Key facts about Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain

- Caesar invaded Britain in 55 BCE and 54 BCE

- He invaded to stop Britons supporting Gaul during the Gallic Wars, and to enhance his own reputation.

- His invasion was technically illegal, but the Senate granted him 20 days of thanksgiving

- His 55 BCE invasion failed due to bad weather and sea conditions

- In 54 BCE, Caesar was better prepared and managed to cross the River Thames

- Caesar's invasion brought Britain to the attention of Rome

People you need to know

- Alexander the Great - king Alexander III of Macedon, who lived from 356 BCE until 323 BCE and created one of the largest empires of the ancient world.

- Julius Caesar - famous Roman popularis politician and general, who some feared wanted to be king.

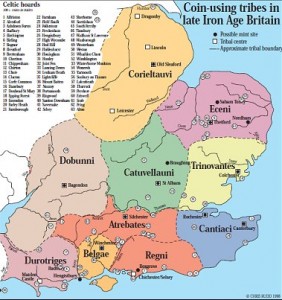

- Cassivellaunus - a British tribal chief who ruled over land north of the River Thames, probably belonging to the Catuvellauni tribe.

- Mandubracius - king of the Trinovantes tribe of south-eastern Britain.

Britain at the time of Caesar's invasion

During the Iron Age Britain was not a single nation but a collection of tribes, perhaps sharing a common language, but with differences in culture and belief. The area inhabited by each tribe shifted over time as political alliances changed and boundaries were disputed, with tribes appearing and disappearing as a result. Although the tribes have been described as warlike, they were also strong traders, both within the island and with the Continent, and there is evidence showing trade links between Britain and Europe since the Bronze Age. British Iron Age culture was an oral one: they did not write down their stories, thoughts or histories. As such, what we know about the tribes comes from archaeology and from outside observers, including Julius Caesar. It is therefore difficult to build a firm picture of them, their history, or their way of life: it is easy for outsiders to be mistaken or confused by different practices, or to misrepresent them deliberately to show British inferiority and outside (Greek or Roman) superiority.

Reasons for Caesar’s invasion

Despite its trade links, the Romans saw Britain, whose 'sky is obscured by continual rain and cloud',  as on the edge of the known world, and at first glance it would seem an unlikely target for their aggression. There was unrest in Rome, and trouble in its provinces and along its borders, so surely the Romans had enough to be doing. What then motivated Caesar to pick an illegal fight with an island so far removed from civilisation? Firstly, and importantly in the eyes of the average Roman, Caesar claimed it was self defence. He invaded Britain to protect Rome. As he said in his Gallic Wars, 'He made this decision because he found that the British had been aiding the enemy in almost all our wars with the Gauls'.

as on the edge of the known world, and at first glance it would seem an unlikely target for their aggression. There was unrest in Rome, and trouble in its provinces and along its borders, so surely the Romans had enough to be doing. What then motivated Caesar to pick an illegal fight with an island so far removed from civilisation? Firstly, and importantly in the eyes of the average Roman, Caesar claimed it was self defence. He invaded Britain to protect Rome. As he said in his Gallic Wars, 'He made this decision because he found that the British had been aiding the enemy in almost all our wars with the Gauls'.  With trading and cultural connections between Gaul and south-eastern Britain, it was natural for Britain to support Gaulish resistance, and if the Britons were offering aid to the enemy, Caesar wasn't starting a new war, but pursuing victory over Gaul.

With trading and cultural connections between Gaul and south-eastern Britain, it was natural for Britain to support Gaulish resistance, and if the Britons were offering aid to the enemy, Caesar wasn't starting a new war, but pursuing victory over Gaul.

Despite their need to justify war, Rome was a state that survived on conquest. It needed the spoils of war (in taxes, slaves, and other items) to keep it functioning. By the Late Republic, the city of Rome was not self-sufficient, and was constantly under pressure from its increasing size. The plebeian masses could be terrifying: imports of cheap wheat and other foodstuffs were required to keep them from starving and rioting, and the legions demanded payment, in cash or in land. Conquered territories could provide both.

There were also personal reasons for Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain. He had no doubt heard about the riches in the British Isles, known for the 'gold and silver and other metals',  that the Britons had traded with the Continent for centuries. In the Late Republic, the spoils of war were shared between the state, the conquering generals, and - to a lesser extent - their soldiers, and Caesar, as a politician who knew how to gamble and had racked up significant debts in his climb to the top, needed the money.

that the Britons had traded with the Continent for centuries. In the Late Republic, the spoils of war were shared between the state, the conquering generals, and - to a lesser extent - their soldiers, and Caesar, as a politician who knew how to gamble and had racked up significant debts in his climb to the top, needed the money. But more than money, he needed power and publicity.

