Forged in Ice and Fire: The Tale of the Polish II Corps

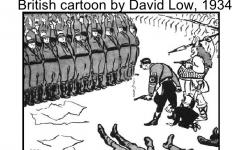

1939 was not a good year for Poland. September saw it invaded and conquered by two of the most repellent regimes ever to have sullied the Earth with their presence. Just over two weeks after finding its western border assaulted by the forces of Nazi Germany, Poland found itself fighting a war on two fronts as the Soviet UnionThe Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or Soviet Union, was a Marxist-Leninist state covering much of eastern Europe, Russia and Asia between 1922 and 1991. piled in from the east. Courageous defence by the armed forces and the unrealised promise of support from its British and French allies was never going to be enough. In early October the fight to hold the wolves at bay was over and the country was torn into three pieces. Yet the war was not over.

The Ends of the Earth

The people of Poland suffered greatly at the hands of their new occupiers. Far off in Moscow, the Soviet leaders had plans for Poland that would not allow for any form of resistance. Suspected threats – military officers, intellectuals, politicians and many others – were loaded aboard trains, frequently with their families, and deported in their thousands to the distant and remote hell of the Soviet gulags. Many others simply disappeared. Those 'lucky' enough not to disappear remained in the gulags with little hope of survival, let alone freedom. Conditions were harsh, rations and medical care meagre, treatment brutal. If the Nazis treated the Poles atrociously, the Soviets were no better. In total, well over a million Poles found themselves forced from their homeland to the faraway Soviet wastes, a land of ice stretching to the distant horizon, and had little hope of ever being set free. Huge numbers were sent to mines, where they worked in horrific conditions and died in huge numbers. At one mine in Kolyma, as many as 11 workers died each day as a result of vicious treatment, starvation and the cold. Certainly the secret services were following the instructions of the Politburo in Moscow to 'beat the Poles for all you are worth'. Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps (London: Allen Lane, 2003) p.142.

Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps (London: Allen Lane, 2003) p.142.

And then, in 1941, things changed. Emboldened by the swift German victories in the West, frustrated with the stalemateWhere neither opponent can make a move or win. after the Battle of Britain, and driven by his anti-Jewish, anti-Soviet mania, Adolf Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the full-scale invasion of the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin, watching matters unfold from Moscow, had a serious problem. While the potential military capacity of the Soviet Union may have been vast, its equipment and materiel were at that time outmoded and not up to the task of pushing back the better-equipped and better-trained German forces. To compound the issue, Stalin had managed to hobble the Red Army by having huge numbers of its experienced officers killed or deported during his pre-war purges. He continued to 'liquidate' generals as each defeat occurred.

Stalin needed soldiers. A lot of them. And he knew where he could find some. In a fairly obnoxious about face, without a hint of contrition, he set 'free' a huge number of the Polish gulag inmates for the purpose of forming a Polish army in the Soviet Union. It is doubtful many of them were particularly grateful to Moscow's Politburo, but freedom from the gulags and a chance to fight again for their beleaguered nation was a great opportunity.

The Commander

The operation to free the Polish prisoners and form the new force was not carried out in a particularly systematic or organized way. A lot of would-be soldiers found themselves on their own, making their way to where they hoped their compatriots would be assembling. While initially this was in the Soviet Union, when the NKVD (the USSR's sinister and repressive security force) began interfering more and more with the creation of the army, the Western Allies decided it would be better to get the Poles out of the country entirely. The rendezvous point was then moved to Persia (Iran), outside the sphere of Moscow's direct influence. Tens of thousands of Poles made their way south to join up and – if possible – find friends and families they had lost. One man was tasked with turning these malnourished and mistreated refugees into a fighting force.

Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders had also suffered greatly at the hands of the Soviets. Wounded in the final days of the Polish struggle, he was arrested and imprisoned by the NKVD. Forced from interrogation to interrogation, kicked repeatedly down flights of stairs when his wounded leg and crutches made him move too slowly for his guards, he nevertheless maintained his great personal dignity. Dedicated only to forming the army and fighting for a free Poland, he cooperated with Soviet leaders, yet one thing that continually concerned him was the inexplicable absence of many officers who were known to have been captured by Soviet forces in 1939. Forming an effective new army without experienced officers would be a far harder task. Although he confronted the Soviets repeatedly regarding this issue, he was given either dismissive explanations for the disappearances or assurances that the officers would turn up, without much being done to locate them.

Of course, it is now very well known what had happened to the officers. Not long after their capture, they were executed in their thousands and dumped in mass graves alongside many of their compatriots. The most famous instance was the Katyn Massacre, yet the same thing took place in many locations. Back in 1941, Anders had no idea what had happened, so he continued to build as best he could. Thousands and thousands of Poles made their way to the Middle East to join up and fight.

