Key facts about the assassination of Julius Caesar

- Julius Caesar was murdered on the Ides of March, 15 March 44 BCE

- His assassins were a number of senators who thought of themselves as 'Liberators'.

- The assassins were worried Caesar wanted to become king.

- His death led to 13 years of civil war and the establishment of the Roman Empire

People you need to know

- Marcus Antonius - commonly known as Mark Antony, was a Roman general and politician, supporter of Julius Caesar, and later a triumvir

- Lucius Minucius Basilus - Roman military commander and senator, and assassin of Caesar.

- Marcus Junius Brutus - descendant of Lucius Junius Brutus (who overthrew Tarquinius) and assassin of Caesar.

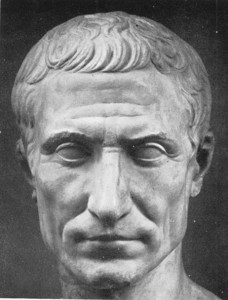

- Gaius Julius Caesar - famous Roman popularis, politician and general, who some feared wanted to be king.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero - Roman orator, lawyer, writer and politician. He may - or may not - have been involved in the plot against Caesar.

- Marcus Aemilius Lepidus - Caesar's Master of Horse and later a triumvir.

- Gaius Cassius Longinus - senator, brother-in-law of Marcus Brutus, and assassin of Caesar

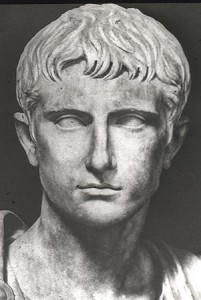

- Octavian - born Gaius Octavius, Octavian was adopted by Caesar in his will, and later became Augustus, the first emperor of Rome.

- Marcus Rubrius Ruga - senator and assassin of Caesar.

- Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix - optimas of Rome. He died in 78 BCE.

- Lucius Tarquinius Superbus - last king of Rome, who was overthrown in 509 BCE.

On the Ides of March 44 BCE, one of the most famous men in history was assassinated. Julius Caesar, general and politician of the people, had risen too far. It was rumoured he wanted to be king and his very existence could ruin the Republic. But ironically, it was the assassination of Julius Caesar that opened the way for Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, to establish an empire.

Reasons for the assassination of Julius Caesar

Rome didn't like kings and ever since Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was overthrown in 509 BCE, it had prided itself on its liberty. To be accused of wanting to be a king was one of the worst insults imaginable. The Late Republic had seen many 'great men', hungry for power and fame, threaten something approaching monarchy, and even within Caesar's lifetime Sulla had marched on Rome, created war and havoc and been named dictator. But Sulla, despite providing Caesar with an example to follow, had stepped down and retired.

We don't know what Caesar's eventual political plans were, nor where he placed himself within them. The position of dictator in Rome was legal and, as Sulla had shown, not particularly unusual in times of emergency. But by 44 BCE, the unusual step was taken of proclaiming Caesar 'dictator in perpetuity'. Opponents worried he was grasping for something more than dictatorship: that he wanted to restore the monarchy, with himself at the head. His behaviour suggested it: he installed his friends in positions of power, started wearing the high red boots traditionally worn by Italian kings, and reacted with fury when a diadem placed on one of his statues was removed. He could wear triumphal dress and the laurel wreath whenever he liked and his statue was placed in all existing temples. Even his admirable trait of granting clemency to opponents could be seen as a reflection of it: to show mercy, one had to be in a position to have power over someone else; one had to be a king.

and his statue was placed in all existing temples. Even his admirable trait of granting clemency to opponents could be seen as a reflection of it: to show mercy, one had to be in a position to have power over someone else; one had to be a king.

