Key facts about the history of climate change

- Climate changed massively during the Stone Age

- The Stone Age saw at least three big ice ages

- Sometimes Britain was too cold for humans to live in

- There were also a number of warm periods, or interglacials

- The land, plants and animals changed to suit the climate

Climate changed dramatically during the Stone Age, from warmer than today to much colder. There were a number of ice ages, where glaciers expanded down from the north and sometimes covered much of Britain, making it impossible to live there.  ... and 12000 BP, it has been estimated that Britain was inhabitable for only a quarter of the time (or about 140,000 years). During an ice age, the weather would often be much drier, as water that today comes down as rain was frozen in glaciers. With so much water trapped in ice sheets and glaciers, sea levels would drop so land which now is under the sea would become dry and people (and animals) would be able to walk across it. The land immediately near the ice sheet could become a barren and treeless place with polar desert or tundra . There could be bogs and huge lakes near the ice sheet, created by meltwater during the summer, and these would allow short plants, such as grasses, shrubs, herbs and mosses to grow. Some animals relied on this environment to live, such as the arctic hare and mammoth.

... and 12000 BP, it has been estimated that Britain was inhabitable for only a quarter of the time (or about 140,000 years). During an ice age, the weather would often be much drier, as water that today comes down as rain was frozen in glaciers. With so much water trapped in ice sheets and glaciers, sea levels would drop so land which now is under the sea would become dry and people (and animals) would be able to walk across it. The land immediately near the ice sheet could become a barren and treeless place with polar desert or tundra . There could be bogs and huge lakes near the ice sheet, created by meltwater during the summer, and these would allow short plants, such as grasses, shrubs, herbs and mosses to grow. Some animals relied on this environment to live, such as the arctic hare and mammoth.

Times in between the ice ages are known as interglacials, and during these periods the climate warmed and sea levels rose. Trees would come back to the land along with a great variety of animals (and humans). Interglacials could have temperatures that were warmer than today, and we can see this in the sorts of plant and animal remains that are found. In Britain, hippo and monkey bones have been found. Climate could change very quickly, with huge drops or rises in temperature happening within 10 years.

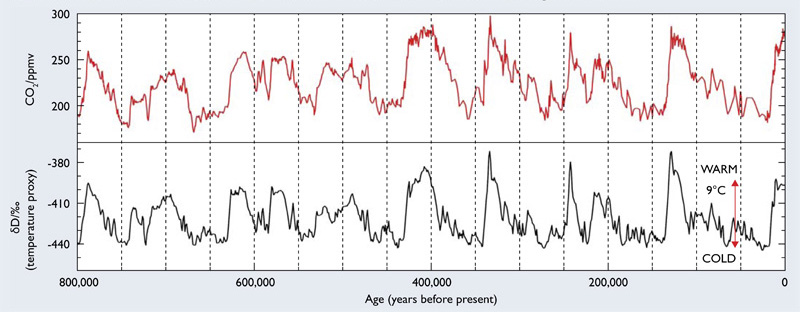

Scientists used to think that there had been only three main ice ages, with four interglacials in between. With more study we are finding that this has been too simple, and it is actually much more complicated. At the moment, we think there were over 20 big climate changes in Britain within the last 900,000 years, and these were often different from other parts of the world. An interstadial is a time during an ice age when the weather warms up, and a stadial. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'.. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'.. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. is a cold period within an interglacial . These stadials and interstadials are much shorter than ice ages and interglacials, and at most will cover about 10,000 years.

Sudden changes in temperature, even if they were small, could have a massive impact on the people living through it, particularly if they were living in places that were almost too hot or cold anyway. This would have led to migration and changes in the size, structure and purpose of the communities (where once they might have been at a place all the time, after a drop in temperature they could only visit for hunting during the summer).

What causes worldwide climate change?

Large climate change events in the past have usually been caused by the relationship between the Earth and the Sun, which is affected by the gravity of other planets in the solar system, particularly Jupiter. There are three ways this relationship can change, and when more than one of these happens at the same time, we get a bigger change in the Earth’s climate. These reasons are:

- The Earth’s orbit around the Sun is not round but slightly egg-shaped, making a pattern of climate change every 100,000 and 400,000 years. This is called the Earth’s eccentricity .

and happens around 3rd January. At its farthest point, the Earth is 152.1 million km away, around 4th July, and is known as the aphelion .

and happens around 3rd January. At its farthest point, the Earth is 152.1 million km away, around 4th July, and is known as the aphelion . - The Earth slightly changes its angle (or tilt), which gives us changes over a 41,000 year pattern.

