With so many podcasts available at the moment, it takes a lot to stand out from the crowd. But there's one new one that's going from strength to strength: Mariner's Mirror. We caught up with its creator, Dr Sam Willis, while he was filming at the Science Museum's National Collections Centre to find out what it's all about.

What is the Mariner’s Mirror podcast?

The idea for it came up during lockdown. Everyone was doing podcasting stuff, so I spoke to the guys at the Society for Nautical Research who've been publishing the Mariner's Mirror – an academic journal on maritime history – for over a century. And I said, ‘Look, it's time to do something different.’ So we launched it a couple of years ago now, and it's been fantastic. We've just won a Certificate of Merit in the Maritime Media Awards for the best use of digital media. And we have the podcast in which I interview all sorts of people, academics and non-academics, interested people and shipwrights – people who are involved practically in the maritime world and who have an interest in maritime history.

Not only have we been doing audio stuff, we've also been doing some fantastic video content. The challenge here was to make the maritime world interesting to people who've not come across it before, with a blank slate on what we could do. One of the first things we did was to use AI to recreate Nelson's face from a plaster mask that looks like a death mask, but was taken during his life, which is incredible. Working with digital artistry and AI to see what it showed us was really, really entertaining.

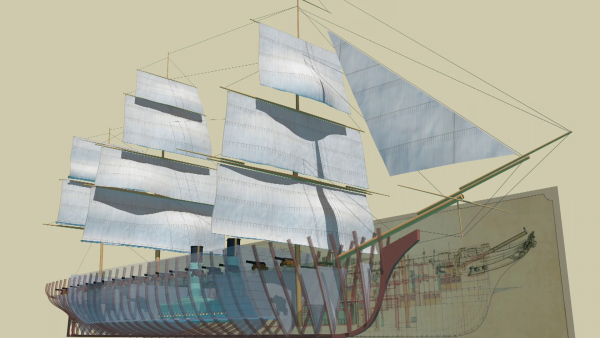

We've also animated ship plans, which are brilliant. I was working with the National Maritime Museum and there are some hugely complicated, beautiful drawings which make no sense to anyone unless they're trained naval engineers. It's a real problem when so much money is spent every year curating these things, but then no-one uses them and no-one understands them. But we've grown 3D animations out of the drawings: you isolate particular lines or particular pieces of the engine, and then you animate it so it looks 3D and makes sense, and then it can sink back again into the drawing. So it's a way of providing a guide to a technical drawing which would otherwise be incomprehensible, and it's particularly well suited to maritime and naval history.

One of the best ones I was working on was inspired by the Lloyd's Register Foundation's collection, and they've got something like 2,000 boiler plans. I looked at them and thought, 'I don't know what to do; what is that?!' They said they didn't really know either. So I collaborated with a consultant, who helped me understand how ships' boilers functioned and then an animator who had done some maritime work before. And it now makes perfect sense to me: we've gone from a beautiful technical drawing which looks weird and is quite visually interesting to appreciating exactly what it shows and how it's important. That's been very enjoyable.

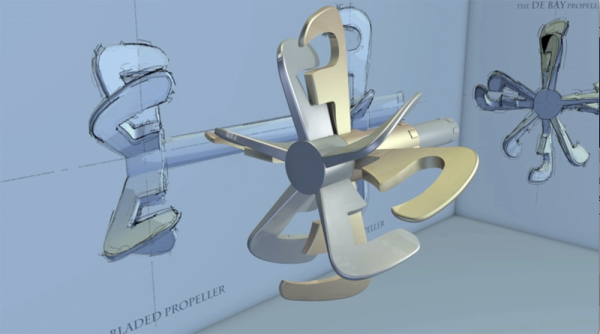

Using these animations, the podcast did a ship's boiler from the nineteenth century. We then did HMS Warrior, one of the most important warships ever built, from the 1840s: it was made out of iron and had a steam engine in it. Warrior's ship plan is mind-blowing because for the first time, they're not just showing timber, they're showing serious steam machinery as well as guns, which means it's incredibly complicated. So making sense of that was fun. Then we did the K-class submarines, which are a fascinating moment in the history of submarine development. It's an insane idea, but they put steam engines on submarines – how does that work!? And the submarines were enormous: these are genuine monster submarines from the First World War, and they were a bit of a disaster. But again, the ship plans of submarines are somehow even more complicated than for ships, and it’s been a fabulous project making sense of them: I've learnt an enormous amount and it's been hugely successful, particularly on social media. We've had an animation of a weird nineteenth-century propeller that's been seen 4.5 million times on Instagram.

