Key points about Edward the Confessor

- Edward the Confessor was king of England between 1042 and 1066.

- He was thought of as very religious and later became a saint.

- He's considered a weak king.

- He died childless, creating a succession crisis that led to William of Normandy's invasion.

People you need to know

- Æthelred the Unready – king of England from 978-1016.

- Alfred – younger brother of Edward the Confessor.

- Cnut – king of England from 1017 to 1035, king of Denmark and son of Sweyn Forkbeard.

- Edith of Wessex – wife of Edward the Confessor, daughter of Earl Godwin and sister of Harold Godwinsson

- Edmund Ironside – son of Æthelred the Unready and his first wife, Ælfgifu of York. King in 1016.

- Edward the Confessor – son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy.

- Edward the Exile – son of Edmund Ironside.

- Emma of Normandy – daughter of the Richard I of Normandy. She became Æthelred’s second wife, and later became the second wife of Cnut.

- Earl Godwin of Wessex – a great Anglo-Saxon lord. Supporter of Cnut and father of Edward the Confessor’s wife.

- Harold Godwinsson - son of Earl Godwin and king of England in 1066.

- Harold Harefoot – son of Cnut by his first marriage to Ælfgifu of Northampton. King of England between 1035 and 1040.

- Harthacnut – son of Cnut and Emma of Normandy. King of England between 1040 and 1042.

- Sweyn Forkbeard – king of Denmark and father of Cnut.

- William of Normandy – born outside of wedlock, great-grandson of Richard I of Normandy (and Emma of Normandy’s great-nephew); later to become the Conqueror.

Edward the Confessor, thought of as the penultimate Anglo-Saxon king,  died childless on 5 January 1066, sparking the chain of events that led to the invasion of William of Normandy in September 1066.

died childless on 5 January 1066, sparking the chain of events that led to the invasion of William of Normandy in September 1066.  As the name implies, he is remembered as exceptionally pious, and was responsible for commissioning the building of Westminster Abbey. But he has gone down in history as having none of the qualities considered necessary for being a good medieval king.

As the name implies, he is remembered as exceptionally pious, and was responsible for commissioning the building of Westminster Abbey. But he has gone down in history as having none of the qualities considered necessary for being a good medieval king.

Edward the Confessor’s Exile and Return

Edward was born to Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy somewhere between 1003 and 1005. England was not particularly stable, or safe, during the first years of the eleventh century. Viking raiders repeatedly threatened the English coastline and were paid off with Danegeld, until, in 1013, the Danish king Sweyn and his son Cnut invaded England. The royal family fled to Normandy, where Edward almost constantly remained for 28 years, until his return in 1041.

In the meantime, and despite a valiant effort against the invaders by Edmund Ironside, Cnut became sole king in 1016. The success and stability - particularly for the English - of Cnut's reign is up for debate, with some historians believing Cnut to have been a largely peaceful and benevolent king, based mainly on the evidence of some heavily biased texts and the silence of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Others, however, point not only to the culture clash intrinsic to such a conquest but also to Cnut's brutality in dealing with 'suspicious' English, to suggest that the reign was not one of complete harmony. There was one Englishman, though, who did well under Cnut: Godwin. By the 1030s, he had risen from unknown, and therefore reasonably humble, origins to become earl of Wessex and Cnut's right-hand man, and he was therefore in something of a quandary when Cnut died with no obvious successor in 1035. Cnut had left two main contenders: Harold Harefoot, his son by his first wife, and Harthacnut, his son by his second wife - and mother of Edward - Emma of Normandy. The problem was that, in 1035, Harthacnut was not in England. The Witangemot therefore decided that Harold should rule as regent, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated., because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated. over the whole kingdom until Harthacnut's return (the exception being Wessex, which would be ruled over by Emma as representative of her son), at which point a more permanent solution would be found. But Harthacnut did not return that year, strengthening Harold's position to the detriment of Emma and her son.

