Tackling the Mythology of the Arctic Convoys

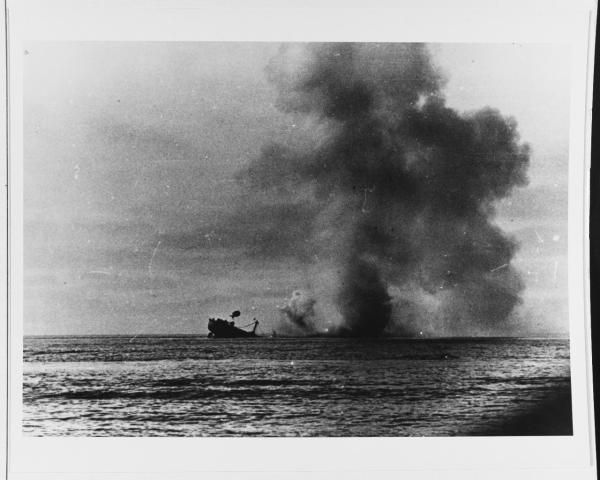

Winston Churchill, who during the Second World WarA global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945. served both as First Lord of the Admiralty as well as prime minister, famously remarked in his history of the war, ‘The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril’. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, 6 vols (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985), vol. ii, p. 529. With the desperate need to keep supply lines open for both armaments and food, it's hardly surprising that a convoy disaster, such as that of PQ-17 in July 1942, was considered to be ‘one of the most melancholy naval episodes in the whole of the war’.

Winston Churchill, The Second World War, 6 vols (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985), vol. ii, p. 529. With the desperate need to keep supply lines open for both armaments and food, it's hardly surprising that a convoy disaster, such as that of PQ-17 in July 1942, was considered to be ‘one of the most melancholy naval episodes in the whole of the war’. Ibid., vol. iv, p.237.

Ibid., vol. iv, p.237.

The experience of the merchant sailors involved in the Arctic convoys is also widely viewed as one of the worst of all those involved in the Second World War at sea. Each journey was a battle against the elements: stormy seas, and extreme cold, with the added burden of waiting constantly for the sudden shock of a torpedo hitting a nearby ship, or worse still your own, and sentencing you to a perhaps mercifully quick death in the freezing waters. Part of the perceived horror comes from the lack of agency these men had in their own fates, forced simply to hold station in the convoys and await events. Typically the story is framed as one of defenceless merchant ships, constantly at the mercy of omnipotent U-boat ‘wolfpacks’ hunting them down, while under the meagre protection of Royal Navy corvettes and other small escort vessels. These stories make for stirring reading and have an important place in the historiographyThe study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. of the war, but they do not necessarily reflect the real events.

Churchill was keen, in 1940 and 1941 to emphasize the threat to the UK for the benefit of public and political opinion in the United States. This was done in order to gain as much help as he could from his neutral trading partner across the Atlantic, and ultimately bring them into the war on the side of the Empire. Later, once the Arctic convoys began in the summer of 1941, Churchill was engaged in an equivalent propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. campaign directed at Stalin and the Soviet UnionThe Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or Soviet Union, was a Marxist-Leninist state covering much of eastern Europe, Russia and Asia between 1922 and 1991.: only by emphasising the effort and cost of the Arctic convoys could he counter the Russian leader’s incessant calls for a second front on mainland Europe and more help to defeat Germany. The result of these efforts was to frame the convoys both as critical to the ability of the UK to continue the war against Germany, but also as a fight where the enemy held many of the strategic and tactical advantages. This framing was necessary to wartime politics but has also cast its shadow over the way the campaigns have been viewed in popular memory.

