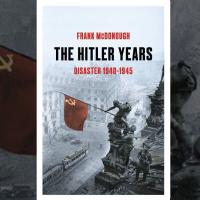

The Hitler Years: Disaster, 1940-1945 is the eagerly awaited second volume in Frank McDonough’s new and extensive history of the Third Reich. Immediately following on from The Hitler Years: Triumph, this new volume charts the final peak of Nazi Germany’s successes in 1940 and early 1941 – the diplomatic gains, the huge military advances across the continent and the numerous crushing defeats of the Allies, all of which increased the government’s popularity at home – before documenting its catastrophic fall into chaos and absolute military and political defeat in 1945.

A book of this sort, covering a period of – to a greater or lesser extent – ‘total’ war necessarily focuses heavily on military campaigns. McDonough makes no bones about this, carefully narrating and analysing each major battle and the turning points they represented. As the book makes clear, it is important to understand the central place that war held within Nazi Germany and Hitler’s ideology: lebensraum, the search for living space for the German volk, could only be achieved through conquest. But it is equally important to understand that this space was to be achieved through expansion eastwards, taking lands from the ‘racially inferior’ – and therefore ‘unworthy’ – Slavic nations. So more than simply a volume of military history, McDonough’s The Hitler Years: Disaster provides insight into the German nation, its politics, and its mindset. Studying the regime at war and the way it fought on the different fronts neatly illustrates the racial and ideological motivation, not just of Hitler, but of the people, generals and common soldiery, that drove military strategy. Hitler’s diplomatic ability, flexibility, even his mental and physical health, are mapped against success and failure during the war, while the atrocities committed by the regime are shown as a reaction to the particular circumstances created by it.

This concentration on war and genocide runs the risk of making any book on the subject a heavy and depressing read. Yet there are flashes of literary genius from McDonough that, while perhaps not making the book ‘enjoyable’, do make it engaging. This is not to say that McDonough makes light of the Nazi regime – his abhorrence for Hitler’s ideology is clear – but his approach is nuanced, subtle, and mature. It is exceedingly difficult for a historian of the Third Reich to take a balanced, ‘objective’ approach to the subject matter – after all, Hitler was ‘evil’, and the Allies were fighting a ‘just’ war – but McDonough achieves this and, in doing so, unpacks each myth in turn in a thoroughly convincing, well-evidenced manner. Criticism in the main is implicit: McDonough’s use of documentary and photographic primary sources does much of the leg work, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions. McDonough’s choice of case studies, the aspects he explains in detail and those that he merely mentions, highlights the ironies and complexities of the period, encouraging readers to think for themselves and challenge any number of notions that, in the past eighty years, have become something akin to modern foundation myths. Nor is McDonough’s approach reserved just for those living within the Third Reich: very few of the major players, Allied or Axis, come out of the book with an unblemished record. The reader can’t help but compare Hitler’s concern for the Parthenon and Athenian architecture favourably against the deliberate Allied bombardment of the ancient Benedictine abbey at Monte Cassino, while details of the plight of civilians in Dresden, Hamburg, and a multitude of other German cities leave an acrid taste in the mouth. In this manner, McDonough takes on the huge weight of historiography – and the politics behind it – in a masterful way.

Given the scope of the book, it is hardly surprising that one – in fact possibly the only – complaint might be that some aspects are given more attention than others. More space could, perhaps, have been devoted to the German massacres of Italian prisoners of war in Greece for example, but it is nearly impossible to condense satisfactorily so many elements, each warranting libraries of books themselves, into a mere two volumes. Instead, what McDonough has done, and done well, is to select his narrative strands – for the second volume, particularly the war against the Soviet Union, the collaboration of those within and without Germany, and the escalation of the persecution of Jews and other ‘untermenschen’ – to create a narrative that is coherent and convincing, while allowing the reader to pursue other aspects through a comprehensive bibliography and notes. Thus, McDonough is practising the craft of the historian at the highest level.

The Hitler Years: Disaster and its companion volume, The Hitler Years: Triumph, are not just informative on a nearly encyclopaedic level, they are well-researched, well-structured, and well-written. What’s more, they are relevant and challenging. Through questioning the myths that still exist, they encourage the reader to think in a new way, not just about the past, but about the present and the future. The Hitler years weren’t just an aberration caused by the fanaticism of one man, but were a set of ideas actively supported by many in the army, the judiciary, big business, and society at large. And nor was ‘right’ always on the side of the Allies, who fought the war for a number of economic and political reasons, and who afterwards turned a blind eye to the many war criminals who were left to retreat into obscurity. These two thought-provoking volumes, given the information they contain and the arguments they make, are, therefore, more than worthy of a place in the Hitler canon. They will be used for years to come as the essential starting point for any study of the Third Reich.