The podcast has done all sorts of other shorts as well. One that sticks out is a bizarre nineteenth-century ship that was built to transport Cleopatra's needle from Alexandria to London, which you can still see on the banks of the Thames. They built this weird iron ship around this ancient Egyptian obelisk. So, we've discovered a real appetite for people to see curious visual things and the podcasts are going from strength to strength. It's got a real international footprint with over 350,000 downloads, and it's great.

Can viewers contact you with ideas?

I'm really keen to work with people who've got ideas. In fact, I was speaking to the bloke who runs the Facebook Patrick O'Brien Appreciation Society – Patrick O’Brien was the author of a series of extremely popular nautical novels set during the Napoleonic Wars – and I thought, ‘I bet they've got a thing or two to say about the past.' So I'm very interested in working with them, and I want to ask them what they would like to hear and I want to interview a few of them to find out what they like about Patrick O'Brien. I'm also interested in hearing from fans of any aspect of maritime history. If you're a Titanic nut, or Titanorak I think is the actual word, or whatever it is – everyone has their own little bit of interest – and I'd love to hear from anyone. It's the way that you uncover new aspects of history. I'm on a firm mission to take history out of the grip of historians, and allow non-academics to call themselves historians.

How long does it take to do a podcast?

Some of the podcasts are just plain interviews – me chatting with people. I've been all over the place, just done a series in Sweden and one in Australia, so I've been travelling around meeting wonderful people. Actually, one of the most interesting was a discussion with a bloke who's a shipwright who’s renovating a nineteenth-century pearling lugger in Brisbane. It's a beautiful ship, and as they were clearing out the hull while I was interviewing them, they found a massive pearl shell, cleaned it all off and the gleam came through for the first time in over a century. It was fantastic.

While the majority of them are interviews, we're also doing some much more complicated things. We're currently using actors to help recreate the several days of the Titanic inquiry, which has recently been transcribed. After Titanic went down, there was an inquiry in the States and an inquiry in the UK. People had a lot of vested interest in what the hell went wrong – politicians, people assuring the safety of ships – and there was a lot of in-depth questioning in a proper courtroom. It was all quite frightening. So this is historical gold dust. It's fantastic because everyone knows what happens, right? But there’s something about hearing the people interviewed: we hear from a lady who was a nurse for some young kids, we hear from a lady who was a first-class passenger, and then we hear from one of the most senior surviving officers. One of the guys that we're recreating was a Scouser and a stoker, and he has no interest in it at all – he's quite dismissive and he's quite cross that he's been made to stand up and answer to all of these posh people. He just wants to be left alone. It's comedy genius; it's absolutely brilliant. But obviously that takes much longer to make and recreate. We've also done several first-hand accounts of naval battles, which have been recreated from the perspective of the person writing the diary, which has been really entertaining.

Of course, you have the animations for them as well. That looks like it's quite complicated to do.

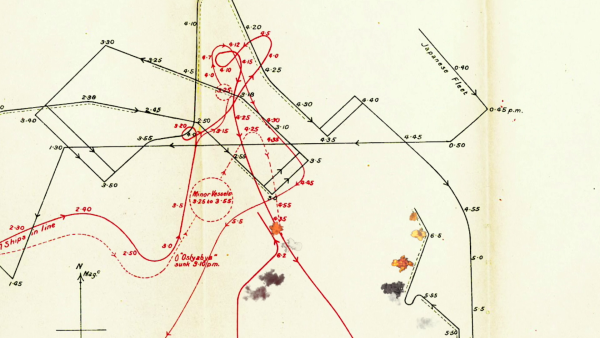

It's very complicated. I've been working with people I've never worked with before and it's wonderful. When you're animating something that doesn't exist, you've maybe got the original plans, but the rest of it's imaginative – these guys are artists as much as they're technical animators. Sometimes we also work with something that does exist – battle plans are an example. There's one which is a hand-drawn battle plan of the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, which is when the Japanese had a big old fight with the Russians. The Japanese significantly won, and a British guy was onboard and made a hand-drawn sketch of what was going on. It is very complicated. All naval battle plans are: it just looks like loads of squiggles. And so we used the sketch as a starting place and animated it: you start with a blank page – like you're drawing it – and then there are explosions and things make sense as it goes on. I don't think anyone's ever done that before. That's the whole point of why I'm enjoying it so much and why it's so good: we are constantly doing things that have never been done before, just to see what happens.