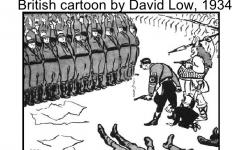

A contribution to this mythology was also made by the Nazi regime itself, which lauded its submarine captains and their crews on the same level as ace fighter pilots and offered them up in the media as icons of national prowess. Historian Michael Hadley, in his study of just this phenomenon remarked: ‘During both wars, and during the interwar years as well, the U-boat was mythologized more than any other weapon of war.’ Michael Hadley, Count Not the Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995), p.1. This point was reiterated by Clay Blair in his seminal two-volume history Hitler’s U-Boat War as follows:

Michael Hadley, Count Not the Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995), p.1. This point was reiterated by Clay Blair in his seminal two-volume history Hitler’s U-Boat War as follows:

The myth goes something like this: the Germans invented the submarine (or U-boat) and have consistently built the best submarines in the world. Endowed with a canny gift for exploiting the marvellously complex and lethal weapons system, valorous (or alternatively, murderous) German submariners dominated the seas in both world wars and very nearly defeated the Allies in each case.

Clay Blair, Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters, 1939-1942 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996), p. xi.

Recent scholarship, however, has questioned these legends. It is now widely acknowledged that the threat of British defeat by the U-boats was probably never as severe as Churchill claimed. Also far from being invulnerable hunters, the German submarines became increasing prey to Allied ships and aircraft equipped with sophisticated anti-submarine technology including ASDIC (sonar), Radar, depth charges and homing torpedoes. To quote Blair again:

Contrary to the accepted wisdom or mythology ... U-boats never even came close at any time to cutting the vital north Atlantic lifeline to the British Isles.

Clay Blair, Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunted, 1942-1945 (New York: Modern Library, 1998), p. 707.

It is not the intention here to suggest that the convoy battles in either the Atlantic or the Arctic were insignificant, or indeed a foregone conclusion. On the contrary, the reverse is the case: these battles have a much richer, more complex and nuanced history that has been recognized hitherto by the mainstream narratives. The old ‘U-boat vs merchant ship and escort’ narrativeA story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. is no longer sufficient to describe these events.

A significant layer of detail has also been missing from the popular accounts of the campaign in the Arctic. This is the role of wireless interception and signals intelligence (SIGINT), exploited by both sides during the campaign, a story which remained highly secret until the late 1970s and has remained often unacknowledged since. Central to this story is the Naval Section of the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, whose break into German naval Enigma in 1941 came at a crucial time for the defence of the Arctic convoys. A section which started with five people and four chairs, grew into an intelligence generating machine employing over five hundred people. Thousands of messages were successfully delivered to the Admiralty revealing vast quantities of detail on the German navy’s movements and intentions. How that intelligence was used or not used, and the consequences in terms of ships sunk and lives lost, lie at the heart of this story.

Throughout the campaign a significant proportion of German U-boat wireless traffic was successfully intercepted and decrypted by the Allies. The constant communication that was maintained within U-boat groups, and with their shore-based controllers meant that the Admiralty nearly always had some warning of where patrol lines were being formed across the path of the convoys, and how many boats were involved. Long-term analysis of traffic also allowed the Admiralty to keep a good understanding of the size of the enemy submarine fleet, its losses and state of readiness, and its current doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. and tactics. In addition to the U-boat fleet, signals intelligence was also able to provide a thorough strategic understanding of the air picture. This was derived from naval sigint but also the prolific and more easily broken LuftwaffeGerman term for the air force, which means 'air weapon'. wireless networks. The Admiralty was kept regularly informed of the scale of the air threat and the make-up of the enemy striking forces and their base locations. An area of Luftwaffe activity which also produced a significant SIGINT dividend to the Allies was interception of communications to and from reconnaissance aircraft. The sighting reports that these aircraft provided, and the homing signals that shadowing aircraft provided for U-boats meant that both Bletchley Park and units afloat often had a good indication of whether or not the enemy knew the whereabouts of a convoy, and if and when contact was lost. This was an asset to commanders both at sea and on shore.

