Key points about the Norman Conquest

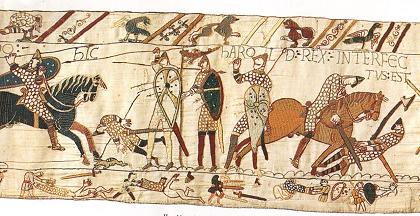

- The Normans, led by William I, invaded England in 1066.

- England went through a period of change after the Norman Conquest.

- The Anglo-Saxon nobility were replaced with a Norman aristocracy.

- Society changed at every level, and the trade in slaves was banned.

- Culture and language changed.

- Castles appeared and cathedrals were rebuilt in a Romanesque style.

People you need to know

- Edward the Confessor - King of England from 1042 until 1066, who died without an heir.

- Gregory VII - Church reformer who was pope between 1073 and 1085.

- Lanfranc - William I’s spiritual adviser, celebrated intellect, light of the reformist movement, friend of Pope Gregory VII, and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1070 until 1089.

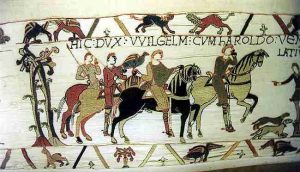

- Matilda of Flanders - wife of William I, and Queen of England.

- Stigand - Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury.

- William I - also known as 'the Conqueror'. Duke of Normandy, and King of England from 1066 until 1087.

- Wulfstan - Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, who was canonised in 1203.

Without doubt, the Norman Conquest had an impact on England, but recently historians have stressed its continuity, questioning whether the invasion can be viewed as a cataclysm. After all, any incident claiming the description must have far-reaching consequences for the organisation of the country, its government, laws and institutions, and its economy. It must also have a profound effect on people of every rank, on their culture and religion. There should be visual evidence of it, for example in architecture and land management. Furthermore, these changes must be directly traceable to the event, and must be ongoing. Does enough evidence exist to allow the claim to be made?

Law and administration

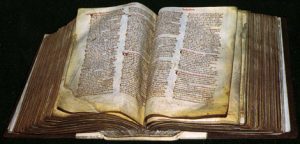

William's legitimacy as king was built on continuity. He invaded England not as some Viking looking for fresh pickings but as the rightful heir to Edward the Confessor. Any drastic change in administration or law would show the deceit in his claim. As such, the Anglo-Saxon organisation of government through hides, hundreds, and shires continued, and was essential for establishing Norman dominion: there would be no Domesday Book without it. Yet despite keeping the system in place – and why not, being fine-tuned for the collection of taxes – changes were made. Land was parcelled out to William's supporters differently, sometimes organised geographically, sometimes keeping the same boundaries as before, and sometimes combining the left-overs. Even when administration didn't change, those responsible for it did. The old Anglo-Saxon sheriffs were replaced by Normans, and Henry of Huntingdon recorded that 'Sheriffs and officials whose responsibility was justice and judgement were more frightful than thieves and robbers, and crueller than the most cruel.'

At his coronation , William swore 'that he would hold this nation as well as the best of any kings before him'.  He would continue the laws and practices of his predecessors, confirming, for example the status of London.

He would continue the laws and practices of his predecessors, confirming, for example the status of London.  But neither he, nor his underlings, kept the promise. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle complained that 'the greater the talk about just law, the more unlawful things were done. They levied unjust tolls and they did many other unjust things which are difficult to relate.'

But neither he, nor his underlings, kept the promise. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle complained that 'the greater the talk about just law, the more unlawful things were done. They levied unjust tolls and they did many other unjust things which are difficult to relate.'  Oderic Vitalis, looking to excuse the King, recorded that 'the English were groaning under the Norman yoke, and suffering oppressions from the proud lords who ignored the king's injunctions.'

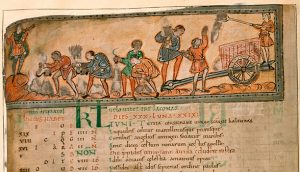

Oderic Vitalis, looking to excuse the King, recorded that 'the English were groaning under the Norman yoke, and suffering oppressions from the proud lords who ignored the king's injunctions.'  But William himself, an avid fan of hunting, established the royal forest and introduced forest law , which had a direct impact on those living in it. Although hunting land was set aside by the Anglo-Saxon nobility, it was nothing compared with what William instituted. John of Worcester lamented that 'on King William's command, men were expelled, homes were cast down, and the land was made habitable only for wild beasts.' Although Domesday shows much New Forest land was uncultivated in 1066, a further 15,000 to 20,000 acres were cleared, including 20 villages, a dozen hamlets and the 2,000 or so inhabitants.