In the meantime, and despite a valiant effort against the invaders by Edmund Ironside, Cnut became sole king in 1016. The success and stability - particularly for the English - of Cnut's reign is up for debate, with some historians believing Cnut to have been a largely peaceful and benevolent king, based mainly on the evidence of some heavily biased texts and the silence of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Others, however, point not only to the culture clash intrinsic to such a conquest but also to Cnut's brutality in dealing with 'suspicious' English, to suggest that the reign was not one of complete harmony. There was one Englishman, though, who did well under Cnut: Godwin. By the 1030s, he had risen from unknown, and therefore reasonably humble, origins to become earl of Wessex and Cnut's right-hand man, and he was therefore in something of a quandary when Cnut died with no obvious successor in 1035. Cnut had left two main contenders: Harold Harefoot, his son by his first wife, and Harthacnut, his son by his second wife - and mother of Edward - Emma of Normandy. The problem was that, in 1035, Harthacnut was not in England. The Witangemot therefore decided that Harold should rule as regent, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated., because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated. over the whole kingdom until Harthacnut's return (the exception being Wessex, which would be ruled over by Emma as representative of her son), at which point a more permanent solution would be found. But Harthacnut did not return that year, strengthening Harold's position to the detriment of Emma and her son.

By 1036, she was desperate enough to recall her sons by her first marriage, either hoping they would fight in support of Harthacnut or that they would claim the crown for themselves, thus protecting Emma's position as 'first lady' of England. Edward landed at Southampton with 40 ships, but was met by a large army of Harold's supporters. Although William of Jumièges records that he won the ensuing battle, he decided not to risk going further into England, and returned to Normandy. Alfred, who probably travelled later and maybe in response to his brother's failure, was met by Earl Godwin and he and his men were taken to Guildford where they enjoyed a feast. However, later that night Godwin's men attacked them. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 'some of them were sold for money, some cruelly destroyed; some of them were fettered, some of them were blinded; some maimed, some scalped.' Alfred was likewise blinded and left in the care of the monks of Ely, where he died of his wounds shortly afterwards. It was a brutal and dishonest act, which the Chronicle considered to be the worst atrocity in 20 years, but it was also an act of desperation by Godwin: Edward and Alfred would not look favourably on a man who had profited so much from their previous downfall and exile. Following the death of Alfred, Emma spread the rumour that the invitation to her sons, and her seal, had been forged as a trap. She held out in Wessex for another year, before seeking refuge on the Continent. It is telling, however, that she did not go to Edward, but stayed in Bruges, where she could be more helpful to Harthacnut.

When Harold died in 1040 and Harthacnut eventually came to claim his inheritance, Edward was invited back to court. It is possible that the two half-brothers, together with their mother, ruled the kingdom jointly. But just a year later, while drinking at a wedding feast, Harthacnut ‘suddenly fell to the earth with an awful convulsion, and…passed away.’  No-one knows the cause of death, although poisoning is an obvious suspect. Some, however, point to a long line of sudden deaths in the Norman line and wonder whether there was an unnamed congenital disease affecting it.

No-one knows the cause of death, although poisoning is an obvious suspect. Some, however, point to a long line of sudden deaths in the Norman line and wonder whether there was an unnamed congenital disease affecting it.  Although Edward had achieved the crown with his mother’s help, he had her arrested, banished from court, and her treasure confiscated.

Although Edward had achieved the crown with his mother’s help, he had her arrested, banished from court, and her treasure confiscated.  Edward was now sole ruler of England.

Edward was now sole ruler of England.

Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Two factions quickly emerged in England during Edward the Confessor's reign. Edward, raised in Normandy and with Norman blood through his mother, surrounded himself with Norman advisers and looked to introduce a cultural revolution in England. A few castles, completely unknown to England before Edward, were built in the Welsh Marches and in Essex, and the first signs of a church reform movement, already underway in France, appeared with the building of the Romanesque Westminster Abbey and the appointment of foreign bishops.  It is little wonder that he preferred trusted advisers whom he had known for years and who shared similar tastes and experiences, over Anglo-Saxon lords with whom he had little in common. But it may be that it wasn’t just cultural preference informing these decisions: perhaps Edward was still wary of the man who had caused the death of his brother.

It is little wonder that he preferred trusted advisers whom he had known for years and who shared similar tastes and experiences, over Anglo-Saxon lords with whom he had little in common. But it may be that it wasn’t just cultural preference informing these decisions: perhaps Edward was still wary of the man who had caused the death of his brother.

