Amundsen’s Last Expedition

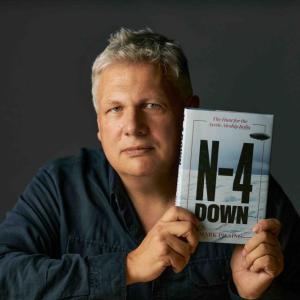

Guest article by Mark Piesing

Shortly after 4pm on 18 June 1928, the flying boat carrying the great polar explorer Roald Amundsen on his last expedition was seen by a Norwegian fisherman flying over the Arctic ocean into 'a bank of fog that rose up over the horizon…and disappeared before our eyes' – and it was never seen again. Stephen R. Brown, The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen (Boston, MA: De Capo Press, 2012), p. 322.

Stephen R. Brown, The Last Viking: The Life of Roald Amundsen (Boston, MA: De Capo Press, 2012), p. 322.

The Roald Amundsen that most people know is the ruthless polar explorer, the first to sail through the Northwest Passage in 1905 and who beat Scott to the South Pole in 1911. A man nicknamed 'the Governor' because he brooked no dissentAn opinion or belief that goes against official teaching or commonly held views.. Tor Bomann-Larsen, Roald Amundsen (Cheltenham: History Press, 2011), Chap 4, Kindle. An explorer at the peak of his game.

Tor Bomann-Larsen, Roald Amundsen (Cheltenham: History Press, 2011), Chap 4, Kindle. An explorer at the peak of his game.

The Roald Amundsen most people haven’t heard of is the troubled aviation pioneer. The polar explorer-turned-aeronaut who liked to boast that in the early flights of pioneers such as the Wright Brothers he had seen the potential of aircraft to end the long, tedious forced march of the explorer. The man who experimented with man-lifting flying kites – then cutting-edge technology – in 1909; made his first flight in San Francisco in 1913; started flying lessons the following year; and was awarded Norway’s first civilian pilot’s licence in 1915.

Nor do most people know that Amundsen made three attempts to fly to the North Pole in the early 1920s, which ended variously in failure, public humiliation, personal bankruptcy, and depression. Four years that Amundsen described as 'the most distressing, the most humiliating and altogether tragic episode of my life' – and left him 'depressed', in a room in New York’s Waldorf Astoria in 1924, watching creditors’ final demands being pushed under his door. Brown, p. 18; Roald Amundsen, My Life As An Explorer (New York: DoubleDay, 1927), p. 119, reprinted by Forgotten Books.

Brown, p. 18; Roald Amundsen, My Life As An Explorer (New York: DoubleDay, 1927), p. 119, reprinted by Forgotten Books.

This was a very public ordeal that ended only when Amundsen received a phone call from Lincoln Ellsworth, the son of a leading American industrialist, offering to fund his expeditions; a call that would eventually lead to him returning, with Ellsworth, to the Arctic in May 1925 for one more attempt to fly to the North Pole.

And nor do people know that Amundsen disappeared three years later, in June 1928, flying to join the search for Italian aeronaut Umberto Nobile and other survivors of the airship Italia, which had crashed a month earlier near the North Pole.

The train of events that led to Amundsen’s last expedition began three years earlier on 21 May 1925, when two state-of-the-art Dornier Wal flying boats took off from the frozen waters of Kings Bay, Svalbard, for the eight-hour, 500-mile flight to the North Pole. Amundsen and Ellsworth were soon crossing a 'desolate and deserted' landscape that would have taken weeks to do with skis and dogs. 'Expeditions: The N24/ N25 Flight Towards The North Pole (1925)', Fram Polar Exploration Museum [accessed 20 March 2021].

'Expeditions: The N24/ N25 Flight Towards The North Pole (1925)', Fram Polar Exploration Museum [accessed 20 March 2021].

But once again, Amundsen’s attempt ended in disaster when they crash-landed 100 miles from the North Pole, the men in 'the kingdom of death' facing carving a take-off strip for the surviving aircraft out of the drifting sea ice before their food ran out. Lincoln Ellsworth, 'Arctic Flying Experiences By Airplane and Airship', Problems of Polar Research, American Geographical Society Special Publication, 7 (1929), p. 415.

Lincoln Ellsworth, 'Arctic Flying Experiences By Airplane and Airship', Problems of Polar Research, American Geographical Society Special Publication, 7 (1929), p. 415.

After three and a half weeks and six take-off attempts, their fuel all but gone, they landed on the sea close to Svalbard. This time Amundsen was greeted as a hero, and he was sure of three things: he was going back to the Arctic; he was going to need an airship; and there was only one man who had an airship available – Italian engineer and aviator Umberto Nobile.

The only problem was that to buy it Amundsen would have to do-a-deal with the dictatorA ruler with total power over a country. of Fascist Italy, Benito Mussolini, who wanted to use the polar flight for propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. purposes.