But William himself, an avid fan of hunting, established the royal forest and introduced forest law , which had a direct impact on those living in it. Although hunting land was set aside by the Anglo-Saxon nobility, it was nothing compared with what William instituted. John of Worcester lamented that 'on King William's command, men were expelled, homes were cast down, and the land was made habitable only for wild beasts.' Although Domesday shows much New Forest land was uncultivated in 1066, a further 15,000 to 20,000 acres were cleared, including 20 villages, a dozen hamlets and the 2,000 or so inhabitants.  Livelihoods, and meal plans, were likewise destroyed, with heavy fines and punishments inflicted on those caught using the royal forests, for everything from chopping wood to hunting. The devastating impact of this could still be felt 300 years on, when its limitation was requested during the Great Revolt.

Livelihoods, and meal plans, were likewise destroyed, with heavy fines and punishments inflicted on those caught using the royal forests, for everything from chopping wood to hunting. The devastating impact of this could still be felt 300 years on, when its limitation was requested during the Great Revolt.

The economy

England's economy took a tumble immediately following the Conquest, but in the main it was short-lived, and the economy grew, perhaps more than it otherwise would, over the Norman period. However, the Economist recently blamed the current north-south economic divide on the Harrying of the North ,  and both Simeon of Durham and John of Worcester attest to the longevity of the devastation: the former that the villages and hamlets between Durham and York were uninhabited for nine years afterwards; the latter that even in the 1120s, much of the land was uncultivated. Upheavals were balanced with rewards. Thanks to the invasion, England developed closer ties with France, opening new trade routes and markets, but also bringing new problems. For the next several centuries, English people fought for their kings on foreign soil, and paid for it through high taxes. Closer ties with the Continent helped the economy to stabilise, but at the expense of trade with Scandinavia and, according to Hugh Thomas, the use and expertise of the navy.

and both Simeon of Durham and John of Worcester attest to the longevity of the devastation: the former that the villages and hamlets between Durham and York were uninhabited for nine years afterwards; the latter that even in the 1120s, much of the land was uncultivated. Upheavals were balanced with rewards. Thanks to the invasion, England developed closer ties with France, opening new trade routes and markets, but also bringing new problems. For the next several centuries, English people fought for their kings on foreign soil, and paid for it through high taxes. Closer ties with the Continent helped the economy to stabilise, but at the expense of trade with Scandinavia and, according to Hugh Thomas, the use and expertise of the navy.

Society

Arguably the greatest effect of the Norman Conquest was felt by the Anglo-Saxon nobility. At the start of William's reign, many Anglo-Saxons remained in positions of power, even witnessing Matilda's coronation. It seems unlikely that William set out to replace one aristocracy with another but by Domesday 'there was scarcely a noble of English descent in England, but all had been reduced to servitude and lamentation, and it was even disgraceful to be called English'.  Years of rebellion had taken their toll, and William's initial idea of a joint Norman and Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had proven unworkable. Those who had been present at Matilda's coronation in 1068 had, by 1086, been executed, murdered, imprisoned, exiled, or simply downgraded. Domesday records that of the thousand tenants-in-chief across England, thirteen were English and only four had lands worth more than £100.

Years of rebellion had taken their toll, and William's initial idea of a joint Norman and Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had proven unworkable. Those who had been present at Matilda's coronation in 1068 had, by 1086, been executed, murdered, imprisoned, exiled, or simply downgraded. Domesday records that of the thousand tenants-in-chief across England, thirteen were English and only four had lands worth more than £100.  Only 10% of their 8,000 subtenants were English. The result was a group of Norman super-rich, with half of English land held by just 200 Normans.

Only 10% of their 8,000 subtenants were English. The result was a group of Norman super-rich, with half of English land held by just 200 Normans.  Perhaps little has changed since: when the late Duke of Westminster was asked for the secret of his success, he replied 'Make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend of William the Conqueror.'

Perhaps little has changed since: when the late Duke of Westminster was asked for the secret of his success, he replied 'Make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend of William the Conqueror.'

The effects of the Conquest were not limited to the aristocracy, and considerable changes were experienced by the lower levels of society. Slavery was big business in Anglo-Saxon England, with slaves accounting for between 10% and 30% of the population, but not by 1066 in Normandy. As Conqueror, William issued a ban on the export of slaves and, while not immediately or wholly effective, its impact is evident in Domesday Book: their number in places such as Essex reduced by 25% between 1066 and 1086.  Perhaps, as already experienced in Normandy, there was a general trend – fuelled by economics – against slavery, although the Godwins, the most powerful pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon family, at least did not seem to notice.

Perhaps, as already experienced in Normandy, there was a general trend – fuelled by economics – against slavery, although the Godwins, the most powerful pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon family, at least did not seem to notice.  While slavery reduced, many more peasants fell under the duties and ties of serfdom , particularly in areas with new patterns of landholding. Between 1066 and 1086, Domesday records a fall in the number of free peasants in Cambridgeshire from 900 to 177, in Bedfordshire from 700 to 90, and in Hertfordshire from 240 to 43. Although not as extreme everywhere, 'English society, in certain areas at least, was a lot less free after the Conquest than it had been before.'