Perhaps most significant of all, however was the window provided by SIGINT on the movements and intentions of the German surface navy. In the end, the surface units of the KriegsmarineNazi Germany's navy. had a minimal material effect on the Arctic convoys, sinking only three merchant ships in the whole campaign. Their effect on the Royal Navy was more significant: a series of set-piece battles were fought between the two navies in the Arctic, with the cruisers HMS Edinburgh, and Trinidad, the destroyer Achates and the minesweeper Bramble all lost as a result of combat with German surface ships. Significant damage was also inflicted on other warships in these engagements. However, the importance of the German surface units, and in particular their capital ships, lay more in their potential for destruction, and the strangle-hold this placed on Allied operations until the final destruction of Tirpitz in November 1944. The possibility of a sortie by a German surface task force had to be taken into account in the planning of each convoy, and a substantial part of the Home Fleet, including its principal battleships as well as its often sole fleet aircraft carrier, were required to sail as covering forces each time a convoy cycle was undertaken. This placed a huge strain on Royal Navy resources. The British heavy units also required their own escorts, further depleting the force of destroyers available for close escort of the convoys themselves. The hard-pressed RN cruiser squadrons were also called upon to accompany many of the convoys, and it was this branch of the service that did much of the surface fighting and took the greatest losses.

It was in these surface operations that SIGINT was perhaps at its most useful, both strategically and tactically. At the long-term level ULTRA and its supporting intelligence sources (coast watchers and air reconnaissance) were able to keep close tabs on the locations of the German heavy units, and their state of readiness for sea. The monitoring of the cycles of damage to, and repair of, Tirpitz are a case in point. The ship was tracked from the moment it left its slips in 1938 until it capsized in 1944. There was rarely a moment when the Admiralty did not have a good idea where it was, or at least where it had recently been. The story is the same for the other capital ships including Scharnhorst, as well as the cruiser and destroyer squadrons. Part of the reason for this was the vice-like grip that German naval high command insisted on keeping over its Norwegian assets. Wireless traffic approving every movement of these vessels, as well as ancillary messages arranging minesweeper and air cover for their activities meant that there was plentiful SIGINT available whenever any activity by the German surface fleet was in prospect. Equally, and arguably crucially in the case of Tirpitz and PQ-17, the absence of this ancillary W/TWireless Telegraphy/Telephony activity was also good indicator of the state of German operations. When an operation by the heavy units was planned, prior information was often also available concerning the nature of those plans. In this regard the intelligence provided by Swedish interception of German land-line communications provided a vital advantage, occasionally giving chapter-and-verse of the German plans.

There is little doubt that in human and material terms the Kriegsmarine came off worse in the Arctic campaign compared with the Royal Navy and the merchant ships it escorted. The fact also remains that more than 90 per cent of the tonnage of goods supplied to the Soviets, and the ships in which it was carried, arrived safely. Sceptics both at the time and since 1945 have questioned whether the continuation of convoys to Russia was a rational or worthwhile operation of war. In terms of the ‘Safe and Timely Arrival’ of the merchant shipping, which was so often cited as the Navy’s primary purpose, the campaign was broadly a success. Official Historian Stephen Roskill summed this up:

The balance of success therefore plainly lay very much on the Allied side; and as the Royal Navy conducted all the operations, and provided almost all the escorts, that service may feel justifiably proud of an achievement as great as any recorded in its long history.

Stephen Roskill, The War at Sea, 1939-1945 (London: HMSO, 1961), vol. 3.2., p.262.

Writing in 1961, Roskill was not able to disclose the role SIGINT played in the campaign as these matters would remain secret for another 15 years. However there is little question that the Allied SIGINT operation, from the ‘Y’ interceptors ashore and afloat, via the codebreakers of Hut 8 at Bletchley Park, the analysts of Naval Section or the plotters in the Operational Intelligence Centre, made a significant contribution to the success of the overall campaign. Contrary to the prevailing mythology, not only did the Allies and the Royal Navy win the campaign in the Arctic, but they did so with the help of a huge and previously largely unacknowledged signals intelligence effort, at the heart of which lay the codebreakers of Bletchley Park.

David Kenyon's new book, Arctic Convoys: Bletchley Park and the War for the Seas, published by Yale University Press is available to buy now.

Cover image © IWM A 15421

- Log in to post comments