Key facts about Napoleon

- Napoleon was a French general and leader

- He became first consul in 1799 after a coup

- He named himself emperor in 1804

- Napoleon invaded, and lost, much of Europe during the Napoleonic Wars

- He oversaw a number of changes in society and in the law

- Few historians can agree on whether he was a force for good, or for bad

- He was eventually exiled on the South Atlantic island of St Helena

People you need to know

- Alexander I - Russia tsar from 1801 until 1825.

- Napoleon Bonaparte - a French military and political leader who gained power during the French Revolution and became French emperor.

- Neil Campbell - a British gentleman and general during the Napoleonic Wars.

- Frederick Maitland - Royal Navy officer during the Napoleonic Wars and captain of HMS Bellerophon.

- Marshal Ney - French military commander, known by Napoleon as 'the bravest of the brave' during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

- Maximilien Robespierre - a leading French lawyer and politician during the Revolution, until his arrest and execution in 1794.

In Britain, Napoleon is seen as a villain, mainly remembered for overthrowing the government and for war. His reputation is such that a (disproven) neurosis is named after him – the ‘Napoleon complex’, which suggests all those of limited height act in an aggressive manner to compensate.  This, and much else that we think we know of Napoleon, has no – or very little – basis in reality, but has instead come from effective British propaganda against him.

This, and much else that we think we know of Napoleon, has no – or very little – basis in reality, but has instead come from effective British propaganda against him.

The British establishment liked neither the French Revolution nor Napoleon.  Despite Britain not having an absolute monarchy , there was much to concern the upper classes about events in France, particularly once the Terror began. Too much had changed in the last century in British society and in the economy; there had been too much movement of people, both socially (with power transferring from those with land to those with money, often made through the agrarian and industrial revolutions) and geographically (as those working on the land moved to the cities, a hotbed of dissent ). Fundamental aspects of belief were changing and being questioned; and Britain had just lost America to revolutionaries, making her feel more insecure. The British establishment worried it would be next. It was in their interests not just to fight the French, but to win the hearts and minds of those at home.

Despite Britain not having an absolute monarchy , there was much to concern the upper classes about events in France, particularly once the Terror began. Too much had changed in the last century in British society and in the economy; there had been too much movement of people, both socially (with power transferring from those with land to those with money, often made through the agrarian and industrial revolutions) and geographically (as those working on the land moved to the cities, a hotbed of dissent ). Fundamental aspects of belief were changing and being questioned; and Britain had just lost America to revolutionaries, making her feel more insecure. The British establishment worried it would be next. It was in their interests not just to fight the French, but to win the hearts and minds of those at home.

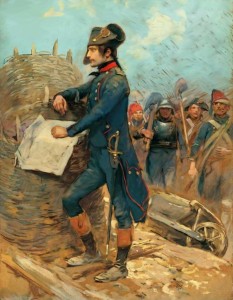

Napoleon's life and career

Napoleon Bonaparte was born to minor Corsican nobility in 1769.  Enrolled in school in France, he was considered socially and financially inferior by his peers who teased him for his accent. Nevertheless, he gained admittance to the prestigious and very expensive École Militaire in Paris at 15, shortly before the loss of his father to stomach cancer. With the family’s only source of income gone, Napoleon was forced to complete the two year course in just one. He graduated 42nd out of 58, becoming a commissioned officer just after his 16th birthday, and went on to serve in the French Revolutionary Wars.

Enrolled in school in France, he was considered socially and financially inferior by his peers who teased him for his accent. Nevertheless, he gained admittance to the prestigious and very expensive École Militaire in Paris at 15, shortly before the loss of his father to stomach cancer. With the family’s only source of income gone, Napoleon was forced to complete the two year course in just one. He graduated 42nd out of 58, becoming a commissioned officer just after his 16th birthday, and went on to serve in the French Revolutionary Wars.

He first came to the attention of Paris as an artillery lieutenant by capturing the naval fort of Toulon in 1793 after a royalist uprising supported by the British navy. Following Toulon he was earmarked for promotion and in 1797, he succeeded in driving the Austrians out of Italy (despite them having the much larger force).

Only two years later, Napoleon led a coup against the Directory , the ruling committee of five established in 1795 shortly after the fall of Robespierre. The Directory had overseen a number of French defeats and Napoleon, naming himself first consul, effectively established a military dictatorship. He reorganised the army and went on to win a series of victories, in what became known as the Napoleonic Wars.  The Second Coalition of countries against France collapsed, leaving Britain to fight alone and eventually to sign the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. This treaty lasted only a year amid further moves by Napoleon to expand France's territories.