What are looking at doing next for the podcasts?

We're doing a series on maritime China, which is absolutely fascinating, talking about all sorts of things. There's actually, interestingly, a wonderful collection of Chinese junks here at the Science Museum National Collections Centre, called the Frederick Mayes Collection of Ship Models. It was created by a guy who was director of customs in Hong Kong, and who had a wonderful collection of ship models made by Chinese craftsmen from Hong Kong and Guangzhou. Then there’s HMS Poseidon, which was a British submarine that sank on the China station and was secretly salvaged by the Chinese, which was only discovered when divers went down to find it. They knew exactly where it went down, but it wasn't there. So they discovered it was salvaged, but no one knows what happened to it. That's an amazing story, particularly for the people who survived it. Surviving submarine sinkings is very rare, but those who do are often ruined for the rest of their lives because of the medical problems that they then suffer from. And that certainly happened in this case. There are several other episodes about all sorts of aspects of Chinese history: the maritime Silk Road; Zheng He, the great Chinese explorer of the fifteenth century as well. So that's coming up, which I'm very excited about.

How frequently do the new podcasts go out?

At least once a week. Sometimes for a series – we've just done one on maritime Australia – we're releasing maybe two or three a week, just to get through all of the ones we made, because I had such a wonderful time and I kept meeting more and more interesting people. Every time I met someone else, they had something interesting to say. My favourite episode out of that is coming soon, which is on ‘Aborigines and the Sea’, and that's fascinating. They've got a little exhibition on Aboriginal rock art in Western Australia which depicts some Aboriginal vessels, although the majority are non-Aboriginal, and the fantastic team at the Museum of Western Australia have been trying to identify the vessels that have been drawn. It's really cool.

What's your all-time favourite Mariner’s Mirror podcast?

It would probably be the pearling one. But also I've always been interested in ship models, which has led to this great new project I'm doing called Maritime Innovation in Miniature, filming the world's best ship models using the latest camera equipment. We were given access to the National Maritime Museum's collection of ship models where I spoke with a guy called Simon Stephens, who is the conservator of ship models there. That was fascinating: the variety of them, filming and talking to someone who was so knowledgeable about it, and being given the unique access as well is something I'll never forget.

Are there any podcasts you would love to do, if there were no restrictions?

I would like to go to Nova Scotia and the north-east coast of America. I think that's fascinating. I’d like to find out about fishing: fishing is really interesting, with lots of very salt-of-the-earth, ordinary people risking their lives. But you can also talk about the changing marine environment. I love more than anything going to a pub and seeing a photo of a bloke with a fish that's bigger than him because it makes you realize how much the environment's changed. Or I'd do something in the Arctic and get really involved in how things like how the Northwest Passage is changing and who's navigating it now, and how it was different in the past. I think it is quite interesting actually that people are paying much more attention to Indigenous views on certain parts of the world and the Arctic is one of them: they eventually found the vessel Sir John Franklin used to attempt the Northwest Passage, HMS Terror, because they decided to go and ask the people who lived there if they knew where it was. Brilliantly, it was in Terror Bay – I could have worked that out! I think the Arctic, and the way that the world's changing up there, is fascinating.

How can people find the Mariner's Mirror podcast?

You can get it wherever you get your podcasts. I'd particularly get people to go and look at the YouTube channel and also the Society for Nautical Research is a brilliant website. You can find all of the animations and all of the audio in one place there. You can also search for the Mariner's Mirror Pod on Instagram, or the Society for Nautical Research on Facebook, but really the Mariner's Mirror Podcast on YouTube is the place to go.