This is called the Earth’s obliquity .

This is called the Earth’s obliquity . - The Earth wobbles (about its axis. The term 'Axis' helps differentiate them from the Allied powers (which included Britain and America). . The term 'Axis' helps differentiate them from the Allied powers (which included Britain and America). . The term 'Axis' helps differentiate them from the Allied powers (who included Britain and America). as it spins) giving us climate changes on a 19,000 and 23,000 year cycle. This means that seasons will shift over time and cause the solstices and equinoxes to move. This is called the Earth’s precession, or the ‘Precession of the Equinoxes ’.

There are other reasons for changes in climate, such as eruptions from volcanoes or maybe changes in the Sun’s activity (such as sun spots). Feedback loops, where the effects of something make that thing still bigger, would also have played a role in changing the climate of the planet, often quite quickly. The movement of the Earth’s plates (tectonics) have also had a huge impact on cooling the planet over the last 55 million years.  Ocean currents help to warm or cool the climate, either by bringing warm water from the tropics to higher latitudes (places close to the poles), like the Gulf Stream does at the moment, or by bringing cold water from the poles closer to the equator. Scientists are worried that modern humans are changing the climate now by burning too many things that contain carbon, such as fossil fuels, and releasing too many climate-affecting elements into the environment. Recent research has found that the level of carbon in the air is important for new glacial periods to start.

Ocean currents help to warm or cool the climate, either by bringing warm water from the tropics to higher latitudes (places close to the poles), like the Gulf Stream does at the moment, or by bringing cold water from the poles closer to the equator. Scientists are worried that modern humans are changing the climate now by burning too many things that contain carbon, such as fossil fuels, and releasing too many climate-affecting elements into the environment. Recent research has found that the level of carbon in the air is important for new glacial periods to start.  This research suggests that recent human civilisations have delayed the next ice age, which should have started in the last two thousand years, by up to 100,000 years.

This research suggests that recent human civilisations have delayed the next ice age, which should have started in the last two thousand years, by up to 100,000 years.

Geological periods and epochs

The history of the Earth is split into geological periods. Each geological period is very big, and can last for millions of years. The main period prehistorians are interested in is the Quaternary , which began 2.58 million years ago, and which we are still in today. The period before that is the Neogene , which started about 23.3 million years ago. Some of our very early ancestors lived in this time. These geological periods are split into smaller parts, known as epochs. The epochs that most prehistorians are interested in are:

- Pleistocene with many ice ages and interglacials. It ran from 2.58 million years ago until 11,700 years ago. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'.. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. with many ice ages and interglacials. It ran from 2.58 million years ago until 11,700 years ago. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'.. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. with many ice ages and interglacials. It ran from 2.58 million years ago until 11,700 years ago. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. – this is the first epoch

. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. of the Quaternary, and covers the time of the most recent ice ages and interglacials.

. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. of the Quaternary, and covers the time of the most recent ice ages and interglacials.  At the beginning of the Pleistocene, Britain was probably an island, surrounded by warm seas. Although there had been ice in the Antarctic (South Pole) for millions of years, there was not much ice in the north, making sea levels much higher than today. As the weather changed, ice started forming in the north, and sea levels dropped so that more land appeared in Britain (such as modern day Kent). Rivers flowing into the North Sea left silt around the coast, which made more land between Britain and the continent. By 1.8 million years ago, it would have been possible to walk between Britain and Belgium or France. At the moment, we think humans first came to Britain during the Middle Pleistocene, about one million years ago.