The Second Coalition of countries against France collapsed, leaving Britain to fight alone and eventually to sign the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. This treaty lasted only a year amid further moves by Napoleon to expand France's territories.

By 1808, the Emperor Napoleon (he had declared himself Emperor in 1804) had conquered much of Europe, but started making serious military mistakes. In 1808, he placed his elder brother, Joseph, on the Spanish throne, starting the expensive Peninsular War; and in 1812 he invaded, and was defeated by, Russia. By March 1814, the allies of the Sixth Coalition had reached Paris. The leaders of Paris surrendered, Napoleon was forced to abdicate on 1 April 1814 and was retired to Elba. However in February 1815 he escaped, thanks to the foresight of the Russians in placing him so close to France, the gossiping nature of Napoleon’s British guests and the carelessness of his guard, Sir Neil Campbell.

Following Napoleon’s escape, he marched on Paris where many sent against him supported him: the French general sent to capture Napoleon, Marshal Ney, switched sides as did a number of prisoners of war and other seasoned soldiers. But at Waterloo, Napoleon was defeated and fled the battlefield. He made his way to Rochefort, probably hoping to find safe passage to America, which had supported the French during the Wars. Finding all ports blockaded by the British, he was left with little choice but to claim asylum. On 15 July 1815, almost a month after his defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon turned himself over to Captain Frederick Maitland, commander of HMS Bellerophon.

He died six years later, miserable and illegally exiled by the British on the island of St Helena.  The official cause of death was stomach cancer, although many conspiracy theories surround it, mainly because his symptoms suggest arsenic poisoning. Some think it was the British state quietly killing their enemy, although analysis of his hair throughout his life shows he had always been exposed to high levels of arsenic.

The official cause of death was stomach cancer, although many conspiracy theories surround it, mainly because his symptoms suggest arsenic poisoning. Some think it was the British state quietly killing their enemy, although analysis of his hair throughout his life shows he had always been exposed to high levels of arsenic.

Napoleon's character and legacy

Napoleon's character is difficult to pin down. He was full of contradictions and seemed to change according to the person, the circumstance and his mood. Some historians, such as Geoffrey Ellis and R.S. Alexander, have seen this as the basis for his popularity, allowing others to see in him what they wanted. His goal was not to please humanity, but to find something to make his critics respond to him as either a lawmaker, warrior or saviour. This ability to adapt could be why there is still so little agreement over him today. Whatever else though, he was considered intelligent, proven by his ability to dictate four different letters to four different secretaries on four different subjects at a time. While sometimes being likened to a volcano because of his temper, he could also be charismatic and likeable. In addition to convincing a number of people to turn traitor, he charmed the gaoler on the ship taking him into exile in 1814,  and a stream of English guests who visited him on Elba.

and a stream of English guests who visited him on Elba.

There is no doubt Napoleon had a dark side. He copied the ancien régime , living in luxury and promoting friends and relatives to positions of power.  regime in the Soviet Union proved Orwell's point that 'some animals are more equal than others'. In Spain he invaded and toppled the old regime, placing his brother, Joseph, on the throne, prompting the Peninsular War. Perhaps he wanted to bring liberté, égalité, fraternité to the rest of Europe, but Napoleon didn't just fight against monarchies: he inflicted regime change on several ancient republican city states, such as Venice and Dubrovnik. His wars killed over a million people from his own country, and perhaps double that from other European nations. He could be absolutely brutal, abandoning entire armies, like in Egypt, when strategy required.

regime in the Soviet Union proved Orwell's point that 'some animals are more equal than others'. In Spain he invaded and toppled the old regime, placing his brother, Joseph, on the throne, prompting the Peninsular War. Perhaps he wanted to bring liberté, égalité, fraternité to the rest of Europe, but Napoleon didn't just fight against monarchies: he inflicted regime change on several ancient republican city states, such as Venice and Dubrovnik. His wars killed over a million people from his own country, and perhaps double that from other European nations. He could be absolutely brutal, abandoning entire armies, like in Egypt, when strategy required.  Nor was he always successful in war: he was totally defeated (and forced to abdicate) twice. His wars against the Holy Roman Empire resulted in 'arguably the most damaging own goal in European history'

Nor was he always successful in war: he was totally defeated (and forced to abdicate) twice. His wars against the Holy Roman Empire resulted in 'arguably the most damaging own goal in European history'  by reunifying Germany, which led to the invasions of France in 1870, 1914 and 1940. Nor can it be denied that he gave Britain what she needed: the moral upper hand. The coup d’état provided the moral justification to continue fighting, as the British were no longer standing against an emerging democracy, but against a tyrant. He had turned from liberator to oppressor.

by reunifying Germany, which led to the invasions of France in 1870, 1914 and 1940. Nor can it be denied that he gave Britain what she needed: the moral upper hand. The coup d’état provided the moral justification to continue fighting, as the British were no longer standing against an emerging democracy, but against a tyrant. He had turned from liberator to oppressor.