There were a great number of dedicated men and women who joined the cause, but one in particular was really quite special.

Smarter than the Average

Private Wojtek had first joined the II Corps as the army made its way through Iraq, travelling to British Palestine. When he was first found he was in a terrible state. He was eventually taken in by the 2nd Transport Company, which would later become an artilleryLarge guns used in warfare, or referring to the group that uses those guns. supply unit. Although he had never served in an army, he was enlisted as Private, to allow him to receive army rations to sustain him and build up his strength and also to get around British Army regulations which forbade certain participants from being transported on troop ships. In many ways, similar experiences could be found throughout the Polish II Corps, but Wojtek was certainly a special kind of soldier.

He was a bear.

Wojtek travelled with the II Corps for the rest of the war, a fine mascot for the unit and a source of much amusement for both the soldiers and visiting commanders and generals. He picked up strange habits from his comrades, not least a fondness for the consumption of cigarettes and alcohol. When the army was transferred to Italy, Wojtek would, in many ways, become more than a mascot. He would do his part too.

Show Me the Way to Monte Cassino

The most famous of the II Corp's achievements came in 1944, in the mountains of Italy on the road to Rome. The town of Cassino sat below Monte Cassino, a hill topped with the first Benedictine monastery. For months and months the Allies had tried in vain to punch through and displace the German forces holding the area. The German positioning and fortifications, combined with the forbidding topography had led to the loss of thousands of lives as the armies of various nations had fought for control. After three devastating assaults, a fourth, and hopefully final, attack was planned, and the II Corps was to be critical in carrying it out.

Anders was keen to have II Corps involved, regardless of any reservations he might have had about the attack and the likelihood of yet another costly battle. He saw it as a chance for the Poles not only to prove their worth in combat, but to finally put to bed the Soviet lie that they had no interest or willingness to take on German forces. This was to be the moment of truth for Anders, and the whole II Corps – an opportunity to display their great resolve and dignity, and a chance for immortality.

Naturally, they would not be alone in the attack. Four armies were set to fight in different areas. The Americans and the Free French would make their way around the German positions, in an attempt to draw forces from elsewhere. In the valleys around Cassino itself, the British Army would move in the centre right while the Poles would attack from the right.

The attack was launched on the evening of 11 May, with a terrifying and awesome display of firepower. Sixteen-hundred artillery guns lit up the night, blasting the town and hill of Cassino for forty minutes straight. Just over an hour later, the Poles began their climb. Soon the hillside was a scene of the most terrible carnage, soldiers trapped under relentless fire on slopes that had been left with no cover at all after months of bombardment. The Poles were unable to move in great numbers. Instead, small groups of German and Polish soldiers would fight their own miniature battles, taking and then losing areas of ground without any let up.

It was not just soldiers fighting the desperate fight. Armoured units too were making their way through the firestorm. Polish sappers would move in front, removing landmines so progress could be made, all the while under fire. Many would actually crawl beneath the tanks themselves for cover, before darting out, removing a mine and then diving back beneath the metal beasts for cover. Such staggering bravery slowly but surely allowed the Poles to move forward, although always fighting against being forced into retreat.

Further back, the 22nd Artillery Supply Company was hard at work, desperately moving ammunition to the guns so firing could continue. With them was that remarkable bear Wojtek, no longer afraid of the thundering guns, moving among the men. It was then that he pulled off his most famous feat. Copying the actions of his comrades, Wojtek began to lift and move the ammunition as well, so the legend goes. Back and forth the men went, and so did their mascot. So amazing was the story that the company later incorporated Wojtek into its emblemA heraldic device or symbol that forms the badge of a nation, organisation, or family., an artillery shell under his arm.

Finally, on the morning of 18 May, after a week of slaughter, the Polish Carpathian Division's 12th Poldolski Lancers entered the monastery atop Monte Cassino, raising first their regimental colours, then the Polish flag, then a Union Jack out of respect for their British comrades. Monte Cassino had been taken, but at a terrible price. In his memoirs, Anders recorded the number of soldiers lost as 72 officers and 788 of all other ranks. More than one hundred men were missing and nearly three thousand had been injured. Władysław Anders, An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps (London: MacMillan, 1949), p. 181. And it was not over. Through the rest of 1944 and into 1945, the II Corps made its way north, taking Ancona alongside their allies and fighting almost without rest. They suffered hundreds more casualties, including 38 killed and 180 injured in a tragic friendly-fire incident in which a rifle division was mistakenly bombed by the American Air Force.