At the beginning of the Pleistocene, Britain was probably an island, surrounded by warm seas. Although there had been ice in the Antarctic (South Pole) for millions of years, there was not much ice in the north, making sea levels much higher than today. As the weather changed, ice started forming in the north, and sea levels dropped so that more land appeared in Britain (such as modern day Kent). Rivers flowing into the North Sea left silt around the coast, which made more land between Britain and the continent. By 1.8 million years ago, it would have been possible to walk between Britain and Belgium or France. At the moment, we think humans first came to Britain during the Middle Pleistocene, about one million years ago. - Holocene – the Holocene comes from the Greek and means ‘completely new’. It is the epoch we’re in now, and started 11,700 years ago (at the same time as the Mesolithic of the Stone Age'. of the Stone Age'. of the Stone Age'. started), at the start of the most recent interglacial.

- Anthropocene... - some people are suggesting a new epoch, called the Anthropocene, to mark when humans started affecting the environment on a visible scale. As well as debating whether it should count as an epoch, they are also debating when it started (the Neolithic, the Bronze Age, which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE., or later, such as when we started using atomic energy).

Climate in Britain during the Pleistocene epoch

Humans (so far as we know) first arrived in Britain in the middle of the Pleistocene epoch, about a million years ago, after the seas had dropped low enough to walk from the continent. Although we know that climate in Britain before and after this point was very complicated, a lot of people still refer to the old ice age and interglacial stages, so it can be helpful to know a little bit about them.

- Cromerian stage – the Cromerian stage started 866,000 years ago, of which the Pakefield interglacial and the Happisburgh glaciation are parts (see below). Following the retreat of the ice in about 600000 BP there was a warm period which could have lasted for about 100,000 years. During this time many of our rivers, such as the Severn and the Bristol Avon, didn’t exist. Other rivers, such as the Thames, were not where they are today. (which lasted from about 34 million years ago until 23 million years ago), and it possibly drained from as far west as Wales. By the middle of the Pleistocene it was draining from near the Cotswolds, heading east and then north east, reaching the North Sea in Norfolk. However, during times of lower sea levels, it also sometimes became a tributary of the Rhine system. There were also some big rivers that now don’t exist, including the Mathon (which flowed southwards through Herefordshire) and the Bytham , which was huge, running 200 miles from the Midlands southwards and then eastwards, finishing in a massive delta in East Anglia. Many important archaeological sites have been found along the course of this river.

- Pakefield interglacial – Within the Cromerian stage were a number of glacial and interglacial periods. One important period of glaciation was the Happisburgh interglacial.

The Pakefield interglacial is the name given to the time before the Happisburgh glaciation. The climate was similar to that of the Mediterranean today: summers would have been warm and dry and winters wet. Average temperatures in July are thought to have been between 18°C and 23°C (compared with 15°C today) and the plants and animals found show that temperatures in winter would not have dropped below freezing. There is evidence that hippos lived in Britain, as well as elephants, hyaenas, and deer. Its name comes from the animal and plant finds from an archaeological site in Pakefield in Suffolk, which have been dated to at least 700,00 years ago.

The Pakefield interglacial is the name given to the time before the Happisburgh glaciation. The climate was similar to that of the Mediterranean today: summers would have been warm and dry and winters wet. Average temperatures in July are thought to have been between 18°C and 23°C (compared with 15°C today) and the plants and animals found show that temperatures in winter would not have dropped below freezing. There is evidence that hippos lived in Britain, as well as elephants, hyaenas, and deer. Its name comes from the animal and plant finds from an archaeological site in Pakefield in Suffolk, which have been dated to at least 700,00 years ago. - Happisburgh glaciation – It has been suggested by geologist Jim Rose that the Happisburgh glaciation happened about 650,000 years ago. He thinks that an ice sheet pushed south from Scotland into the Midlands and East Anglia, and this has an important effect on dating finds, pushing the dates back by up to 200,000 years.

analysis, which uses sediment from the ocean floor to tell us about global climate change, backs up this theory of a cold period.

analysis, which uses sediment from the ocean floor to tell us about global climate change, backs up this theory of a cold period.