However, on the Continent and particularly in France, memories are much more forgiving. Some of this is reaction against the political order that emerged after his exile, where his faults were forgotten but his great acts remembered fondly. It was also a result of his own propaganda machine. Even after his defeat at Waterloo, he was still concerned with image, leading him to dictate memoirs which, to a large extent, have affected how he has been viewed by history. Through exaggeration, self-promotion, and censorship he built a cult of personality around himself. His reputation as a military genius was at least in part deserved. While some would argue he didn't change tactics at all between 1800 and 1815 - suggesting he didn't have the necessary flexibility to be a competent general - others have pointed to his reorganisation of the army which changed the scale of warfare across Europe. He was quick to publicise his military successes, no matter how small: a skirmish over a bridge at Lodi in modern Italy was turned within three days into a major triumph. But he was also a successful military leader, winning almost all of his 50 pitched battles .  Some historians have gone so far as to say 'it is doubtful that the legend does the man justice'.

Some historians have gone so far as to say 'it is doubtful that the legend does the man justice'.

But he was remembered for more than military success, and by his contemporaries he was perhaps thought of as a politician first. As Harvey puts it, he was seen 'not as a general who became a dictator but as a dictator who was also a general.'  He portrayed himself as the strong man who could bring peace and security to his country following the terrible years of the Revolution. He promised a return to order and a reduction in crime. This he did by shaping the two police forces he inherited, turning them into models for much of Europe during the 19th century.

He portrayed himself as the strong man who could bring peace and security to his country following the terrible years of the Revolution. He promised a return to order and a reduction in crime. This he did by shaping the two police forces he inherited, turning them into models for much of Europe during the 19th century.  Rather than simply invading and destroying, he could be a progressive moderniser and boasted about preserving the achievements of the Revolution. In 1804 he introduced the Code Napoleon, or the Code civil des Français, across the conquered territories,

Rather than simply invading and destroying, he could be a progressive moderniser and boasted about preserving the achievements of the Revolution. In 1804 he introduced the Code Napoleon, or the Code civil des Français, across the conquered territories,  which is still the core of civil code today.

which is still the core of civil code today.  This code included three main principles: clarity, so that all could understand the law, rather than relying on experts; secularism; and the right to ownership of property and employment free from servile obligations. This code modernised law, and thereby society itself. Despite his own tendencies towards despotism, he is remembered as having liberated Europe from the tyrannies of the church and religious oppression.

This code included three main principles: clarity, so that all could understand the law, rather than relying on experts; secularism; and the right to ownership of property and employment free from servile obligations. This code modernised law, and thereby society itself. Despite his own tendencies towards despotism, he is remembered as having liberated Europe from the tyrannies of the church and religious oppression.

Napoleon had a vision for Europe and he succeeded in making that vision a reality, at least for a while. Whether he was a saviour of the people or a war-mad megalomaniac might simply be down to the loudest propaganda. Whatever else, he was an enigma, and someone who will continue to fascinate, inspire and disgust down the generations.

Things to think about

- How much has British propaganda affected our opinion of Napoleon?

- How did Napoleon die?

- How would you describe Napoleon's character?

- What good did Napoleon do?

- Was Napoleon a good general?

- On balance, was Napoleon a force for good, or for bad?

Things to do

- There are a number of places associated with Napoleon dotted round Europe, if you've got the time and money to visit them. These include the Musée de l’Armée Invalides in Paris, where you can see Napoleon's final resting place (information can be found here); the Villa dei Mulini on Elba, where Napoleon was exiled and which is now a museum (information can be found here); and the museum of his birthplace (information can be found here).

- For those wanting to stay on this side of the Channel, it is possible to find out what life was like in Britain during the Napoleonic Wars by visiting, for example, HMS Victory at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. Our review can be found here and you can purchase tickets here.

Further reading

There are a number of biographies on Napoleon, varying in quality. Two of the best are Vincent Cronin's Napoleon and Alan Forrest's Napoleon. For information about the British response to Napoleon, a very good book is Roger Knight's Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793-1815.