Władysław Anders, An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps (London: MacMillan, 1949), p. 181. And it was not over. Through the rest of 1944 and into 1945, the II Corps made its way north, taking Ancona alongside their allies and fighting almost without rest. They suffered hundreds more casualties, including 38 killed and 180 injured in a tragic friendly-fire incident in which a rifle division was mistakenly bombed by the American Air Force. Kenneth K. Koskodan, No Greater AllyA state (or person) that is formally working with another state (or person), usually confirmed by a treaty or other official agreement.: The Untold Story of Poland's Forces in World War II (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2011) p.135.

Kenneth K. Koskodan, No Greater AllyA state (or person) that is formally working with another state (or person), usually confirmed by a treaty or other official agreement.: The Untold Story of Poland's Forces in World War II (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2011) p.135.

By the time the Germans surrendered and the war in Europe ended, the Polish II Corps had distinguished itself through its bravery, efficiency and determination, and won the respect of its allies.

And then...

When the war ended for most European countries, it did not end for the Poles. Agreements made between the leaders of the three main Allies – the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain – at conferences in Tehran and Yalta had left Stalin in control of almost all the Polish territory the Soviet Union had captured in 1939. The much-reduced Poland that remained was ultimately to be ruled by a pro-Moscow puppet government and had lost its independence.

For Poles who had fought hard to retake their fractured nation, it was a damning blow, made more painful for being a betrayal by their allies. For Anders, as for tens of thousands of other Poles who had served across Europe in the fight against Nazi Germany, there was no real possibility of returning home. The Soviet Union was a terror state. Anders had already been captured, tortured and accused of crimes against the 'International Proletariat' by the NKVD in 1939. He certainly could not have gone home, if he had even wanted to. The same was true for thousands in the Polish II Corps who had already experienced incarceration in distant gulags.

The communistSomeone who believes in the ideals of communism, where property is owned collectively and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs. Polish government took away Anders' citizenship and, like so many of his comrades-in-arms, he became part of a huge Polish diaspora which spread around the world. He settled in London, where he lived until his death in 1970. As per his wishes, he now lies alongside his fellow soldiers in the Polish War Cemetery at Monte Cassino.

Wojtek had a happier life after the war. He spent much of it at Edinburgh Zoo, where people would still come and see him, chucking him cigarettes. He finally died in 1963.

It has taken a long time for the endeavours of forces like the Polish II Corps to make their way back into the global consciousness. There is still a long way to go until both the heroism and betrayal are fully appreciated, but small gestures and steps forward are happening. Wojtek is commemorated in a statue in Edinburgh and has even been the star of a children's book.

More poignantly and meaningfully, in 2021 a bust of Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders was unveiled at the National Army Museum in London. Beside it is a plaque bearing the title 'Our Polish Allies'. It tells the story, in brief, of the remarkable, resilient and courageous people who made up the Polish II Corps, from their suffering in Russia, through their journey to Tehran, to the mountains of Italy. Their sacrifice was great. Their endeavours were even greater.

Things to think about

- What more can be done to highlight the role of the Polish in the Second World WarA global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945.?

- What were the similarities and differences in the way the Nazis and the USSR treated Poland; what does this say about the respective regimes?

- Were the western Allies right to cede the majority of Poland to the USSR, and did they have any other option?

- What is the place of animals in war, and is it a good thing?

- Is there any place for conservation of culture and history in war, and were the Allies correct to destroy Monte Cassino?

- Is there, or should there be, a collective sense of guilt about how Poland was treated during and after the Second World War?

Things to do

- The Imperial War Museum houses a permanent collection focusing on the Second World War, and some exhibits reference the contribution made by Poland. It also has an extensive, although currently chaotically arranged, collection of photographs about the Polish II Corps.

- The National Army Museum in London houses the new bust of Władysław Anders, along with a range of relevant collections.

- It is possible to visit both the abbey of Monte Cassino and the Polish war cemetery at Cassino, Lazio, in Italy.

Things to Read

For a look at the experiences of Polish military and underground forces during the war, a good start is Kenneth K. Koskodan's No Greater Ally. It covers each area of Polish involvement in some detail and has a very easy, readable style.

For a detailed and very readable look at the whole of the Battle of Monte Cassino, Monte Cassino: Ten Armies in Hell by Peter Caddick-Adams is definitely the best choice.

Wojtek the Bear is the subject of Aileen Orr's enjoyable Wojtek the Bear: Polish War Hero, looking quite a bit at his life after the war. For younger readers, The Bear Who Went to War by Alan Pollock and Bryony Thomson is a great introduction to the story.

Anybody who wants to learn more about the history and horrors of the Soviet gulags would do well to read Anne Applebaum's Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps.

Finally, although it is currently out of print and hard to access, An Army in Exile is the memoir of Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders himself. Written a short time after the end of the war, it is moving, fascinating and a valuable resource.

Title image: © IWM HU 128077

- Log in to post comments