But more than money, he needed power and publicity.  Greatness in Rome was measured by great deeds, judged against those of the ancestors and other men, and Caesar wanted to be great. Plutarch reports that:

Greatness in Rome was measured by great deeds, judged against those of the ancestors and other men, and Caesar wanted to be great. Plutarch reports that:

When free from business in Spain, after reading some part of the history of Alexander, he sat a great while very thoughtful, and at last burst out into tears. His friends were surprised, and asked him the reason of it. "Do you think," said he, "I have not just cause to weep, when I consider that Alexander at my age had conquered so many nations, and I have all this time done nothing that is memorable."

There were other, more pressing, reasons for the invasion. Having already acted in a legally questionable manner during his consulship,  Caesar was aware that once he returned to Rome he could be prosecuted, and he had enough enemies to make him nervous of the outcome.

Caesar was aware that once he returned to Rome he could be prosecuted, and he had enough enemies to make him nervous of the outcome.  The successful invasion of somewhere so distant, so barbaric, and yet so rich would not only win him further popularity with the people, it would also make his case in the Senate stronger. It might even allow him a further extension as governor, delaying any hopes his enemies might have of prosecuting him. But the British campaign was also politically dangerous, as he would be campaigning outside the territory assigned to him, and in crossing the Channel he was making one of his well-placed political gambles.

The successful invasion of somewhere so distant, so barbaric, and yet so rich would not only win him further popularity with the people, it would also make his case in the Senate stronger. It might even allow him a further extension as governor, delaying any hopes his enemies might have of prosecuting him. But the British campaign was also politically dangerous, as he would be campaigning outside the territory assigned to him, and in crossing the Channel he was making one of his well-placed political gambles.

55 BCE: Caesar's first invasion

Caesar intended to cross to Britain in 56 BCE, but was delayed first by a Gaulish rebellion in modern-day Brittany and the area around Calais, and then by German incursions across the Rhine.  Strabo claimed the Gaulish uprisings were a deliberate attempt to disrupt the invasion of Britain, as it was in the Gauls' interest to delay it and forewarn the British tribes. Furthermore, Gaulish traders refused to provide any useful intelligence on Britain to Caesar, beyond hazy details about coastal areas and that portion of the island immediately opposite Gaul.

Strabo claimed the Gaulish uprisings were a deliberate attempt to disrupt the invasion of Britain, as it was in the Gauls' interest to delay it and forewarn the British tribes. Furthermore, Gaulish traders refused to provide any useful intelligence on Britain to Caesar, beyond hazy details about coastal areas and that portion of the island immediately opposite Gaul.  Caesar complained that:

Caesar complained that:

He could not learn from them the size of the island, or how many people or nations inhabited it, or what system of warfare they practised, or what customs they followed, or where harbours might be located suitable for a big fleet of large ships.

Thanks to the warnings from the Gauls, the British tribes were well-prepared when Caesar's first fleet of eighty transport ships, carrying two legions,  entered British waters.

entered British waters.  The defenders stood at the cliff tops and, for a while, succeeded in holding off the Romans with slings and darts. The Romans, harassed and concerned about leaping fully armoured into deep water, were unwilling to meet the enemy. They lingered on board until the standard bearer of the tenth legion jumped off the boat shouting 'Leap, fellow soldiers, unless you wish to betray your eagle to the enemy. I, for my part, will perform my duty to the Republic and my general'. Shamed, the rest of the legionaries followed and the two armies met in the shallows in chaos and confusion.

The defenders stood at the cliff tops and, for a while, succeeded in holding off the Romans with slings and darts. The Romans, harassed and concerned about leaping fully armoured into deep water, were unwilling to meet the enemy. They lingered on board until the standard bearer of the tenth legion jumped off the boat shouting 'Leap, fellow soldiers, unless you wish to betray your eagle to the enemy. I, for my part, will perform my duty to the Republic and my general'. Shamed, the rest of the legionaries followed and the two armies met in the shallows in chaos and confusion.

The fighting seemed to go the way of the Britons, until Caesar ordered shallower-bottomed ships to carry more troops to dry land, at which point the tribes turned and fled. They were not pursued far: the Romans had no cavalry. Following this defeat, representatives of the British tribes sued for peace, promising payment of a tribute and providing hostages.