Regardless of the reasons, many Anglo-Saxons were excluded from power and so rallied round the immensely wealthy Earl Godwin. Surprisingly, Godwin had survived the accession of Edward thanks to an alliance of convenience between the two: Edward was friendless and Godwin, for all his wealth - with personal lands stretching from Cornwall to Kent - was crownless. The uneasy pact should, in theory, have been strengthened by the marriage between Edward and Godwin's daughter, the beautiful Edith, providing the one with connections and the other with a grandchild on the throne. But the relationship that had started out as awkward at best quickly worsened, and Godwin thus made a good figurehead for the disaffected Anglo-Saxons at court.

Regardless of the reasons, many Anglo-Saxons were excluded from power and so rallied round the immensely wealthy Earl Godwin. Surprisingly, Godwin had survived the accession of Edward thanks to an alliance of convenience between the two: Edward was friendless and Godwin, for all his wealth - with personal lands stretching from Cornwall to Kent - was crownless. The uneasy pact should, in theory, have been strengthened by the marriage between Edward and Godwin's daughter, the beautiful Edith, providing the one with connections and the other with a grandchild on the throne. But the relationship that had started out as awkward at best quickly worsened, and Godwin thus made a good figurehead for the disaffected Anglo-Saxons at court.

The crisis came in 1051, when a fight broke out in Dover between the followers of Edward's French brother-in-law and the townsfolk. Godwin, whose land included Dover, was ordered to punish the town but refused. Battle between Edward and Godwin nearly ensued but the two sides, unwilling to sacrifice many of England's best men and leave the way open to foreign enemies, agreed to negotiate. It did not go well for Godwin and his family, who fled into exile after hearing Edward's terms: they could have peace as soon as Godwin was able to restore Edward's brother Alfred. However, it wasn’t long before the Godwin family returned complete with raiding parties and gained an increasing number of followers. Again the two side were forced to negotiate, but this time Godwin had the upper hand. The family was reinstated in their lands, titles and wealth, and Edward's Norman supporters - including the Archbishop of Canterbury Robert of Jumièges - were forced to flee. With Edward's support significantly reduced, there was nothing to prevent Godwin claiming even more power and from 1052 Earl Godwin became the de facto  ruler. Even when Godwin died suddenly in 1053, Edward was not free: his sons Tostig and Harold Godwinsson took the reins.

ruler. Even when Godwin died suddenly in 1053, Edward was not free: his sons Tostig and Harold Godwinsson took the reins.

Marriage

Whatever his personal feelings towards the Godwin family, Edward felt – or was – obliged to marry Godwin’s daughter, Edith. Edith was considered to be one of the most beautiful women in England, yet the couple never had children, and it has sometimes been assumed that he was too spiritually preoccupied to consider matters of the flesh. In the petitions for Edward’s canonisation, it was stressed that he had remained a virgin all his life, and perhaps he had made a vow of chastity. Or, as R. Allen Brown suggests, it was a loveless and distant match that was most beneficial to Godwin. Some have even suggested that Edward’s vow of celibacy was taken to frustrate Earl Godwin. Tom Holland has said that neither of these explanations are sufficient. It would seem that Edward had grown dependent on his wife’s advice in everything from fashion to affairs of state. This is hardly an indication of a loveless marriage, or one lacking in respect. Perhaps, then, one or other of them was infertile or maybe, as some contemporaries claimed, it was a punishment for their sins. Whatever the cause, the couple did not produce children. Although succession wasn't based purely on primogeniture, as was supposedly the case after the Norman conquest, the lack of an obvious successor - which a legitimate child would have been - led directly to invasion by William.

Crisis of Succession

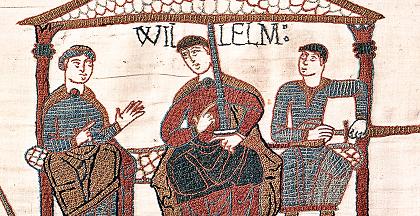

So who did Edward the Confessor name as his successor? The Bayeux Tapestry says that he had named William of Normandy, although no-one can precisely date when this might have happened. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that William visited in 1051, perhaps to be named successor or maybe to request help with his own wars with Anjou. But these very wars would have made a trip to England unlikely. Some Norman sources suggest that an embassy was later sent from Edward to William, but it is difficult to find when this might have taken place. Then there is the difficult question of how Harold Godwinsson washed up on the shores of Normandy after a shipwreck. Why was he going to Normandy in the first place (if that was the reason for his voyage) if not to discuss the succession? The Norman literature certainly makes the case that William was Edward's chosen heir, and that Harold supported this choice. However, situations can change. Harold Godwinsson certainly seemed to be the legitimate successor after Edward's death. Edward allegedly named him so on his deathbed, and the Witangemot confirmed the choice. True, he did not have royal blood, but he was powerful and had effectively been running the kingdom during the latter part of Edward's reign. Furthermore, he wasn't Norman. He was though, at least in Norman propaganda , an oath breaker, who had promised after his shipwreck to support William's claim to the throne.