While slavery reduced, many more peasants fell under the duties and ties of serfdom , particularly in areas with new patterns of landholding. Between 1066 and 1086, Domesday records a fall in the number of free peasants in Cambridgeshire from 900 to 177, in Bedfordshire from 700 to 90, and in Hertfordshire from 240 to 43. Although not as extreme everywhere, 'English society, in certain areas at least, was a lot less free after the Conquest than it had been before.'

Thanks to these significant changes to the social structure it has been, wrongly, suggested that William introduced feudalism to England. With no perfectly-functioning feudal system in Normandy, this would have been impossible. But William made use of the apportioning of land to his followers to ensure that rights and expectations were laid out in full. This, Marc Morris argues, was the point of Domesday. When Domesday Book was written, all land was held by William, either directly or as his tenant (or his subtenant), and loyalty and service were expected in return. Domesday therefore established the feudal obligations of William's vassals and thus probably became the only near-perfect example of feudalism working in its truest form. Primogeniture became, at least theoretically, the norm.  Unlike Anglo-Saxon England, where power could be held in many ways, power in Anglo-Norman England was associated with landholding. Estates were not to be divided, leading to the exclusion of women and, problematically, younger sons.

Unlike Anglo-Saxon England, where power could be held in many ways, power in Anglo-Norman England was associated with landholding. Estates were not to be divided, leading to the exclusion of women and, problematically, younger sons.

As the aristocracy changed, so the language of the court was revolutionised. Although it was common sense for Norman migrants to learn some English – William allegedly tried and failed – to manage their tenants and business, in Anglo-Norman England to speak French was to show breeding, status and class. As Robert of Gloucester said: 'For unless a man know French, people regard him little; but the low men hold to English, and to their own speech still.'  French eventually trickled down the social scale: by Hugh Thomas' count, 10,000 French words were adopted into the English language between 1066 and 1485.

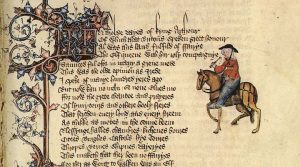

French eventually trickled down the social scale: by Hugh Thomas' count, 10,000 French words were adopted into the English language between 1066 and 1485.  However one only need look at the names for animals – in the field they are sheep, cow and calf, but at the table they are mutton, beef and veal – to see the class differences. Written Anglo-Saxon English didn't disappear overnight. One version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle continued to be written until 1154, and other Anglo-Saxon texts continued to be copied in monasteries. The first writs of William were issued in both Latin and Old English, but as Anglo-Saxon landholders disappeared, so did their language on official documentation. By 1070, no further writs were written in English. It was not until the explosion of literature in the 14th century that written English came back into fashion, and this Middle English would have been as foreign to speakers of Old English as it is to speakers of modern English.

However one only need look at the names for animals – in the field they are sheep, cow and calf, but at the table they are mutton, beef and veal – to see the class differences. Written Anglo-Saxon English didn't disappear overnight. One version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle continued to be written until 1154, and other Anglo-Saxon texts continued to be copied in monasteries. The first writs of William were issued in both Latin and Old English, but as Anglo-Saxon landholders disappeared, so did their language on official documentation. By 1070, no further writs were written in English. It was not until the explosion of literature in the 14th century that written English came back into fashion, and this Middle English would have been as foreign to speakers of Old English as it is to speakers of modern English.

Religion

It might be expected that religion would be one area of continuity, yet in the years following the Conquest religion underwent a reformation. By 1066, with a few exceptions initiated by Edward the Confessor, Pope Gregory VII's reforms had not reached England and it was considered a den of sinners. Afterwards, religion seemed to flourish and William of Malmesbury was convinced that 'The standard of religion, dead everywhere in England, has been raised by their arrival'. 'In 1066 there were around sixty monasteries in England, but by 1135 that number had more than quadrupled to stand at somewhere between 250 and 300; in the Confessor's day, there had been around 1,000 English monks and nuns; by Malmesbury's day there were some four to five times that number.'

Reform was initiated from the top down, with Anglo-Saxon bishops and archbishops replaced by foreigners. In 1068, 10 of England's 15 bishops had been English,  but by the time of William's death, only one English bishop, Wulfstan, remained. Reform wasn't the only driver. In handing out bishoprics, senior clergy became William's vassals and now, unlike in Anglo-Saxon England, the great religious houses owed knight service.

but by the time of William's death, only one English bishop, Wulfstan, remained. Reform wasn't the only driver. In handing out bishoprics, senior clergy became William's vassals and now, unlike in Anglo-Saxon England, the great religious houses owed knight service.