Then on 15 February 44 BCE at the Lupercalia, with Caesar wearing a purple toga and golden wreath, he was presented with a crown by Mark Antony. The crowd was unimpressed, Caesar refused, the offer was repeated and again refused. Caesar had made it clear that he did not aim to be king. Or had he? There is much debate over his actions that day, and the intentions behind them. Given Caesar's skill with the crowd, it is unlikely it was done with no reason. Some have suggested it was unplanned, that Antony's exuberance forced Caesar into a corner, although this would seem unlikely. Was it designed to show the crowd that Caesar had no desire to be king, that he never would wear a crown? Or was it perhaps testing the water to see how the crowd would react? Despite Caesar's attempts at reassurance, for the Liberators there was too much risk in letting Caesar live. The risk, of course, wasn't just of political freedom and the health of the Republic, but of the senators' own dignitas.

Or was it perhaps testing the water to see how the crowd would react? Despite Caesar's attempts at reassurance, for the Liberators there was too much risk in letting Caesar live. The risk, of course, wasn't just of political freedom and the health of the Republic, but of the senators' own dignitas. It has been quite rightly argued that the majority of Romans would not have cared whether they were governed by a king or by a senate. Rather, they were interested in stability, peace, and freedom from starvation and oppression. The senators, however, had something to lose.

It has been quite rightly argued that the majority of Romans would not have cared whether they were governed by a king or by a senate. Rather, they were interested in stability, peace, and freedom from starvation and oppression. The senators, however, had something to lose.

The assassination of Julius Caesar

Caesar was rather too relaxed about the danger he'd put himself in. He dismissed his guard of 2,000 men and walked openly through the streets of Rome with only his lictors around him. Perhaps he was trying to show there was no need for Rome to worry, that he was just another man and not a monarch. Perhaps he really thought there was no risk, despite the warnings. In the run up to the Ides of March, Caesar received several warnings of a plot to assassinate him, including from a soothsayer who supposedly said 'Beware the Ides'. Even the nightmares of his wife on the night before his death, which prompted her to beg him not to visit the Senate that day, were not enough to make him rethink. Almost every action and statement he made in the run up to his assassination seemed to be tempting the Fates.

Perhaps he really thought there was no risk, despite the warnings. In the run up to the Ides of March, Caesar received several warnings of a plot to assassinate him, including from a soothsayer who supposedly said 'Beware the Ides'. Even the nightmares of his wife on the night before his death, which prompted her to beg him not to visit the Senate that day, were not enough to make him rethink. Almost every action and statement he made in the run up to his assassination seemed to be tempting the Fates. When his Master of Horse, Lepidus, asked him 'What is the sweetest kind of death?' Caesar replied 'The kind that comes without warning',

When his Master of Horse, Lepidus, asked him 'What is the sweetest kind of death?' Caesar replied 'The kind that comes without warning', and when he saw the same soothsayer on his way to the Senate meeting, Caesar quipped, 'The day which you warned me against is here and I am still alive'. The soothsayer's response was, 'It is here – but it is not yet past.'

and when he saw the same soothsayer on his way to the Senate meeting, Caesar quipped, 'The day which you warned me against is here and I am still alive'. The soothsayer's response was, 'It is here – but it is not yet past.'

Caesar entered the meeting of the Senate by himself, which was taking place at the Curia of Pompey, part of the larger Theatre of Pompey complex. Pretending to take a petition to Caesar the conspirators surrounded him and, at a signal, acted.

which was taking place at the Curia of Pompey, part of the larger Theatre of Pompey complex. Pretending to take a petition to Caesar the conspirators surrounded him and, at a signal, acted.

Cimber caught his toga by both shoulders, then, as Caesar cried 'Why, this is violence!', one of the Cascas stabbed him from one side just below the throat. Caesar caught Casca's arm and ran it through with his stylus, but as he tried to leap to his feet, he was stopped by another wound. When he saw that he was beset on every side by drawn daggers, he muffled his head in his robe, and at the same time drew down its lap to his feet with his left hand, in order to fall more decently, with the lower part of his body also covered. And in this wise he was stabbed 23 times, uttering not a word, but merely a single groan at the first blow, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek: 'You too, my child?' [kai su, teknon]

With so many assassins wildly stabbing at Caesar, many 'found themselves injured by the ancient equivalent of friendly fire.' Cassius cut Brutus's hand and Minucius stabbed Rubrius in the thigh. Those senators who weren't involved in the plot fled into the crowds outside, causing more chaos and confusion. Caesar's body was carried home on a litter by three slaves, with his arm dangling over the side, while his supporter Lepidus went to gather troops - but missed the assassins.