It had not been Caesar's plan to invade without cavalry, and 18 transport ships had been arranged to carry them, but when

they were approaching Britain and were seen from the camp, so great a storm suddenly arose that none of them could maintain their course at sea; and some were taken back to the same port from which they had started;-others, to their great danger, were driven to the lower part of the island, nearer to the west; which, however, after having cast anchor, as they were getting filled with water, put out to sea through necessity in a stormy night, and made for the continent.

The Romans, up until this point, had been used to the calm waters of the Mediterranean, which provided a stark contrast to the choppy waters of the Channel. The sudden arrival of the storm would have seemed almost magical to the Romans, or a sign of an unhappy god.  The bad weather and rough sea didn't just affect the cavalry transports. Water filled the infantry transport and warships, and the sea sent them crashing together, wrecking many. Those that did survive were not fit for sailing.

The bad weather and rough sea didn't just affect the cavalry transports. Water filled the infantry transport and warships, and the sea sent them crashing together, wrecking many. Those that did survive were not fit for sailing.

Despite their initial 'victory' the Romans were stranded on their beachhead without provisions or resources for repairing their only means back to Gaul. The British tribes seized their chance, employing guerrilla tactics and attacking foraging parties. The situation quickly turned to stalemate: the Britons could not match the Romans in open battle, and couldn't retake the beach, but nor could the Romans move beyond it. Ambassadors were again sent to Caesar, promising fresh tribute and hostages, but Caesar, needing to return to the Continent before winter, asked for them to be sent after him. Caesar, his ships once again seaworthy, departed soon afterwards and was granted 20 days of thanksgiving by the Senate, an unusual honour and one which encouraged him to return the following year.

The 54 BCE invasion

When Caesar did return, it was with a greater and improved invasion force adapted from the lessons he'd learnt the previous year.  After an uncontested landing, Caesar continued through Kent. He met British tribes probably somewhere on the River Stour, but pushed them back to a hillfort, where they scattered. Unwilling to push his luck with night falling in unknown territory he made camp, only to find that his fleet had again suffered from bad weather. Forty ships at anchor in the Channel had been wrecked and others damaged by a storm and high tides. A temporary return to the coast was needed, where he sent word for more ships and his men spent 10 days and nights repairing those they could.

After an uncontested landing, Caesar continued through Kent. He met British tribes probably somewhere on the River Stour, but pushed them back to a hillfort, where they scattered. Unwilling to push his luck with night falling in unknown territory he made camp, only to find that his fleet had again suffered from bad weather. Forty ships at anchor in the Channel had been wrecked and others damaged by a storm and high tides. A temporary return to the coast was needed, where he sent word for more ships and his men spent 10 days and nights repairing those they could.

When Caesar returned to the Stour, he found the tribes had used the time to organise their resistance under Cassivellaunus, a powerful warrior king of (probably) the Catuvellauni tribe.  After a few skirmishes, Cassivellaunus realised he couldn't defeat the Romans in pitched battle and again resorted to guerrilla tactics. He used chariots and superior knowledge of the territory to delay the Roman army on their march north, giving the British time to fortify the only fordable place on the River Thames. The British use of chariots was enough to frighten the Romans and impress Caesar, who described their tactics in the Gallic Wars:

After a few skirmishes, Cassivellaunus realised he couldn't defeat the Romans in pitched battle and again resorted to guerrilla tactics. He used chariots and superior knowledge of the territory to delay the Roman army on their march north, giving the British time to fortify the only fordable place on the River Thames. The British use of chariots was enough to frighten the Romans and impress Caesar, who described their tactics in the Gallic Wars:

First they drive in all directions hurling spears. Generally they succeed in throwing the ranks of their opponents into confusion just with the terror caused by their galloping horses and the din of the wheels. They make their way through the squadrons of their own cavalry, then jump down from their chariots and fight on foot. Meanwhile, the chariot drivers withdraw a little way from the fighting and position the chariots in such a way that if their masters are hard-pressed by the enemy’s numbers, they have an easy means of retreat to their own lines. Thus, when they fight they have the mobility of cavalry and the staying power of infantry: and with daily training and practice they have become so efficient that even on steep slopes they can control their horses at full gallop, check and turn them in a moment, run along the pole, stand on the yoke, and get back into the chariot with incredible speed.