It seems as though Edward had tried to avoid the inevitable Norman/Anglo-Saxon conflict by making plans to pass the succession to his exiled nephew (son of his half-brother Edmund Ironside) Edward the Exile, or Ætheling (meaning 'prince'). Just babies when their father was killed, Edward the Exile and Edmund Ætheling were sent to the king of Sweden with a letter of death – similar to that sent with Hamlet in Shakespeare’s play. Their execution never happened and Edward grew up in exile, until in 1054 he was invited to return to England by Edward the Confessor as the heir apparent . It took over two years for him to reach England, which he did in 1057. Although we don’t know how and by whom, he was prevented from meeting the king – thus confirming the succession – and within 48 hours of his return, he was suddenly dead. Although William of Normandy would certainly have had motive for the murder, he did not have the opportunity. The only faction powerful enough to have motive and opportunity, was that of the future king of England, Harold Godwinsson.

The Cult of Edward the Confessor and Canonisation

Edward the Confessor died on 5 January 1066, apparently prophesying that ‘devils shall come through this land with fire, sword and war’. He had suffered a number of strokes in the preceding year, weakening him to the point that, by Christmas 1065, he was mortally ill. Reports of miraculous cures at his tomb began soon after his burial, and in 1102 his tomb was reopened and his body was said not to have decayed (a sign of godliness). In the 1120s William of Malmesbury wrote of miracles he was meant to have performed during his life, including a blind man being given his sight. Osbert of Clare, prior of Westminster in the 1130s, wrote of him having cured scrofula could cure it by touching the afflicted person. The belief was common throughout the Middle Ages and lasted until the Enlightenment. could cure it by touching the afflicted person. The belief was common throughout the Middle Ages and lasted until the Enlightenment. could cure it by touching the afflicted person. The belief was common throughout the Middle Ages and lasted until the Enlightenment. , the 'King's Evil' by his touch, a tradition which lasted until George I. From the late 1130s onwards, with the English re-establishing their identity, the pope was petitioned by the English, including Henry II, to canonise Edward. In 1161, the Church agreed, naming him the patron saint of difficult marriages.

A weak king?

So why was Edward seen as a weak king? Undoubtedly, some of it is due to the crisis that followed his death. If he had produced offspring, then perhaps William would never have come a-conquering. The cult of Edward the Confessor, and his canonisation in 1161 has given him the aura of a deeply spiritual man, too preoccupied with religion to do much else. could be seen as a manifestation of earthly power (but not always ‘greatness’). In a monotheistic culture, the next best thing to becoming a god would be becoming a saint. But the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle portrays him as a strong king rather than a saint. Certainly during his reign, England had remained peaceful, without the major upheavals experienced throughout the first half of the eleventh century. As Holland says ‘Prosperity had returned to the kingdom: its trade had swelled, its wealth had grown, its towns had boomed.’ By any normal measure, this would be judged as a success.

Things to think about

- What was Emma of Normandy's role in Alfred's death?

- What caused Harthacnut's death?

- Was there a hereditary illness in the House of Normandy?

- What was Edward's relationship with Earl Godwin?

- Why didn't Edward and Edith have children?

- How did Edward the Exile die?

- How religious was Edward?

- Was Edward a weak king?

Things to do

- Visit Westminster Abbey to see Edward the Confessor's shrine. Edward the Confessor rebuilt St Peter's Abbey, upon which the current Westminster Abbey is built. Find out more about visiting Westminster Abbey here.

Further reading

Sadly, there are few good books on Edward the Confessor, who tends to be overlooked in the history of England. Still the best resource, which was first published in 1970, is Frank Barlow's Edward the Confessor.