Throughout the history of cinema, writers, directors and producers have searched for dramatic, engaging stories to capture the attention of audiences. Sometimes these have been creations of their authors, stories that claim no connection with real world events or previously released works. Of course, there is a strong argument that no story is 'original', in that all tales are created by people whose experiences of life and the world have shaped their thinking and opinions. Therefore, nothing can be truly detached from reality. Frequently however, film-makers have turned to previously created works of fiction to form the basis of their productions.

The problem is, film is a different medium, arguably with a different aim and a different target audience. It is therefore natural that film producers have had to rework the stories to better suit the alternative medium. Stories can be restructured, characters changed or removed, events in the plot re-imagined. It is common for film-makers to come in for criticism of this kind of adaptation, primarily from fans of the original works. It makes sense. Beloved characters have been altered and parts of the book which spoke to a particular reader in an important way may have been altered beyond recognition. Still, the filmmaker has to make this judgement call. Peter Jackson made the decision to remove the famous character of Tom Bombadil from The Lord of the Rings, and for good reason. The Bombadil section in the novel would have seriously slowed the pacing of the film, adding nothing to the overall story which had to be told in a far shorter space of time.

Yet if a director tackling a much-loved novel runs the risk of criticism for changes made, the one who tackles the minefield that is historical cinema is brave indeed. History provides a rich source of stories that can be even more powerful for an audience because of their basis in real world events. The difficulty here comes with the nature of historical research itself. Historians frequently disagree on why events in history took place, and even on what actually happened. The further back we go, the harder it is to find sources of reliable information and so personal interpretation by the historian is inevitable, if not essential. When a filmmaker comes to deal with historical events, they need to condense huge numbers of ideas, characters, events, actions and motivations into an engaging piece of entertainment. If the professionals cannot even agree what went on and spend their lives writing books on the topic thick enough to fell an elephant, what hope does the filmmaker have?

And so, inevitably, historical cinema comes in for endless criticism from reviewers, viewers and – of course – historians for 'artistic licence' when it comes to translating the past to screen. This is not always unreasonable. One reason for criticism is that, as with historians themselves, filmmakers bring their own interests, opinions and biases to their work. They make films not just to entertain, but generally speaking to express a message. This can often lead to dramatic changes in the personalities and motivations of characters, particularly as there is a need to make some of them relatable, so as to allow the audience an emotional anchor. It can also mean that some perspectives are missed – or deliberately ignored – to assert the director's message and vision. In many cases, one simply would not want to use a film as a means of teaching or learning history. Indeed, perhaps the biggest downside of films claiming historical truth as their basis is the fact that people might take away the idea that they are indeed watching something that truly happened. It is entirely possible that people might come away from Mel Gibson's mind-blowingly obnoxious Braveheart believing that William Wallace actually knocked up Isabella of France and fathered the future Edward III – regardless of the fact that Isabella was a toddler at the time of Wallace's capture. Audiences 'enjoying' U571 might actually leave the cinema with the idea that American sailors, including Jon Bon Jovi, had managed to lay their hands on the first captured Enigma encoding device, when in actual fact the film is based on actions by British sailors before the United States had entered the war. People viewing Pearl Harbour may come away with the idea that the assault on the American fleet was less interesting than drying paint. Films that for the most part sail closer to the shores of historical accuracy carry this danger to perhaps an even greater extent. One thinks of the daft scene near the end of Darkest Hour where Winston Churchill takes the longest single-stop journey in the history of the London Underground so as to have a rousing natter with The People.

So then what value is there in an historical film, especially one which takes huge liberties with accepted ideas and 'truths'? Actually, quite a lot, if we can suppress our academic snobbery and outrage and get some perspective.

The first benefit of historical cinema is that, while it may miss out the complexity of the events, a film can still give both a broad view of historical events and introduce characters from the past to engage viewers and give them some sort of basic grounding – in Stateside parlance, a 'History 101'. Audiences can be exposed to places, times, events and people of whom they may have had little or no awareness prior to seeing the film. Any opening and expansion of the mind is a precious thing, regardless of inaccuracies or narrowness inherent in a cinematic rendering of past events. This raising of awareness brings us to the most important and valuable aspect of even the most historically-bananas film.

Inspiration. Inspiration to learn.

How many people first found themselves drawn to the study of Ancient Rome after watching Ridley Scott's Gladiator? How many found themselves hungry for more information about, and experience of, the world in which they had found themselves enveloped over the duration of that historically playful classic of modern, big-budget entertainment? How many people wanted to learn more about Scottish history after getting through Braveheart? How many wanted to know more about Edward I? The film's Longshanks was a scenery-chewing, sneering, baby-munching, sadistic scumbag. The man himself, while not exactly likeable, was far more interesting, and if anybody came out of watching Gibson's exercise in putting history into a food processor wanting to find out more, that made it all worth it. It is the power of film, with all its emotionally manipulative artifice and attention-grabbing sensationalism that pulls a person into a new world. And if that world happens to have been based on the real one, many will wish to delve deeper.