The Norwegian was obsessed with flying to the North Pole really for one reason: what lay beyond it. Largely forgotten today, maps in the 1920s had a large, shaded area on the other side of the North Pole from Europe usually labelled simply 'unexplored region'. Called the last great hole in the map, it was believed to contain undiscovered land, rich in oil and other minerals; and it was the perfect location for the airfields needed to open the transpolar air route and to control the Arctic skies. For the Governor, it would be a suitable final triumph for his career, and the publicity caused by its discovery offered the promise of one last big paycheque.

It may seem a ridiculous idea to us today that Amundsen wanted to return to the Arctic in an airship, but in the 1920s airships were widely seen as the future of aviation, or a future. Compared to aeroplanes, they could fly for far longer and carry more supplies, and offered a stable platform for navigation and scientific research.

However, Amundsen had a problem: time. He was running out of it. The Governor had tried to get to the North Pole in 1922, 1923, 1924 and 1925 when he faced little or no competition, and on each occasion, he had failed. Now The New York Times announced that 'MASSED ATTACK ON POLAR REGION BEGINS SOON … Ten Expeditions Will Probably Go into the Frozen North This Summer … Explorers Hope to Find a New Continent.' 'Massed Attack on Polar Regions Begins Soon', The New York Times, Sunday, 7 March 1926.

'Massed Attack on Polar Regions Begins Soon', The New York Times, Sunday, 7 March 1926.

In May 1926, Amundsen, Ellsworth, and Nobile – with the support of Mussolini – joined multiple engineers and explorers in the race to be the first to fly to the North Pole, in what Science Monthly called 'the most sensational sporting event in human history'. Cited in Brown, p. 286. It was a competition that Amundsen and his partners won. On 14 May, the airship Norge, designed, built, and piloted by Umberto Nobile, landed in Teller, having taken off from Svalbard on the other side of the North Pole 71 hours earlier.

Cited in Brown, p. 286. It was a competition that Amundsen and his partners won. On 14 May, the airship Norge, designed, built, and piloted by Umberto Nobile, landed in Teller, having taken off from Svalbard on the other side of the North Pole 71 hours earlier.

The Norge flight over the North Pole was a global event, a stunning success, and it was described as the one of the greatest achievements of the twentieth century. It took up three and a half pages of The New York Times. But the tensions that had been building before and during the flight exploded after it.

Amundsen had believed that Nobile was to be the equivalent of a hired driver, but the Italian wouldn’t accept that role. He had renegotiated his salary, demanded that he write one chapter of the lucrative book of the expedition, and insisted that the expedition name be changed to Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile.

This was too much for Amundsen, who accused him of repeatedly panicking while in command and of attempting to take credit for the expedition. That Nobile was called by Americans the 'New Columbus' really didn’t help his mood either. W. T. Whitlock, 'Cleveland Airport Ohio', Aviation Week, 10 August 1926.

W. T. Whitlock, 'Cleveland Airport Ohio', Aviation Week, 10 August 1926.

Tragically, what Amundsen hadn’t understood was that aeronauts like Nobile had replaced the explorer as the public’s aspirational heroes. They were the astronauts of their day. Neither did he appreciate how Mussolini was able to mobilize the Italian diaspora via the Fascist League of North America to make sure Nobile was greeted as the hero everywhere he went in the United States.

Amundsen retired back to his beloved home in Uranienborg, Norway, where he swung between depression at how the last expedition of his career had turned out and fury at how Nobile and Mussolini had stolen the credit for it.

By contrast, Umberto Nobile had decided almost the moment they touched down in Alaska to return to the Arctic in a new airship. Stung by Amundsen’s public criticisms of him, Nobile wanted to show that the Italians could explore the Arctic by air without the Norwegian’s help, and he named this airship the Italia.

'We are quite aware that our venture is difficult and dangerous – even more so than that of 1926 – but it is this very difficulty and danger which attracts us', said Nobile on the eve of his departure from Italy. 'Had it been safe and easy other people would have already preceded us'. Umberto Nobile, With the Italia to the North Pole (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1930), p. 82.

Umberto Nobile, With the Italia to the North Pole (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1930), p. 82.

Nobile’s flight in the Italia back to the North Pole should have been the easiest out of the five flights he planned in the summer of 1928, but it turned into the deadliest. In the early morning of 25 May, the Italia crashed on to the ice, in terrible weather. With the gondola ripped off, the envelope of the airship floated away, leaving nine men on the sea ice – including a severely injured Nobile – and six still on board, who were never seen again. The only clue to their fate was a pillar of smoke on the horizon.

Like in a Marvel movie, the next day many of the world’s top explorers, including Roald Amundsen, were gathered at the Dronningen Restaurant in Oslo, when a telegram boy rushed in with a message from Svalbard. It was bad news: the Italia had not returned from its flight to the North Pole.