Ice limits of the Anglian, Wolstonian and Devensian ice sheets, courtesy of Chiltern Archaeology - Anglian Ice Age ran from about 480,000 to 423,000 years ago. It was the most severe ice age Britain has experienced in the last 2 million years. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. – the ice began to arrive from Scandinavia about 480,000 to 470,000 years ago, although some people think it might be a little later. This is the worst ice age Britain has had in the last 2 million years, when it was covered by an ice sheet which reached as far south as the Thames and north London, and pushed the Thames into its current position. The ice stretched west across to Bristol, but didn’t go over most of Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. It overran the Bytham River, which never reappeared. South of the ice would have been huge lakes, such as Lake Harrison (which stretched over Leicester, Coventry, Rugby and Leamington), filled by spring thaws and ice-dammed rivers. With so much ice over Britain, it would have been impossible for humans to live there. Even where there was no ice, it would still have been far too cold and windy (glaciers cause a lot of wind). The Anglian ice age lasted about 60,000 years, and the ice started to retreat about 423,000 years ago.

- Hoxnian interglacial – this lasted from about 410000 BP to 380000 BP. The climate warmed, and July temperatures were on average 18°C, which is three degrees warmer than today. With the warmer climate, trees and a wide range of animals returned. These included elephants, rhinos and lions (which were one and a half times bigger than modern African lions). Humans also came back to Britain, which we know from the items they left behind, such as burnt remains and tools. being from around 250,000 years ago) and about 40,000 years ago. They lived alongside modern humans and interbred with them. being from around 250,000 years ago) and about 40,000 years ago. They lived alongside modern humans and interbred with them. being from around 250,000 years ago) and about 40,000 years ago. They lived alongside modern humans and interbred with them. characteristics (it has been thought that proto- Neanderthals emerged about 450,000 years ago and that they only fully emerged as a distinct species about 250,000 years ago. However, new genetic research from a skeleton found in a cave in northern Spain controversially suggests that Neanderthals developed 700,000 years ago).

- Wolstonian stage – starting about 380,000 years ago, the north of Britain again became covered in ice. There were considerable changes in temperature during this ice age, which had two warmer periods (or interstadials) within it. The first is sometimes called the Purfleet interglacial was an interstadial around 320,000 years ago, during the Wolstonian Stage. See 'A Brief History of Climate Change'. around 320,000 years ago, which was the last time that macaque monkeys were found in Britain. There was another warm phase which happened between 250,000 and 200,000 years ago, with an intense cold snap in the middle, around 230,000 years ago. After 200,000 years ago, the climate became very cold again for almost 70,000 years, and seems to have forced humans out of Britain. These Neanderthals went south to warmer refuges (or refugia ) in what is now mainland Europe.

- Ipswichian interglacial – following the end of the last glacial period of the Wolstonian stage around 130,000 years ago, the climate warmed again (although it experienced a number of stadials) and the temperature in Britain was at least 1°C warmer than it is today: trees grew in places that today are tundra, and hippos could be found in the Thames. The rising temperatures led to a rise in sea levels, and Britain became an island again. It is thought this stopped humans from returning. The Ipswichian didn’t last for long, and by 115,000 years ago, we started entering another ice age.

- Devensian Ice Age – The Gulf Stream, which had been pushing warm water from the tropics to Britain switched about 115,000 years ago, and started pulling colder water down from the Arctic, which could even have led to icebergs in the Mediterranean. The temperature fluctuated for 35,000 years, with effects becoming really noticeable about 90,000 years ago. The waters of the Channel retreated so that by 100,000 year ago Neanderthals were back in Britain and modern humans first arrived (about 30,000 years ago). At this point temperatures in southern Britain reached about 10°C in summer and -10°C in winter. However, with the ice sheets coming further south, the habitable land also retreated southwards so that by about 25000 BP Britain was again abandoned for a stretch of almost 10,000 years. By 16000 BP, conditions eased a little and a few groups came back.

- Last Glacial Maximum – The Last Glacial Maximum (where the ice sheets were at their biggest) was around 21000 BP in Britain.

Much of Britain was covered with a sheet of ice almost a mile thick, from Northern Ireland through the Midlands to the Wash in the east. Between the British and Scandinavian ice sheets was 70 miles of polar desert. Sea levels sank by 125-150m (from the present level), and the Channel retreated, leaving just a river with its tributaries the Thames, the Rhine and the Seine. The land immediately south of the ice became tundra, whipped by strong cold winds.