Cassius cut Brutus's hand and Minucius stabbed Rubrius in the thigh. Those senators who weren't involved in the plot fled into the crowds outside, causing more chaos and confusion. Caesar's body was carried home on a litter by three slaves, with his arm dangling over the side, while his supporter Lepidus went to gather troops - but missed the assassins.

Aftermath

Surprisingly little happened to the assassins immediately after Caesar's death. On the evening of the assassination, the 'Liberators' met on the Capitoline Hill, but did nothing to cash in on the confusion. The Senate did not meet and no instructions were issued, as if the assassins were hoping for the restoration of the Republic simply by removing Caesar.

Antony staged a grand funeral for Caesar a few days later. Caesar's popularity was such that a riot developed, leading to Caesar's impromptu cremation in the Forum with wood provided by benches from the law courts. Some of the leading assassins, including Brutus and Cassius, took this as their cue to leave Rome, although neither of them gave up their official positions.

Despite this, for a while the assassins managed to put a positive spin on the events, celebrating it not as a bloody and botched murder, but as an end to tyranny. There was no legal action (as no private prosecutions were brought, and the state – thanks to the Roman legal system – didn't prosecute people). An amnesty was negotiated (through the agreement of the Senate to ratify all of Caesar's decisions) and even a coin was minted, showing two daggers and the pileus, or cap of liberty worn by freed Roman slaves, with the date shown as the Ides of March. It was a celebration of liberty which, as Mary Beard says, resonated with the people like 14 July does in modern France. Cicero even claimed the majority of the people felt sympathy with the assassins, and that the act was viewed as 'the most noble of all illustrious deeds'.

It was not long before Caesar was deified. A bright comet, visible even during the day, appeared in the sky during the games held in his honour, and was a sure sign of the man becoming divine. In January 42 BCE, the Senate agreed Caesar had become a god, an unlikely decision if popular sympathies lay with the assassins.

In January 42 BCE, the Senate agreed Caesar had become a god, an unlikely decision if popular sympathies lay with the assassins.

The assassination of Caesar would have far-reaching consequences for the Roman Republic. It left the 18-year-old Octavian as Caesar's heir and adopted son, providing him eventually with the means and the myth to become Rome's first emperor. The truce did not hold much beyond the arrival of Octavian from the Balkans. Lepidus, Antony and Octavian joined together to form an official Trimvirate, ruthlessly hunting down the Liberators, Caesar's opponents, and personal vendettas. When they ran out of enemies without, they turned on each other. Lepidus was the first to lose to Octavian's scheming, living out his life in exile and obscurity. Antony put up more of a fight, but was finally defeated at the Battle of Actium. He killed himself and died in Cleopatra's arms in August 30 BCE. After decades of civil war, first between Caesar and Pompey and then between Antony and Octavian, anything that provided stability was good. Octavian became Augustus, the first Roman emperor. The foundation of the Roman Empire, as Tom Holland says, was 'the exhaustion of cruelty'. 'Freedom' had been restored and yet the Republic had not.

Things to think about

- What were the assassins of Caesar hoping to achieve?

- Is there anyway the Republic could have been saved?

- Did Caesar want to be king?

- Is there any way Caesar could have avoided assassination?

- Did the assassination of Caesar make the situation better, or worse?

- What was Caesar's relationship to Brutus?

Things to do

- Read what the primary sources have to say about the assassination of Julius Caesar. Two of the easiest to access are by Plutarch and Suetonius.

- For those with the time and resources, visit Rome to see the Area Sacra di Largo Argentina, the closest accessible spot to where Caesar was murdered.

Further reading

No book on Ancient Rome would be complete without an account of the assassination of Caesar. Two of the best, which also provide an excellent overview of the Late Republic, are Tom Holland's Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic and Mary Beard's SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome.

There are plenty of Roman and near-contemporary histories of the assassination of Caesar (as well as of his life). Try Plutarch or Suetonius for a start.