Key facts about Operation Barbarossa

- Operation Barbarossa was the codename for the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union

- The invading force was the biggest in history

- The Germans had hoped for a quick success

- They failed because the Soviet Union had so much manpower, a cold winter climate and was so big

- Hitler split the invading force, making success less likely

- Operation Barbarossa might be the reason the Nazis lost the war

People you need to know

- Adolf Hitler - leader of the Nazi Party and Führer of Germany.

- Josef Stalin - leader of the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s until his death in 1953.

On 22 June 1941 the Nazis launched Operation Barbarossa, the biggest invasion force in the history of warfare against their ally , the Soviet Union.

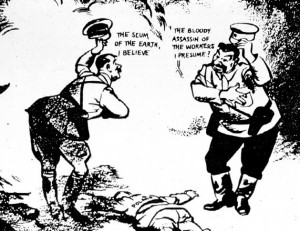

In August 1939, Hitler and Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, protecting them from direct and indirect attack from each other, as well as secretly dividing the whole of Eastern Europe between them. While it had been designed to last ten years, with an automatic extension of a further five years (unless it was cancelled with a year’s notice), in fact it lasted less than two. With Hitler’s forces having conquered western continental Europe, but being held at bay by the British, Hitler turned his attention impatiently to his main ideological goal: destroying the communist (and therefore Jewish) threat and finding Lebensraum for ethnic Germans. Initial plans were in preparation from as early as May 1940, but were changed in December that year. The new plan had three main foci: securing the Balkans and Leningrad to the north, the Ukrainian bread basket to the south, and Moscow in the centre. Hitler saw all three of these three areas as essential, but came under criticism, then and after, for splitting his forces.

The invasion date was planned for 15 May 1941, which would have given Hitler the summer season to conquer Russia, but was delayed due to troops being diverted to the Balkans and an exceptionally wet winter, which kept flood levels higher than would normally have been expected. When Operation Barbarossa did begin, more than a month late, the invasion involved over 3 million Axis troops (including those from Finland and Romania), using 3,350 tanks, 7,200 artillery pieces, 600,000 vehicles and 625,000 horses, as well as 65% of the Luftwaffe (2,770 aircraft). 75% of the German army would go on to serve in the Soviet Union at some point. These figures made it the biggest invasion force to date and surprised Stalin, who had been unwilling to believe the mounting evidence that Hitler would break the Pact so quickly.

Unsurprisingly, the Nazis made good initial gains. Some units advanced 50 miles in one day and with Stalin forbidding his generals to retreat – even tactically – thousands of Soviet soldiers were encircled and defeated: 250,000 were lost around Minsk at the end of June; 180,000 were taken prisoner at Smolensk; and there were 500,000 Soviet casualties at the Battle of Kiev in September.

Even with these impressive victories, the Germans, reliant mainly on their tanks, were struggling with their own losses.  As the year wore on bad decisions from Hitler, as well as worsening weather, slowed the invasion. Having been used to the successes of Blitzkrieg in the west, the Germans were expecting a quick win and had not prepared for the winter cold. Despite this, and with supply lines stretched to their limit, the Germans continued to press for Moscow, the outskirts of which they reached in early December. Even with heavy Soviet losses, the Russians had such massive reserves of manpower that they successfully defended and launched a counterattack, pushing the Germans back in a manner similar to Napoleon’s troops in 1812.

As the year wore on bad decisions from Hitler, as well as worsening weather, slowed the invasion. Having been used to the successes of Blitzkrieg in the west, the Germans were expecting a quick win and had not prepared for the winter cold. Despite this, and with supply lines stretched to their limit, the Germans continued to press for Moscow, the outskirts of which they reached in early December. Even with heavy Soviet losses, the Russians had such massive reserves of manpower that they successfully defended and launched a counterattack, pushing the Germans back in a manner similar to Napoleon’s troops in 1812.  Eventually the German lines stabilised, but their attempt at Blitzkrieg had failed.

Eventually the German lines stabilised, but their attempt at Blitzkrieg had failed.

From now on the Nazis faced a bitter, brutal and drawn-out war in the east. Had they not been so driven ideologically, they may have been more successful. Instead of believing that the Soviet High Command was backward and inept, they could have given them their credit and prepared better. And instead of looking down on the ‘Slavic’ occupied nations they passed through, they could have made much better use of the manpower these nations offered: many of those they ‘liberated’ initially welcomed them as heroes, until the shootings began.

It has been argued, and quite successfully, that if the Germans had won the initial surge, the whole course of the war would have changed. Without having to fight on multiple fronts, they would have been more likely to win. The problem is that only a fool – or someone so blinded by ideology and snobbery that they became a fool – could ever have hoped to win against Russia in a land war. Napoleon had tried and failed under similar conditions, but the successes on the western front had made the Germans complacent. The key ‘what if’ then, shouldn't be ‘what would have happened if the Germans had won’, rather ‘what would have happened if they hadn't invaded’.

Things to think about

- What does the Nazi-Soviet Pact tell us about Hitler and Stalin?

- Was Operation Barbarossa doomed to fail from the start?

- What could have been done by the Germans to achieve victory?

- What would a German victory in the USSR have meant for the result of the Second World War?

- Would it ever be possible to win a land war against Russia?

Things to do

- What would you have done differently? Design a battle plan for a successful Operation Barbarossa.

Further reading

For an in-depth study of Operation Barbarossa, Robert Kershaw's War without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 is a good, if lengthy start. The best person to read to gain an understanding of Nazi Germany and Hitler is Ian Kershaw. He has written extensively on the Third Reich , but one (or two) of his best is the biography of Hitler that was first published in two parts and has now been abridged into one volume.