Much of Britain was covered with a sheet of ice almost a mile thick, from Northern Ireland through the Midlands to the Wash in the east. Between the British and Scandinavian ice sheets was 70 miles of polar desert. Sea levels sank by 125-150m (from the present level), and the Channel retreated, leaving just a river with its tributaries the Thames, the Rhine and the Seine. The land immediately south of the ice became tundra, whipped by strong cold winds.  complex in the northern hemisphere and was formed of 8 million cubic miles of ice (six times the size of the Scandinavian ice sheet) in north-eastern America.

complex in the northern hemisphere and was formed of 8 million cubic miles of ice (six times the size of the Scandinavian ice sheet) in north-eastern America. - Windermere (Late Glacial) – was a warmer period during the Devensian ice age. It lasted from c.90000BP until 11600BP (or 9600BCE). Greenland ice cores show a dramatic period of warming, when much of the Atlantic ice melted in just five years. As the temperature warmed, the land ice retreated and southern Britain became inhabitable, although there was still permanent ice in western Scotland. Sea levels rose again (to 75m higher than at the LGM ), turning the Channel into a bigger river and the northern part of the North Sea returned. Temperatures in summer could have matched those in Britain today, although winter temperatures would have been much colder, and the climate would have been much drier. It is likely, given the climatic conditions and the species of animal and plant excavated, that it would have been grassland, with bushes and shrubs at lower levels, and birch and similar trees along rivers and valleys. Later in the interstadial, the climate got wetter and summer temperatures dropped by as much as 4°C. During the interstadial, large mammals returned to Britain, followed by ice age hunters, and there is evidence that humans came back to Britain around 15,000 years ago.

- Younger Dryas (also known as the Loch Lomond phase) – Around about 13000 BP (or accurately c.10900 BCE), the climate cooled quickly, dropping about 15°C in less than 30 years (and some people think within 10 years). With winter temperatures as low as those in the Last Glacial Maximum, ice sheets again came further south into central Scotland, and the land south of it turned to tundra. There was winter sea ice as far south as Spain. It is thought the Younger Dryas was caused by the Gulf Stream stopping, possibly as a result of large amounts of fresh melt water (from ice melting during the Windermere interstadial) entering the sea and disrupting the current.

We don’t know what effect this had on humans, but it is possible that humans still visited during summer months, perhaps following the herds of reindeer.

We don’t know what effect this had on humans, but it is possible that humans still visited during summer months, perhaps following the herds of reindeer.  In about 9600BCE, temperatures warmed as quickly as they had fallen (to a point where temperature was warmer and wetter than it is now) and Britain became more habitable again. This is when Britain entered the Holocene epoch.

In about 9600BCE, temperatures warmed as quickly as they had fallen (to a point where temperature was warmer and wetter than it is now) and Britain became more habitable again. This is when Britain entered the Holocene epoch.

The Holocene climate

The start of the Holocene was a period of rapid warming and gave the landscape the general shape that we see today (such as mountains, valleys, and erratics). Isostatic uplift (where the land rises after the weight from all the ice is gone, rather like a stress ball that returns to its original shape after it has been squeezed) had the land returning to its full height, quickly at first and slowing over time. Since the end of the last ice age, the land in Canada has risen by 900m, Scandinavia by 700m and eastern Scotland by 250m.

Sea levels also rose, eventually turning Britain back into an island. , and is still happening today: in the south of England it is estimated that sea levels are rising by about 2mm per year (relative to land rise), and it has been estimated (as a generalisation, as sea levels against isostatic uplift varies from place to place) that between 5500BC and 2000BC levels rose by 7m, with about a 1.5m rise between 2000BC and today. Ireland finally became separated from mainland Britain c.9000BCE, but we’re not sure when the water rose so high that the swampy marshland between Britain and the Continent became impossible to cross. People used to think it happened somewhere between 7500BCE and 6500BCE, although new studies using marine life suggest this is too early. These studies say that it happened between 5800BCE and 5400BCE, and some people think that the Channel and the North Sea might not finally have joined until 3800BCE.  As late as the fifth millennium BCE some parts of Doggerland (a fertile and wooded stretch of land linking Britain to the Continent from Calais to Denmark) may have been above water, and there may have been other islands.

