capacity was directly linked to his production of poetry is also far from clear cut. By the time of the death of Edward III in 1377, Chaucer had already been awarded a position as a customs controller and was working closely with courtiers in diplomatic work, most likely fulfilling a secretarial role. This was the case long before the writing of Troilus and Criseyde of Troy. Although not as well known as the Canterbury Tales, it is considered by some to be the better poem. , or any of his other notable and popular pieces. While it is impossible to dismiss entirely the notion that appreciation for Chaucer's literature played a part in his receiving promotions and annuities, it would be far too simplistic to assert a definite link or to argue that the awarding of offices in any way influenced the style of his creative output.

By the time of the death of Edward III in 1377, Chaucer had already been awarded a position as a customs controller and was working closely with courtiers in diplomatic work, most likely fulfilling a secretarial role. This was the case long before the writing of Troilus and Criseyde of Troy. Although not as well known as the Canterbury Tales, it is considered by some to be the better poem. , or any of his other notable and popular pieces. While it is impossible to dismiss entirely the notion that appreciation for Chaucer's literature played a part in his receiving promotions and annuities, it would be far too simplistic to assert a definite link or to argue that the awarding of offices in any way influenced the style of his creative output.

At this point it is worth pausing to consider factors beyond court influence and patronage to explain Chaucer's remarkable literary productivity. External changes in English social, economic and cultural life undoubtedly played a significant role in encouraging writers, especially those who were exploring the new possibilities in vernacular literature. The late-fourteenth century saw a significant rise in the level of lay literacy, particularly in English as opposed to French and Latin, the traditional languages of those considered literate. The ability to read and write had increasingly become seen as vital to success as much in work outside the clerical realm as in it. As a result, more and more members of the gentry were allocating funds for schooling – largely, although not exclusively, for boys – and making provisions in wills for the establishment or maintenance of schools operated by churches, guilds or other local organisations, leading to a huge increase in the number of such operations in this period. As a single illustrative example, figures collected for the York diocese suggest a possible four-fold increase in reading schools between the mid-fourteenth and the end of the fifteenth centuries. One side effect of this growth in literacy outside the clergy and aristocracy was the appearance of a new market for published works of all kinds. Evidence for this greater demand can perhaps be found in the 1373 foundation of a scriveners' guild in London, but is even clearer through examination of personal inventories and wills. Chaucer's works appeared as bequests not only in the wills of the gentry and nobility – Troilus and Criseyde and the Canterbury Tales are found in Sir Thomas Charlton's will, for example – but were also frequently bequeathed by merchants, as in the cases of Londoners John Bromley and William Holgrave who both left copies of the Canterbury Tales. A situation in which the market for creative literary work in English had grown to such an extent surely proved to be a factor in encouraging its production. In light of this fact, Chaucer's lack of a clearly defined patron for his work is far less surprising. If he initially composed his poetry for his own amusement and perhaps for the pleasure of public readings, here was an audience far broader and doubtless more gratifyingly large than any that could be found at court.

John Gower, the other great 'court' poet operating at the time, provides another interesting case for the importance of court patronage. A man of independent means, owning land in East Anglia and Kent, Gower was certainly not reliant on patronage for his living. That being said, his work does show far greater connection with the court than Chaucer's in its dedications and purpose. His Vox Clamantis addresses the problems of the realm directly, as much a didactic piece of political polemic as it is any kind of literary work, demonstrating a personal obsession with the ideas of moral kingship. Gower was a man clearly writing for his own reasons while still engaging with the court environment to which he had direct access. His Confessio Amantis is a clear example of direct commission, being dedicated to Richard II and with the tale of its being requested on the king's barge during a night-time meeting on the Thames. The later alterations made to the Confessio are useful when considering to what extent this commission played in Gower's decision to write the piece. For the later edition, Gower completely removed the dedication to Richard and any suggestion that the work was a completion of an assigned task. This matched alterations he made to Vox Clamantis as well, where the earlier assertion that it was the king's council that was responsible for all of England's ills was changed to identify the king's own undisciplined behaviour and neglect of proper morality as the source of the national malady. Had Gower been reliant on royal patronage when creating and revising his works, it would have been unthinkable that he should have made such damning changes in so unrepentant a manner. Such alterations would become more understandable after Henry IV took the throne, but these appeared far earlier, perhaps as early as 1393 on Bolingbroke's return to England, a full six years before Richard was usurped. It appears that at this time, Gower took on Bolingbroke's livery and therefore reworked his writing to gratify his new patron, and in this way the completed work can be seen as a product of 'the court', influenced not by patronage aimed at promotion of the arts, but as a piece of art born of personal expression in a distinct political and cultural environment.

