Elizabeth I is one of England’s most recognisable monarchs. Reigning for almost forty-five years she has come to represent a time of English peace and strength, where she walked the line between the Virgin Queen and the mother of the nation; between feminine ideal and successful statesman; between absolutism and parliamentarianism, religious reform and religious tradition. Her reign is remembered as a glorious golden age, when the English began to establish their place in the world, and when their culture flourished.

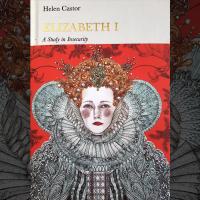

It is hardly surprising, then, that Elizabeth has attracted a huge number of biographies, written by some of the best-known names in the business: David Starkey, John Guy, Alison Weir, Susan Doran, and Patrick Collinson. What is perhaps more surprising is why it was felt another biography was needed. Elizabeth I: A Study in Insecurity by Helen Castor provides the answer. This small book, totalling just less than one hundred pages of text, is part of the Penguin Monarchs series, which aims to provide ‘short, fresh accounts of England’s rulers from Aethelstan to Elizabeth II’. Approachable, succinct, and well-written histories are the series’ goal, but almost by its very nature it limits the contribution to historical understanding that can be found in larger works. Castor's book, however, manages to do both. While keeping a flowing pace and engaging language, the author introduces a new perspective on Elizabeth, creating an argument at the outset that grows stronger throughout the book. This is a remarkable achievement.

Approachable, succinct, and well-written histories are the series’ goal, but almost by its very nature it limits the contribution to historical understanding that can be found in larger works. Castor's book, however, manages to do both. While keeping a flowing pace and engaging language, the author introduces a new perspective on Elizabeth, creating an argument at the outset that grows stronger throughout the book. This is a remarkable achievement.

Castor’s thesis is simple, despite its novelty: Elizabeth I was an intelligent yet insecure lady, who was deeply affected by her mother’s death at the hands of her father. Thrown unexpectedly into power – she survived both her brother and her elder sister’s reigns – she applied the lessons to statecraft that she had learnt as a child: that it was better to be circumspect than reckless, to find strength and security in inaction rather than in compulsive movement. Castor neatly sweeps aside arguments that lack of evidence implies lack of emotion over Anne Boleyn’s death, and impresses the reader with the danger inherent in Elizabeth’s position as the bastard child of a traitor, ‘when the toxic combination of the king’s monstrous ego and profound religious division made politics a bloodsport’.  Her inclusion of Elizabeth’s attempts at poetry, and her analysis of Elizabeth’s behaviour in surrounding herself with her mother’s blood relatives and wearing her mother’s portrait in a locket, while circumstantial, goes some way to filling that gap in the evidence. Furthermore, Castor turns Elizabeth’s dallying and delaying decisions – about marriage, about Mary Queen of Scots, about naming an heir – from a character flaw (and one that is often raised in biographies of the queen) into one of her greatest strengths. In this way, Castor engages with and refutes many of the historical opinions on Elizabeth’s reign, without ever becoming bogged down by historiography.

Her inclusion of Elizabeth’s attempts at poetry, and her analysis of Elizabeth’s behaviour in surrounding herself with her mother’s blood relatives and wearing her mother’s portrait in a locket, while circumstantial, goes some way to filling that gap in the evidence. Furthermore, Castor turns Elizabeth’s dallying and delaying decisions – about marriage, about Mary Queen of Scots, about naming an heir – from a character flaw (and one that is often raised in biographies of the queen) into one of her greatest strengths. In this way, Castor engages with and refutes many of the historical opinions on Elizabeth’s reign, without ever becoming bogged down by historiography.

A consequence of Castor’s approach is a more gender-orientated history of Elizabeth than is often found. Given Castor’s previous works, in particular the consideration given to powerful medieval women in She-Wolves, this is to be expected, yet it is a refreshing and eye-opening change that provokes a new understanding of Elizabeth’s position as queen. As Castor states, Elizabeth made choices – such as whether to risk her independence and security, as well as bodily harm, in the present to provide an heir for the future – that ‘no king had ever had to face’.  Furthermore, writes Castor, Elizabeth faced difficulties peculiar to a female head of state: the inability to lead an army into battle, so that her instructions were less likely to be obeyed; the ‘superiority’ of male councillors who couldn’t understand how ‘a mere woman might resist or reject their counsel’.

Furthermore, writes Castor, Elizabeth faced difficulties peculiar to a female head of state: the inability to lead an army into battle, so that her instructions were less likely to be obeyed; the ‘superiority’ of male councillors who couldn’t understand how ‘a mere woman might resist or reject their counsel’.  One could perhaps argue that the perspective is carried a little too far – medieval kings like Richard III risked their lives by leading armies into battle, for example, and Elizabeth was happy to play to her gender when it suited her – but her gender was an inescapable fact of her reign, and one that affected, for good or ill, how contemporaries saw her.

One could perhaps argue that the perspective is carried a little too far – medieval kings like Richard III risked their lives by leading armies into battle, for example, and Elizabeth was happy to play to her gender when it suited her – but her gender was an inescapable fact of her reign, and one that affected, for good or ill, how contemporaries saw her.

With a maximum word count of 25,000, there must always be brutal decisions made on what to include and what to exclude. Some reviewers have highlighted the need for more religious discussion, while similar arguments could be made for greater inclusion of the ‘rise’ of parliament. But this is not just a political biography; rather it is the complete-as-possible story of a monarch who was just as elusive to her contemporaries as she has been to many since. As such there is no need, nor any space, to labour points that are already covered. There is, perhaps, only one element lacking: the death of Elizabeth and the problems of succession are covered in just one page. Discussion of the confusion of Elizabeth’s final days would have illustrated the pitfalls of the queen’s approach: the art of ‘creating space by standing still’ and by continually changing her mind, by 1603, had become a threat to the country. This would, however, have provided a sour note on which to finish Elizabeth’s story, and it is easy to understand the appeal of a neater ending.

This would, however, have provided a sour note on which to finish Elizabeth’s story, and it is easy to understand the appeal of a neater ending.

This in no way should take away from the book. It is a pleasure to read: clear, concise, and eloquently and engagingly written. More than this, however, it raises new questions and new perspectives, backed up by the available evidence and by sound reasoning. Rarely have so few pages, printed as popular history, contributed so much to the historical understanding of a particular field. As such, this is no mere brief introduction; it is a story that needs to be read by every person interested in Tudor history.