The mood of the dinner turned dark. What had happened to the airship? Where could it have crashed? How would the Italians cope on the ice floe?

A few minutes later the explorers were instructed to go straight to the defence ministry to plan a mission to look for Nobile and the crew of the Italia.

The room went quiet. Everyone looked at Amundsen. 'There was no diner there who didn’t remember the bitter public quarrel between the two men'. Wilbur Cross, Disaster at the Pole: The Crash of the Airship Italia (Lanham, MD: The Lyons Press, 2000), p. 127.

Wilbur Cross, Disaster at the Pole: The Crash of the Airship Italia (Lanham, MD: The Lyons Press, 2000), p. 127.

The great explorer’s reply was simple: 'Tell them at once that I am ready.' Cited in Cross, p. 127.

Cited in Cross, p. 127.

Why did Amundsen agree to help Nobile? There were the rules of honour that Amundsen fully understood. There was the glory. Becoming the leader of the international effort to rescue the crew of the Italia would be a worthy end to Amundsen’s career. Perhaps Amundsen would be able to forgive Nobile for stealing the credit for the flight of the Norge if he could have the delicious final victory of grasping Nobile’s hand and pulling the Italian off the ice.

Or perhaps there was a darker motive. Amundsen didn’t expect – or want – to return from such a mission. He had heart problems and recently had been treated for cancer in Los Angeles, which may explain his recent decisions to settle his debts and give away some of his most prized possessions to friends.

What we do know is that the conversation took a dark turn when Amundsen was interviewed by journalist Davide Giudici in early June 1928. He pointed at a model of the kind of flying boat in which he had tried to reach the North Pole three years earlier. 'If only you knew how splendid it was up there!' he exclaimed. 'That’s where I want to die, and I wish only that death will come to me chivalrously, will overtake me in the fulfilment of a high mission, quickly and without suffering.' Cited in Davide Giudici, The Tragedy of the Italia (Boston, MA: D. Appleton and Company, 1929), 29-30.

Cited in Davide Giudici, The Tragedy of the Italia (Boston, MA: D. Appleton and Company, 1929), 29-30.

Unfortunately for Amundsen, Mussolini had the final word over who would lead the mission to find Nobile, and Il Duce didn’t want the Norwegian. Side-lined, he had to watch as his former right-hand man Riiser-Larsen become its de factoA Latin phrase meaning 'in fact', but not necessarily in law. leader.

Soon it seemed like the whole world wanted to rescue Nobile and his men. In all, 23 planes and 20 ships from Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Norway, the Soviet UnionThe Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or Soviet Union, was a Marxist-Leninist state covering much of eastern Europe, Russia and Asia between 1922 and 1991., Sweden, and the United States would be thrown into the desperate search to rescue the survivors.

Now Amundsen was under pressure. The press may have praised him for wanting to come to the aid of a man he hated, but this praise would turn into derision if he didn’t do something soon.

His solution was to launch his own independent rescue mission. But his reputation wasn’t what it had been. In the end, the French government agreed to supply a flying boat and provide a crew led by Captain René Guilbaud – one of their best pilots – and Lincoln Ellsworth would fund it. But the Latham wasn’t the state-of-the-art machine the Dornier Wal had been. Yes, it was a new French design built for transatlantic flights, but its wood–metal hull meant that it couldn’t land on the ice, and, underpowered, it needed a large stretch of open water to land safely. So, if Amundsen found the survivors the Latham could not land to rescue them. The best he could do would be a flyby to drop supplies. If that wasn’t bad enough, the Latham 47 itself was only the second of its type constructed, and a fire had destroyed the first (never a good omen).

But it was easy for Amundsen to push these worries to one side for now. For it was 16 June 1928. Nobile and his men had been stranded on the sea ice for three weeks, and Amundsen was only just now on the train leaving Oslo to rendezvous with his French plane at Bergen and fly up to Tromsø for the jump to Svalbard.

It was also 25 years, almost to the day, that he set sail on the expedition to discover the Northwest Passage – which he had done – and now, hundreds of people were on the platform to see him leave on this new mission.

Early in the morning of 18 June Amundsen’s Latham 47 arrived in Tromsø harbour, after completing the 758-mile flight from Bergen. To his friend Fritz G. Zapffe, Amundsen seemed distant, as if there was something between them that the explorer could not share, and Zapffe would later interpret Amundsen’s mood as a premonition of his death. Perhaps the limitations of the design of the Latham for Arctic exploration that seemed theoretical in France were reality in Tromsø. He certainly complained about the machine to Zapffe – and wished he was flying a Dornier Wal instead. He even gave his friend his lighter to keep. He had taken it on every expedition, but Amundsen told Zapffe: 'I will have no more use of it.' Cited in Tor Bomann-Larsen, Chap 47. He was reluctant to pose for the cameras while getting on the plane. He looked like a man resigned to his fate.