It is in this sense that the court of Richard II had a clear effect on the development of English literary creativity and achievement, and one without which it is unlikely that the most notable works of the period would have been created in the way they were. Rather than acting as a direct source of financial patronage and commissions, the court environment, its atmosphere, concerns, and ambience, all created a milieu in which varied, experimental artistic endeavour was indirectly fostered. When examined with this in mind, criticisms of the traditional view of the Ricardian court as the focal point of a creative flowering need to be reconsidered.

The role of Richard

Richard's personal interest in literature and the contents of his library are aspects of this question that have attracted wide-ranging opinions. While Michael Bennett has supported a more traditional view, pointing to Richard's receipt of lavishly produced works as gifts, including a beautiful Book of Statutes from around 1389 and a Belleville breviary given as a wedding present by Charles VI of France, Nigel Saul has suggested that Richard was not such a great bibliophile, making a direct comparison between the number of books in his collection – fewer than twenty – and the huge library of Charles V stored in the Louvre. Although the small size of the collection calls into question the extent to which Richard took an active interest in the production of literature, especially when contrasted with his engagement with the visual and architectural arts, its contents are intriguingly varied and can be used to illustrate an artistic atmosphere at court. Within the collection is the original presentation copy of the Confessio Amantis, some Arthurian romances, and a collection of love poetry presented by Froissart, all of which would be expected regardless of Richard's personal level of interest in literature. However, the collection also contains a manuscript that may be the only piece with internal evidence of a direct royal commission.

Although the small size of the collection calls into question the extent to which Richard took an active interest in the production of literature, especially when contrasted with his engagement with the visual and architectural arts, its contents are intriguingly varied and can be used to illustrate an artistic atmosphere at court. Within the collection is the original presentation copy of the Confessio Amantis, some Arthurian romances, and a collection of love poetry presented by Froissart, all of which would be expected regardless of Richard's personal level of interest in literature. However, the collection also contains a manuscript that may be the only piece with internal evidence of a direct royal commission. It is made up of tracts on kingship, something it shares with the Confessio, and also contains a piece on geomancy and its applications. Another manuscript is a compilation of treaties, letters and an account of Edward I's 1296 campaign in Scotland.

It is made up of tracts on kingship, something it shares with the Confessio, and also contains a piece on geomancy and its applications. Another manuscript is a compilation of treaties, letters and an account of Edward I's 1296 campaign in Scotland. While such texts may not be easily defined as 'literature' in the sense of creative art, they point to Richard's interests and concerns, which were surely not unknown in the court itself. They also demonstrate Richard's interest in documentation and the written word, whether this extended to a fondness for fiction or not. In this context, John Gower's story of his boat ride with the king makes much sense. Whether true or not – and there is no real reason to question it – there would have been no reason to tell it had the image of the king engaging a poet on his barge not been a believable one. It thus indicates something of the monarch's attitude towards the creative arts, an attitude which may have been reflected in the character of the court.

While such texts may not be easily defined as 'literature' in the sense of creative art, they point to Richard's interests and concerns, which were surely not unknown in the court itself. They also demonstrate Richard's interest in documentation and the written word, whether this extended to a fondness for fiction or not. In this context, John Gower's story of his boat ride with the king makes much sense. Whether true or not – and there is no real reason to question it – there would have been no reason to tell it had the image of the king engaging a poet on his barge not been a believable one. It thus indicates something of the monarch's attitude towards the creative arts, an attitude which may have been reflected in the character of the court.