Two examples that have led me to new areas of reading and study: Ridley Scott's Kingdom of Heaven and Ronald F. Maxwell's Gettysburg.

Kingdom of Heaven is out of this world in its freewheeling disregard for historical accuracy. Orlando Bloom's Balian of Ibelin is decades younger than his real world counterpart at the time of the events depicted in the film. His origin story is completely inaccurate. The marvellous Brendan Gleeson's Reynald de Châtillon is a wacky caricature based solely on traditional representations of the man, is (SPOILER ALERT) captured by his fellow Christians rather than Muslims and imprisoned for about five minutes, rather than a decade and a half as in reality. He is shown as a member of the Templars, which he was not. If Jeremy Irons's Tiberias is supposed to be Raymond III of Tripoli as seems to be suggested, no mention is made of his alliance with Saladin that enabled the leader of the Muslim army to freely stomp across the turncoat's lands into the Crusader States. The chronology of events is muddled around for dramatic effect. All the good guys spend their time making thoroughly modern statements about the similarities between themselves and Muslims and about how greater understanding is required.

However, the film is still able to introduce the world and peoples of Outremer and Syria in the twelfth century to those who have never bothered to look into it. It looks amazing, as do all of Scott's films, regardless of their quality otherwise. It is dramatic and thrilling, with a stellar cast and entertaining performances. Prior to watching the film, I had never studied the Crusades or the states which were created in the Levant, my interests and reading always having been focused elsewhere. My interest was fired and I delved into book after book on the subject, enthralled by the stories and fascinated by the different analyses of the characters and events in books by different writers.

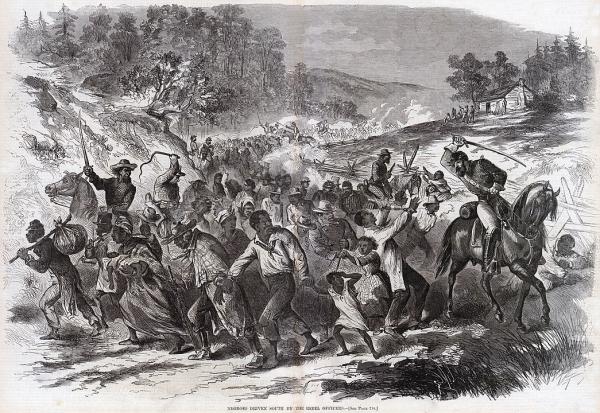

More recently, the re-viewing of Gettysburg – a film which gives the battle it depicts a run for its money in terms of duration – fired a new interest. Ignorant to a truly embarrassing degree of the ins and outs of the American Civil War, the film highlighted these personal deficiencies and demanded action. Yet this film has caught a lot of flack for its social and political message and way of dealing with the events it portrays. Branded as 'bloated Southern propaganda' by Gene Siskel, its biased portrayal of the Confederate soldiers and their ideas about the Cause were obvious even to this ignorant viewer. Every five minutes Southerners would opine that their fight had nothing to do with slavery and everything to do with freedom and defence of their rights. The portrayal of Robert E. Lee, in spite of a fine performance by Martin Sheen and an acknowledgement of his errors was borderline hagiographic. There was a lot of chivalric behaviour on both sides and a seemingly endless series of meaningful speeches about ideology and beliefs.

Yet the film had a great effect. Its length worked in its favour in allowing the battle and its structure to really be portrayed and broken down in an engaging manner. Its fine performances, from Sheen, Tom Berenger and the exceptional Jeff Daniels introduced me to some fascinating characters about whom I wished to know a lot more. Even the cinematic approach which pushed emotional manipulation to an extreme, with triumphant, soaring music every time a battle took place, regardless of who was doing the fighting, and everybody getting a final 'it's been an honour, sir' farewell as they were dying, pulled me in, in spite of myself. The glory charge of the 20th Maine at Little Round Top gave me shivers. I wanted more. A lot more. Weeks have now been spent pouring over books and immersing myself in all the perspectives and information I can find. This all being said, I seriously advise avoiding the sequel, Gods and Generals. It takes the Southern angle to an extreme level and does not justify its four-and-a-half-hour runtime and features one of the worst child performances this side of The Goonies.

Regardless, let nobody tell you that inaccurate or questionable historical cinema is a waste of time or a worthless means of learning about the past. The power of cinema is and has always been the power of presenting something enthralling. History is enthralling. When combined, the two cannot help but inspire.

Things to Do

- Pick a popular historical film, the more mainstream the better. Watch it, enjoy it, but do not trust it. Then read, read and read.

Main image by Bart from New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.