Cited in Tor Bomann-Larsen, Chap 47. He was reluctant to pose for the cameras while getting on the plane. He looked like a man resigned to his fate.

Despite his unease about the plane, Amundsen turned down suggestions from the Swedish and Finnish pilots to wait till the next day so they could all fly together for safety.

So, at 4pm, 18 June, the Latham, with Amundsen, René Guilbaud and four others on board, taxied across the water at Tromsø. It appeared to onlookers to be too heavy, perhaps even overloaded. The engines of the underpowered prototype design roared, and as it raced across the calm water of the harbour, it was clear it was struggling to take off. But at last the plane ascended. It was going to be a nerve-racking seven-hour flight to Kings Bay.

Later, the fisherman who saw the Latham flying into the cloudbank told journalists, '[T]he machine began to climb presumably to fly over it but then it seemed to me she began to move unevenly.' Cited in Brown, p. 322. It is well known that flying in fog causes disorientation and loss of spatial awareness.

Cited in Brown, p. 322. It is well known that flying in fog causes disorientation and loss of spatial awareness.

Two radio messages were received from the Latham. At 6pm, when it had been in the air for two hours: 'Nothing to report.' And then, just after 7pm, the mysterious 'Do not stop listening. Message forthcoming.' Karen May and George Lewis, 'The Deaths of Roald Amundsen and the Crew of the Latham 47', Polar Record 51 (2015), p. 5.

Karen May and George Lewis, 'The Deaths of Roald Amundsen and the Crew of the Latham 47', Polar Record 51 (2015), p. 5.

Whatever that message was, the operator didn’t have time to send it. A coal ship on its way up to Kings Bay later reported hearing a faint SOS. It is possible that these were the last distress calls ever to be heard from Amundsen and the Latham.

Now the search for Amundsen began to gain momentum, taking away many of the aircraft and boats deployed to search for Umberto Nobile and the survivors of the Italia. The difficulty was that no one really knew whether they were looking in the right place or not. It was a case of dropping a pin in the rather large hole in the map.

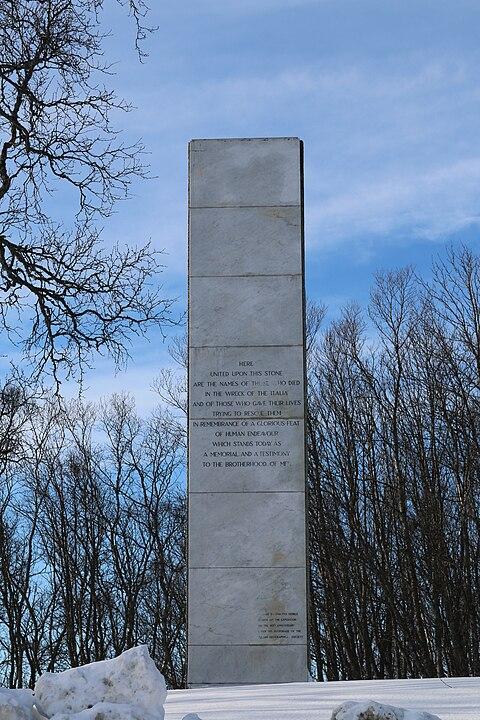

It seemed wrong to many Norwegians that Amundsen had disappeared but that Nobile was found alive four days later, on 22 May. On 16 July, the day the Norwegians gave up the hunt for Amundsen, the survivors of the Italia landed at the Norwegian port of Narvick, to be met by hundreds of Norwegians standing on the quayside in silence, and local newspapers calling for 'Death to Nobile'. Steiner Ass, 'New Perspectives on the Italia Tragedy and Umberto Nobile', Polar Research 24 (2005), p. 7.

Steiner Ass, 'New Perspectives on the Italia Tragedy and Umberto Nobile', Polar Research 24 (2005), p. 7.

Only three confirmed pieces of Amundsen’s plane have ever been recovered. One of the wing floats of the Latham was recovered from the sea later in the summer; the struts and wires were still attached to it, indicating it had been torn off the plane. A fuel tank was found near Trondheim, Norway, that same year; another a year after.

The fate of Roald Amundsen and the Latham may never be known. Plenty of wreckage was found that could have been from Amundsen’s plane but couldn’t be confirmed as such, and even some that might have been deliberate fraud, as well as many sightings of the plane, and Amundsen, alive, as far away as Mexico.

The hunt for Roald Amundsen continues to this day. In 2012, underwater drones were employed to sweep the seafloor for wreckage of the Latham, to no avail. It may be that his fate will be finally revealed only by the melting sea ice.

Click here to buy Mark Piesing's N-4 Down, which tells the full story of the hunt for the Italia.

Cover image: © Preus Museum Anders Beer Wilse.

- Log in to post comments