The presentation of the Confessio in English rather than Latin or French is also extremely telling, as is the freedom with which Chaucer felt able to use the vernacular in his writing. An acceptance of English for artistic purposes within the court was surely impetus enough for experimentation and the development of the new wave of poetry. Although it has been noted that Chaucer's manuscripts lack a standard presentation image, a copy of Troilus and Criseyde at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, is fronted by an image of the poet reading to a court audience. If this is to be seen as Chaucer himself and the manner in which works were shared, it indicates an openness toward, and an appreciation of, the new style of literature. Engaging in the creative process within this accepting environment may have been all the encouragement required for writers, with direct patronage largely unnecessary. If the court can be seen as a 'cultural construct' rather than a clearly defined institution, it would have been changeable, fluid and open to interaction with myriad ideas from many different sources. What better surroundings could be imagined for artistic inspiration and influences than these?

If this is to be seen as Chaucer himself and the manner in which works were shared, it indicates an openness toward, and an appreciation of, the new style of literature. Engaging in the creative process within this accepting environment may have been all the encouragement required for writers, with direct patronage largely unnecessary. If the court can be seen as a 'cultural construct' rather than a clearly defined institution, it would have been changeable, fluid and open to interaction with myriad ideas from many different sources. What better surroundings could be imagined for artistic inspiration and influences than these?

Richard's was a court unlike any that had come before in England: far less martial in its character, self-consciously more refined in the French style, dedicated to a 'cult of good manners'. Here was an environment in which, without any sense of incongruity, traditional Arthurian romances and religious tracts were joined by The Forme of Cury, a celebrated cookbook, and a translation into English of a scientific tract on urine, commissioned by Richard so that laymen might benefit from it. Writing in this air of the celebration of the new and the novel, combined with a greater looseness in composition allowed by working in English – a language which did not have the formalised and more rigid stylistics and structures to be found in an established literary language like French – poets such as Chaucer and Gower cannot have helped but be driven forward in the creation of something truly remarkable. Without such indirect influence, the great revolution in English literature and the treasures it gifted may never have seen the light of day.

Here was an environment in which, without any sense of incongruity, traditional Arthurian romances and religious tracts were joined by The Forme of Cury, a celebrated cookbook, and a translation into English of a scientific tract on urine, commissioned by Richard so that laymen might benefit from it. Writing in this air of the celebration of the new and the novel, combined with a greater looseness in composition allowed by working in English – a language which did not have the formalised and more rigid stylistics and structures to be found in an established literary language like French – poets such as Chaucer and Gower cannot have helped but be driven forward in the creation of something truly remarkable. Without such indirect influence, the great revolution in English literature and the treasures it gifted may never have seen the light of day.

Things to think about

- Did Richard II actually like books?

- How much did Richard II personally influence the development of literature?

- How important were Chaucer and Gower to English literature?

- Were Chaucer and Gower 'court poets'?

- What was the influence of the gentry in promoting literature?

- How has the English language developed as a result of literature in the fourteenth century?

Things to do

- The great works of literature from the fourteenth century are still readily available to read. Look through Chaucer and Gower to understand the way language and story-telling developed.

- The poets of the late fourteenth century are said to have influenced English literature ever since. Consider later texts, from Shakespeare to Harry Potter, to see what links you can find.

- The late fourteenth century was a time of artistic flowering across the disciplines. Study the wider cultural contexts, including developments in art and architecture, to get an deeper understanding of the period.

Further reading

The best way to understand the literature of the age is to read it. There are many published collections of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, and others available on the market, from cheap Penguin editions to expensive academic versions.

Without doubt, the best book on Richard II is still Nigel Saul's Richard II. This is an essential read for anyone wanting to understand the king and his court.