The fortification of the Thames was not enough to prevent the Romans crossing it. One second century Macedonian author, Polyaenus, suggests that Caesar used an elephant to scare away the tribes. Caesar himself makes no reference to an elephant, merely stating that 'the soldiers advanced with such speed and such ardour...that the enemy could not sustain the attack of the legions and of the horse, and quitted the banks, and committed themselves to flight'. The point was proved, though: the tribes fought best in small numbers using the land to their advantage, and open battle should be avoided.

British tribal life was fraught with internal conflicts and rivalries. Cassivellaunus had recently conquered the Trinovantes, in what is now Essex, forcing their prince, Mandubracius, into exile. Mandubracius, sensing a powerful potential ally in Caesar, approached Caesar and agreed a peace in return for his restoration to the Trinovantes under the protection of Rome.  The Trinovantes would send 40 hostages to Rome and grain for the army, as well as providing much needed information. Five other tribes,

The Trinovantes would send 40 hostages to Rome and grain for the army, as well as providing much needed information. Five other tribes,  seeing the protection given to the Trinovantes against violence and pillage, followed suit, also providing provisions and information, including the location of Cassivellaunus' stronghold. A siege was laid and, after a diversionary attack on the Roman's beachhead failed, Cassivellaunus surrendered.

seeing the protection given to the Trinovantes against violence and pillage, followed suit, also providing provisions and information, including the location of Cassivellaunus' stronghold. A siege was laid and, after a diversionary attack on the Roman's beachhead failed, Cassivellaunus surrendered.

With trouble brewing on the Gaulish front, Caesar left without fulfilling the conquest (if he ever meant to), but with treasure and treaties from a few tribal chiefs, as well as the British hostages. Caesar's acknowledged reason for the invasion, to prevent the Britons from helping the Gauls, succeeded: there is no further reference to the British fighting in their defence.

The legacy of Caesar's invasion

Caesar’s immediate effect on Britain was little, but he brought the island to the attention of Rome and into her sphere of influence. The south east of Britain, at the very least, developed closer ties with the Roman world. Trade between Britain and Rome increased, and children of the elite were educated in Rome, enhancing the tribes' Romanitas, or Romanisation.  Rome now had a political investment in Britain: the Trinovantes were technically left as a protectorate,

Rome now had a political investment in Britain: the Trinovantes were technically left as a protectorate,  while Rome became a refuge for other exiled tribal leaders,

while Rome became a refuge for other exiled tribal leaders,  and Strabo tells us that a number of British chieftains paid homage to Augustus following the civil war. UnRoman Britain argues there was also military investment in the island, with evidence for Roman troops being posted in the client lands of Britain before the Claudian invasion of 43 CE. Whether these troops were there to protect the interests of clients, to intimidate, to prepare for a more formal incursion, or for a combination of reasons cannot be known. Julius Caesar's invasion made it possible, 100 years later, for a tribal chief to appeal to Rome for help, and for the Roman Empire to seize that excuse for the full-scale invasion and annexation of Britain.

and Strabo tells us that a number of British chieftains paid homage to Augustus following the civil war. UnRoman Britain argues there was also military investment in the island, with evidence for Roman troops being posted in the client lands of Britain before the Claudian invasion of 43 CE. Whether these troops were there to protect the interests of clients, to intimidate, to prepare for a more formal incursion, or for a combination of reasons cannot be known. Julius Caesar's invasion made it possible, 100 years later, for a tribal chief to appeal to Rome for help, and for the Roman Empire to seize that excuse for the full-scale invasion and annexation of Britain.

Things to think about

- Was it wise of Caesar to invade?

- Did the Gauls want to help Britain fight Caesar?

- What does his invasion tell us about Caesar as a man and a general?

- What does Caesar's invasion tell us about the health of the Late Roman Republic?

- What effect did Caesar's invasion have on Britain?

Things to do

- Although there is no archaeological evidence for Caesar's landing in Britain, he is believed to have landed on either Deal or Walmer beach in Kent. There is a memorial stone at Walmer beach which you can visit. Whilst there, look around and see how easy - or difficult - it would have been to land an invasion force there.

Further reading

For those wanting to understand Rome during the Late Republic, Tom Holland's Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic provides a good introduction. Caesar's Gallic Wars, books four and five are an extremely important source for understanding Caesar's invasion of Britain. There are a number of translations available for free on the internet (such as this one), including in Latin for the brave, or you can buy it from Amazon.