As late as the fifth millennium BCE some parts of Doggerland (a fertile and wooded stretch of land linking Britain to the Continent from Calais to Denmark) may have been above water, and there may have been other islands.  , five miles off the coast of Kent, were only submerged during the 11th century (before that, some say they were walled and farmed), but can still be walked on (with care) at ebb tide today. We also don’t know for sure whether the Channel appeared quickly, made by a rush of water like the one that possibly filled the Black Sea, or slowly.

, five miles off the coast of Kent, were only submerged during the 11th century (before that, some say they were walled and farmed), but can still be walked on (with care) at ebb tide today. We also don’t know for sure whether the Channel appeared quickly, made by a rush of water like the one that possibly filled the Black Sea, or slowly.  One guess says that the waters came at 200 yards a year, which would take the Channel a little over 180 years to be made.

One guess says that the waters came at 200 yards a year, which would take the Channel a little over 180 years to be made.  The last land connecting Britain with the continent would have been between East Anglia and the Low Countries .

The last land connecting Britain with the continent would have been between East Anglia and the Low Countries .

The weather was at its best between 9000BCE and 5000BCE (which is known as the Holocene Optimum), when the temperature was warmer and wetter than today.  (c.9600BCE to 8800BCE) which was cold and dry; 2) the Boreal (c.8800BCE-5800BCE) which was a warm and dry period; 3) the Atlantic period (c.5800BCE-4000BCE) which was warm and wet; and 4) the Subboreal (c.4000BCE-2500BCE) when it was drier and cooler than the Atlantic, but still warmer than today. There is a further subdivision, the Subatlantic , which started around 2500BCE and is ongoing today. It is slightly cooler than the Subboreal and Atlantic periods. The ice age steppe (grassland) animals such as mammoth either died out or moved away as woodlands grew over huge parts of the country.

(c.9600BCE to 8800BCE) which was cold and dry; 2) the Boreal (c.8800BCE-5800BCE) which was a warm and dry period; 3) the Atlantic period (c.5800BCE-4000BCE) which was warm and wet; and 4) the Subboreal (c.4000BCE-2500BCE) when it was drier and cooler than the Atlantic, but still warmer than today. There is a further subdivision, the Subatlantic , which started around 2500BCE and is ongoing today. It is slightly cooler than the Subboreal and Atlantic periods. The ice age steppe (grassland) animals such as mammoth either died out or moved away as woodlands grew over huge parts of the country.  , such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats., such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats., such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats. , although given the propensity of modern day humans to hunt endangered species to extinction, human interference should not be ruled out. Forests grew further north than they do now and the Sahara was green and supported considerable life. New species of animal, such as deer, horses, aurochs, wild pig, otter and beaver, followed the trees. This is the time when Britain began to be repopulated and Cunliffe says ‘these pioneers were the direct ancestors of the majority of the people living in the islands today’.

, such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats., such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats., such as woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats. , although given the propensity of modern day humans to hunt endangered species to extinction, human interference should not be ruled out. Forests grew further north than they do now and the Sahara was green and supported considerable life. New species of animal, such as deer, horses, aurochs, wild pig, otter and beaver, followed the trees. This is the time when Britain began to be repopulated and Cunliffe says ‘these pioneers were the direct ancestors of the majority of the people living in the islands today’.

Things to think about

- How much of an impact are humans having on the Earth and its climate? How much impact can humans make?

- Is the Anthropocene a valid epoch?

- What does an understanding of ice ages do to our understanding of the modern environment?

- How would changes in temperature affect the people, animals and plants living in Britain?

- How and when do you think Britain became an island again?

Things to do

- Study the weather records that are available online to tell your own story about recent changes in climate. Can you make weather predictions for the next hundred years?

- Would your home town have been under ice (or water)? Look at maps of previous glacial maximums and ancient rivers to decide.

- Visit your local museum. Often local museums carry the fossils of ancient animals living in the local area; perhaps you will see hippo or monkey bones.

Further reading

A brief and easy read on the history of the climate and its study is Jamie Woodward's The Ice Age: A Very Short Introduction (part of OUP's Very Short Introductions range). Chris Stringer covers climate - among many other Stone Age questions - in his book (which is somewhat outdated) Homo Britannicus: The Incredible Story of Human Life in Britain.