It wasn't merely the top levels of the Church that changed, and just as the Normans questioned the English clergy, so they questioned English saints. Lanfranc, Stigand's replacement as Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote in a letter to his protégé, 'These Englishmen among whom we are living have set up for themselves certain saints whom they revere. But sometimes when I turn over in my mind their own accounts of who they were, I cannot help having doubts about the quality of their sanctity.' Relics, if they weren't stacked away or thrown out completely, were subjected to testing by fire. Further assaults were made on Anglo-Saxon religious practice by the institution of new rituals and language, resulting in the death of three monks, and the injury of a further eighteen, at Glastonbury Abbey.

Relics, if they weren't stacked away or thrown out completely, were subjected to testing by fire. Further assaults were made on Anglo-Saxon religious practice by the institution of new rituals and language, resulting in the death of three monks, and the injury of a further eighteen, at Glastonbury Abbey.

The remaining clergy were taken in hand by the establishment of church courts and councils, overseen by archdeacons . Crimes such as blasphemy were tried in church rather than secular courts. Simony and clerical marriage were banned, with limited results. Episcopal sees were moved from rural areas to urban centres, buildings were cleared and the local peasantry conscripted to construct grand cathedrals. By 1087, nine of England's fifteen cathedrals had been burnt down or demolished to make way for new Romanesque buildings, and the remaining six, along with every major abbey (excluding Westminster) would be rebuilt in the new style subsequently.

Castles

As with cathedrals, the Normans left their mark on the land by building castles. Excluding a few built by Edward the Confessor's French friends, castles were an entirely new and unwelcome addition to the English landscape, a symbol not just of military occupation – and an uneasy one at that – but also of psychological and cultural dominance. At a conservative estimate, by 1100 there were 500 Norman castles in England, including in Exeter, York and Durham – all places which had seen considerable resistance to Norman rule. Some have argued that the castles should be considered more as homes than military fortifications, and some castles – such as Restormel in Cornwall – have architectural features that are hardly sensible in a siege. It is true that they operated as more than mere fortifications – the land was also governed from them, and the great magnates lived, and entertained, in them. Yet they were still a sign of conspicuous consumption, a way of showing the power of the new lord over the populace and over peers. Just as with the rebuilding of cathedrals, castles changed the face of England and that, at least in architectural terms, was revolutionary.

castles were an entirely new and unwelcome addition to the English landscape, a symbol not just of military occupation – and an uneasy one at that – but also of psychological and cultural dominance. At a conservative estimate, by 1100 there were 500 Norman castles in England, including in Exeter, York and Durham – all places which had seen considerable resistance to Norman rule. Some have argued that the castles should be considered more as homes than military fortifications, and some castles – such as Restormel in Cornwall – have architectural features that are hardly sensible in a siege. It is true that they operated as more than mere fortifications – the land was also governed from them, and the great magnates lived, and entertained, in them. Yet they were still a sign of conspicuous consumption, a way of showing the power of the new lord over the populace and over peers. Just as with the rebuilding of cathedrals, castles changed the face of England and that, at least in architectural terms, was revolutionary.

So, can the Conquest be considered a cataclysm? There is no doubt that the Conquest had a significant and long-lasting effect on England. Although the invading Normans were keen to stress continuity, keeping those aspects of Anglo-Saxon England that worked well, society was changed fundamentally. To those experiencing the Conquest, to those who lost their lands, positions, houses, and saints, the invasion was cataclysmic. Over time, as Normans and Anglo-Saxons intermarried, the economy and trade grew, and common enemies gave common purpose, cataclysm turned to assimilation. England's current class structure, language, politics, and landscape are all a result of this process. Given its impact, it's little wonder that Henry of Huntingdon saw fit to write 'God had chosen the Normans to wipe out the English nation'.

Things to think about

- How much of an impact did the Normans have on England?

- Would change have happened in England without the Norman Conquest?

- Did the Norman Conquest represent a cataclysm, or was there more continuity between Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman England?

- Are we still experiencing the effects of the Norman Conquest today?

- How important was the Norman Conquest to the history of England?

Things to do

- The landscape is littered with evidence of Norman occupation. Visit a local castle or cathedral and consider what these buildings tell us about the Conquest: what was their purpose, what do the buildings say about the lifestyle and outlook of the Normans, and how much effort would it have taken to build them?

- Domesday is available online from a number of sources. One of the most detailed and easy to search can be found here.

- Try to write a sentence without using any words introduced to England through the Conquest.

Further reading

An enjoyable and engaging book on the Norman Conquest is Marc Morris' The Norman Conquest. Hugh Thomas' The Norman Conquest: England After William the Conqueror provides a neat, less immediate consideration of the effects of the Conquest on medieval England.